Love, Fiercely

Loading...

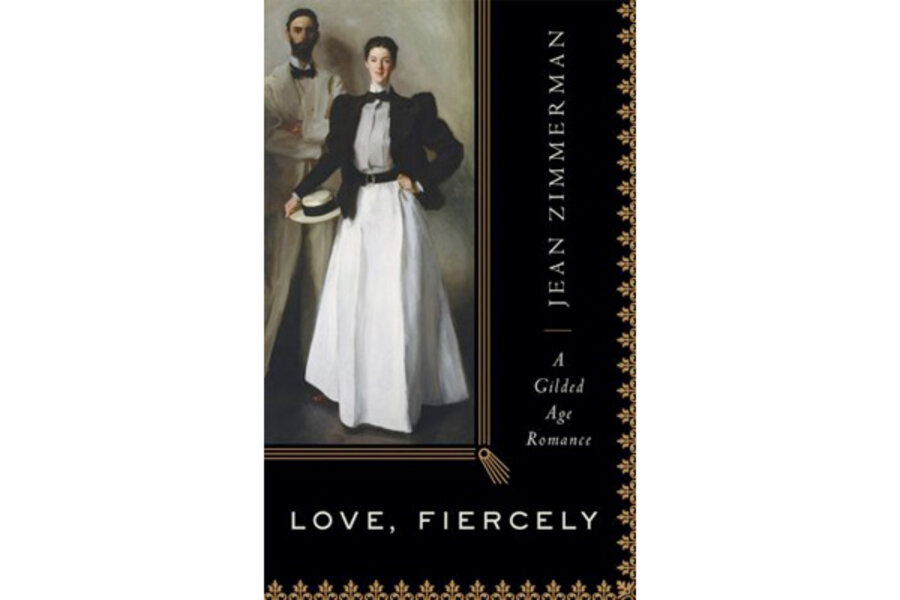

Jean Zimmerman bills Love, Fiercely: A Gilded Age Romance as "the greatest love story never told." Its subject is the marriage of Edith Minturn and Isaac Newton Phelps Stokes, wealthy, passionate, and progressive New Yorkers immortalized in a celebrated portrait by John Singer Sargent in 1897. The massive painting now hangs in New York's Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the depiction of Edith so intrigued Zimmerman when she first encountered it that she ended up unearthing all she could about the couple.

Edith and Newton, both born in 1867 in New York, lived "parallel lives." Children of privilege for whom "honeymoon" meant several years gallivanting through Europe and "cottage" meant a 100-room mansion in the country, their shared interests ranged from social justice to art. They married at twenty-eight, much later than was conventional at the time; their relationship was also unusually modern in being both "a romantic union and a partnership of equals."

Before posing for Sargent, Edith had achieved fame as the model for sculptor Daniel Chester French's colossal statue The Republic, seen by millions while positioned at the center of the 1893 world's fair in Chicago. In the years after the Sargent portrait, Newton -- who had trained as an architect and alternated "luxe, upscale commissions with reform-minded housing for the poor" -- developed a "ruinous" two-decade obsession with completing his sprawling history of early New York, the six-volume Iconography of Manhattan Island.

But the passages on the Sargent work itself, a wedding gift commissioned by a wealthy friend for the newlywed couple, are perhaps the book's most interesting. The artist, then among the world's most in-demand portraitists, had Edith pose in a blue satin ball gown, but after several weeks of sittings in his London studio, he felt the painting wasn't coming out right. One day Edith and Newton, rushing to their appointment, burst into the studio. Edith, in street clothes with her face flushed, "practically vibrated with energy," Zimmerman writes. Seeing her, Sargent abandoned the formal gown, saying, "I want to paint you just as you are." The resulting work, with Edith in the foreground and Newton behind her in the shadows, became a "cultural phenomenon" (as was customary, it toured galleries and museums despite being privately owned). With Edith's clothing and posture considered "shockingly mannish," the painting seemed to capture the spirit of a moment when the nature of American femininity was undergoing a historic shift.

While evocative and often captivating, Love, Fiercely cannot live up to its "greatest love story" billing. The historical record is too incomplete, and Zimmerman is too often forced to speculate. Just as Edith and Newton made ideal subjects for a portrait, their lives would provide rich fodder for a work of fiction. Perhaps one day someone will write it.

Barbara Spindel has covered books for Time Out New York, Newsweek.com, Details, and Spin.