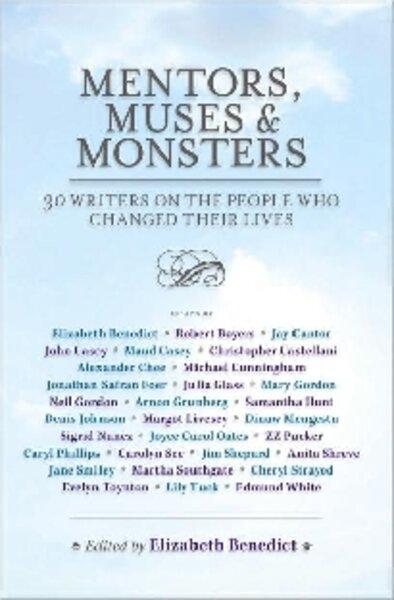

Mentors, Muses & Monsters

Loading...

Once, I was young and broke and living in Boston. It was 1991 – another bleak economic year – but, high on the town’s literary history, I moved there after graduate school to become a writer. Instead, the months sped past as I scored just one or two ill-paid freelance gigs.

Desperate, I cold-called a college alumnus, a top editor at a storied magazine, to ask for a job. He invited me in for an interview, skimmed the poetry manuscript that I’d brought, and then threw it down. “I really want to discourage you,” he said, and suggested that I try to sell things out of my car. The worst part was, I didn’t have one. I couldn’t afford it.

But that was long ago, and, by dint of time and luck, things improved. Still, the experience stuck with me, even drove me at points, and it comes to mind now on reading Mentors, Muses & Monsters: 30 Writers on the People Who Changed Their Lives, a mesmerizing book of essays by famous pens who themselves were once helped – or hurt – by established talents as they tried to climb their way up the literary ladder.

The book, edited by Elizabeth Benedict, beautifully captures the experience of being a literary aspirant – wide-eyed, enchanted by words, and eager for the tutelage of a mentor – one who’s already scaled the temple wall and emerged, shining, in a turret.

Reflecting on the state are some well-known voices ranging in tone from youthfully sanguine or self-serious (Benedict, Jonathan Safran Foer) to sensitive, solitary, or shy (Robert Boyers, Joyce Carol Oates, Jane Smiley). Together, they offer a real, giddy, and sometimes painful look at the ride that can result when a literary “name” suggests that one has – or does not have – talent.

For Benedict, the trip was launched on comments by novelist Elizabeth Hardwick, with whom she studied at Barnard in the 1970s. Of her wish to become a writer, she recalls Hardwick said, “I think you can do the work ... but you have to decide if you want such a hard life.”

To some, that might sound like scant praise. But Benedict took it as an endorsement. Similarly, as a college student, Foer found meaning in a gift that he gave to Israeli poet Yehuda Amichai – a snow globe that he handed to the literary icon at a reading – which the latter accepted, and kept.

Still, Foer wanted more: mentorship, acknowledgment, contact. “Why didn’t I write him letters?” he laments in an essay, written after Amichai’s 2000 death. “Why didn’t I insist on another meeting, which could have been done easily enough. (I’ve since heard of a number of people who got to spend time with him this way.)”

If this sounds at once plaintive and grandiose, nascent writers can be – Benedict warns – like amateur stalkers. It’s “an occupational hazard,” she says, adding, “Mentors are our role models, our own private celebrities, people we emulate, fall in love with” and – because who likes to obsess alone? – from whom we crave reciprocal notice.

But often, that’s pure fantasy; many of her contributors met with initial scorn. Critic Boyers – whose credits include Dissent and Partisan Review – saw his early verses jeered by Denise Levertov, then poetry editor for The Nation. “You’re obviously very bright,” he recalls her replying to his submission. “But I would recommend that you try something else.”

Then, he accepted her judgment. Today, he’s less impressed. “[A]n even brighter boy,” he growls, would have told her – harshly – what she could do with her advice.

Well, maybe. But can’t a new writer get turned away simply for being – well – bad? In the case of this book, the question may be: Does it matter? Here, pleasure lies not in sniffing out which of the contributors were wunderkinds – but in hearing their tales of desperation to be so deemed.

There are exceptions. Oates tells of being needled by fellow novelists John Gardner and Donald Barthelme: the former for diverging from his interests; the latter, for her bestselling status. And yet she comes off merely as baffled. “I never understood why so exceptional a personality,” she says of one of the two men, “wanted so badly to influence others.”

Similarly, novelist Smiley, passed over at the Iowa Writers Workshop for a teacher’s pet, describes her relief at being left alone: “I felt free and happy and more or less out to lunch. I cared hardly a thing for most of the teachers or the editors, but I adored my fellow students.”

So, what does this book teach us about literary mentors and muses – and their inverted monsterlike selves? What do they have to offer us? And is one ever present without the other?

Finally, what of the editor in Boston from long ago: Did he mean to be cruel – or to test my writerly mettle?

And I – having persisted all these years, despite his disinterest – have I, finally, passed?

Susan Comninos’s journalism has been published by The Atlantic Online, The Miami Herald, and Israel’s daily Haaretz, among others. Her poetry appeared most recently in the Forward. Her fiction is forthcoming in Quarterly West.