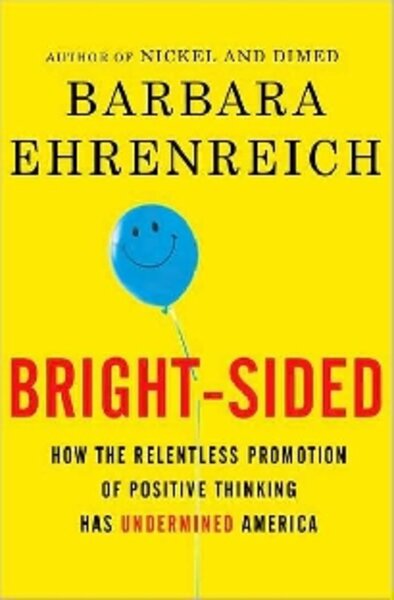

Bright-Sided

Loading...

Michael Moore and Barbara Ehrenreich may be soul mates. Both the gadfly filmmaker and Ehrenreich, a journalist and author, are social activists who have a bone to pick with big business and the way it treats workers.

In Bright-Sided: How the Relentless Promotion of Positive Thinking Has Undermined America, Ehrenreich proposes that America’s current fascination with self-help and “positive thinking” exacerbates the problem.

She’s not railing against hopefulness, optimism, or cheerfulness (well, maybe sometimes, when it’s cloying). She has a narrower target: the kind of self-hypnosis or thought control that people use on themselves to ignore “reality.” People are being taught a fantasy, she says, that if they wish hard enough, they can have whatever they desire, from a better job to a better body to better relationships.

Capitalism has encouraged this trend because it benefits from it, she says. Instead of taking political or social action to address lost jobs and workplace abuses, American workers have been hornswoggled into thinking it must be their own fault.

“When you lose a job, just shut up and scamper along to the next one,” is the message Ehrenreich takes away from “Who Moved My Cheese?” one of the self-help books she singles out for scorn.

But doesn’t a positive attitude help people during adversity, such as an illness? Not really, she argues. Positive “thought control,” she writes, “has become a potentially deadly weight – obscuring judgment and shielding us from vital information,” she says. We become Pollyannas in a dangerous world.

Classic books such as Dale Carnegie’s “How to Win Friends & Influence People” (1936) and “Think and Grow Rich!” by Napolean Hill to the 2006 bestseller “The Secret” promote the idea “that our thoughts can, in some mysterious way, directly affect the physical world,” she says

To buttress her case, Ehrenreich cites the most far-out-sounding self-help advice she can find – techniques such as keeping a $20 bill in one’s wallet to attract more money, or using crystals to control the world’s vibrations or magnetic energies.

The Christian megachurches now in vogue also receive their share of criticism – for buying into the positive-thinking mania that has invaded business, including “pastors, who increasingly came to see themselves not as critics of the secular, materialistic world but as players within it – businessmen, or, more precisely, CEOs.”

But, as Ehrenreich herself points out, the desire to bend the world to one’s personal will goes back not to early Christianity – in which Jesus speaks of “not my will but Thine be done” – but to ancient notions of “black” or “sympathetic magic.”

Ehrenreich traces American fascination with positive thinking to the late 19th century and Mary Baker Eddy, the founder of Christian Science. Unfortunately, here her scholarship shows itself to be sadly shallow and her summary of Eddy’s teachings is misinformed.

Ehrenreich proposes that today’s positive-thinking phenomenon evolved out of the New Thought movement. Perhaps. But any connection to Christian Science would be the result of distorted notions of Eddy’s actual teachings. She never mentions “positive thinking” in her voluminous published writings and counsels her readers to turn to God in prayer for help, not human willpower.

It’s also highly unlikely that Eddy, who wrote that “wealth, fame, and social organizations ... weigh not one jot in the balance of God” would have much truck with today’s get-rich-quick mentality.

Ehrenreich is an entertaining writer. She frequently tosses off clever lines, such as her gibe against the “spirituality” movement in corporations: “If there was a deity at the center of corporate America’s new ‘business spirituality,’” she writes, “it was Shiva, the dancing god of destruction.”

She’s also a skilled polemicist who knows how to build a compelling case by selectively sifting through the facts. (Where are examples of businesses that are getting it right? Are there none?) Many readers (including this one) could find much here with which to agree.

But one wonders if her concerns aren’t a bit overwrought. Does a dose of optimism or positive self-talk mean that people will suddenly abandon reason or humanity and wait for “the universe” to do all the work? Should we ban the “The Little Engine That Could” (“I think I can, I think I can”) from nursery shelves lest its “positive thinking” message corrupt young minds?

If the marketplace of ideas is at work, one can expect that the positive-thinking movement will be self-limiting. Americans are notoriously practical. If attempts to use the human mind to imagine health or wealth don’t put cash in pockets or bring peace of mind (as a good empiricist would expect), people are likely to lay them aside quickly and move on.

Gregory M. Lamb is a Monitor writer and editor.