The case for cancel culture: A millennial journalist’s take

Loading...

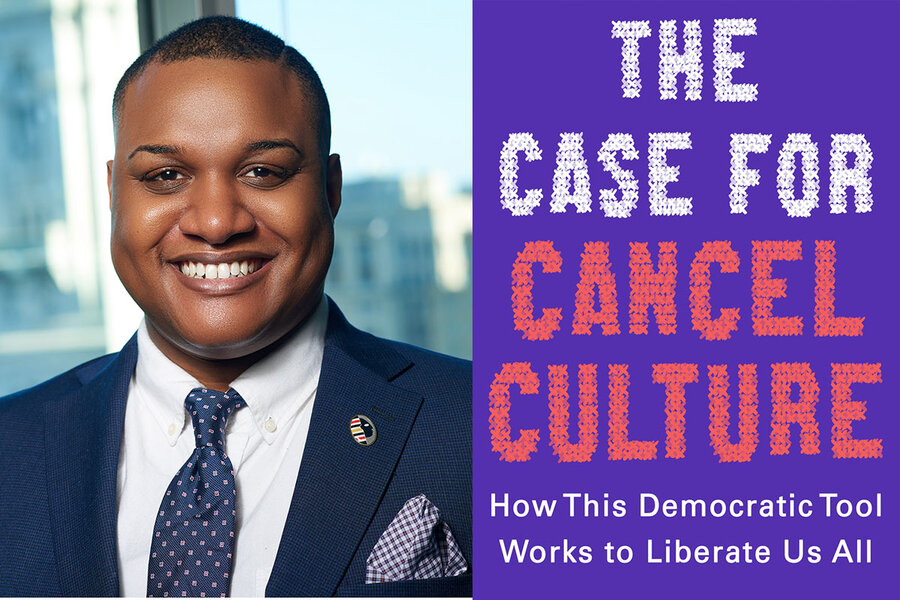

“I would argue that a world without cancel culture is a world where marginalized people don’t have access to having a voice,” says author Ernest Owens.

Cancel culture has been vital to the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, says the journalist, an editor at large at Philadelphia Magazine. He expounds on those ideas in “The Case for Cancel Culture: How This Democratic Tool Works to Liberate Us All.” The book argues that cultural boycotts enable ordinary people to hold the powerful to account.

Why We Wrote This

Cancel culture has become a powerful and controversial phenomenon. To understand why people engage in it, it’s helpful to hear from a millennial journalist who draws comparisons with social protest movements of the past, including sit-ins and boycotts.

Mr. Owens says that cancel culture has been used for centuries, from the Boston Tea Party and the Montgomery Bus Boycott to the Stonewall riots – 1969 protests in the LGBT community. “The history [of cancel culture] has been in every community, every group over the years and decades,” he says.

However, the tool has also become controversial for ending careers for one embarrassing mistake or incident, drawing ire from those who say people shouldn’t be canceled for their worst moment.

“I believe that there [are] opportunities for grace for people,” Mr. Owens says of those on the receiving end of cancel culture. “But I also think that we spend so much time worried about the offender rather than the offended.”

In 2019, Ernest Owens published a New York Times opinion piece, “Obama’s Very Boomer View of ‘Cancel Culture.’” The journalist was responding to remarks that the former president had made. Barack Obama had implored activists not to be overly judgmental of those who don’t measure up to “purity” tests. “That’s not bringing about change,” Mr. Obama said. In the opinion article, Mr. Owens countered that cancel culture has been vital to the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements. He expands on those ideas in “The Case for Cancel Culture: How this Democratic Tool Works to Liberate Us All.” Mr. Owens is an editor at large at Philadelphia Magazine and president of the Philadelphia Association of Black Journalists, and he hosts the podcast “Ernestly Speaking!” He spoke recently with the Monitor.

How do you define cancel culture?

Anything in which a person chooses to cancel ... a person, place, or thing that they feel like is detrimental to their way of life and their well-being.

Why We Wrote This

Cancel culture has become a powerful and controversial phenomenon. To understand why people engage in it, it’s helpful to hear from a millennial journalist who draws comparisons with social protest movements of the past, including sit-ins and boycotts.

Let’s say you don’t want to go to McDonald’s because you think the burgers are nasty. That’s a critique. That’s a matter of taste. That’s not cancel culture. But let’s say you said, “I don’t want to go to McDonald’s ... because they don’t give their workers a fair, livable wage.” You’re making a decision that is impacting ... the well-being of others.

In your book, you argue that cancel culture has been with us for centuries. Can you briefly summarize that idea?

You could talk about the American Revolution when they dumped the Boston tea [in the harbor]. They didn’t dump the tea because they thought the tea was bad. They dumped it because they were trying to fight against Great Britain’s taxation without representation. You look at the civil rights movement, the Montgomery bus boycotts. Stonewall was a riot: LGBTQ people pushed back ... because the police were consistently harassing them based on their identity. The history [of cancel culture] has been in every community, every group, over the years and decades.

If cancel culture has always been with us, what impact has social media had on it?

It’s easier for us to see it. Back in the day, you didn’t necessarily see Stonewall. You heard about it. We’ve seen an influx in the increase of coordinated protests across the country, [like] Black Lives Matter, because of the use of social media.

Do you think nonpublic figures should be canceled for their worst moment?

I believe that there [are] opportunities for grace for people. But I also think that we spend so much time worried about the offender rather than the offended.

Not all cancellations are equal. [Singer] Chrisette Michele, who ... did a performance [at Donald Trump’s] inauguration, lost her career. Is it fair? No, it’s not fair. So in this situation, you could argue that someone used cancel culture in a way that wasn’t as judicious or as graceful as some may have liked, and others may have found that it was [appropriate].

How does one ensure that cancel culture isn’t weaponized in ways that seem unfair?

I would argue that a world without cancel culture is a world where marginalized people don’t have access to having a voice.

You think about how we got marriage equality. I just got married in 2021. For years, we just accepted that gay marriage was never going to be a thing in this country. It was taboo to talk about it. ... It wasn’t until certain people ... came out, spoke out publicly, and began to demand and push more, calling out certain folks in public office, demanding those changes, that then we saw a societal shift that then influenced public policy. That’s cancel culture. So when I think about the major benefits in society that cancel culture provides, I really, with all due respect, cannot ever give that much credence to these small anecdotal incidents [of nonpublic figures being canceled], because I know overall the larger impact of what it benefits and provides.

What role is there for forgiveness for those that have been canceled?

Society is more forgiving and gives more grace than ever. I don’t really know too many people who’ve been permanently canceled. Cancellation looks like a timeout.

[Celebrity chef] Paula Deen was caught saying some inappropriate words. She lost some contracts with [the] Food Network and people were disappointed in her. She did some self-reflection. And a couple of years later, she’s on “Dancing with the Stars.” She’s got a career.

[Former White House intern] Monica Lewinsky’s evolution to not being canceled, or being uncanceled, by society has a lot to do with how society progressed in believing women. The progression of understanding sexual harassment and power dynamics in these roles, how we advanced sexual harassment policies, how we advanced talking about rape culture. All of these things set up the system to then turn around and reimagine her in a different way. So, we as society have to keep evolving.

Who is your audience for the book?

This book was important because it’s topical. It’s not for one type of community. It’s not for millennials. It’s not for conservatives only. It’s not for the boomers of the world that don’t get it. It’s for everyone, because there’s a lot of people, even in my generation as a millennial ... that don’t understand cancel culture. So I think it’s a great history lesson for anyone.