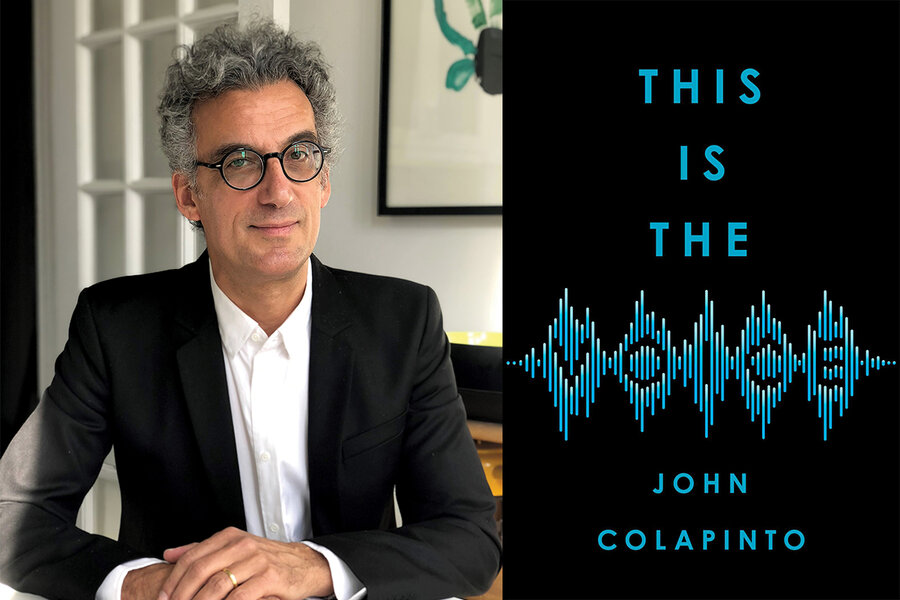

Q&A with John Colapinto, author of ‘This Is the Voice’

Loading...

What sets us apart from other animals? Some species are better at seeing, hearing, and smelling. But no creature has a voice quite as extraordinary as ours, and that’s made a huge difference, writes journalist John Colapinto in “This Is the Voice.” He talked to Monitor correspondent Randy Dotinga about unraveling the secrets of vocal communication.

Q: What is important to know about the human voice?

We are the planet’s most dominant species, and language gave us primacy. But we wouldn’t be speaking if we hadn’t developed the exquisitely complex mechanism to make the sounds that allow us to project our thoughts. When we speak, we rely on an amazingly complex set of movements – from our diaphragm up through our larynx, plus the closing and opening of our vocal cords – and all of that is coordinated with the way we’re moving our lips and tongue.

Q: What was surprising in your research?

One thing that amazed me was the degree to which human beings and non-human animals produce vocal sounds that are rich in content and understood across the species.

It should be obvious that when a dog growls, it’s being aggressive and trying to drive another animal away. But think about how we drop our own voices to say to a child, “No, don’t. Put that down!” Even birds – like my parakeet – produce low-pitched sounds like we do when they’re threatened.

It’s so clearly an evolutionary inheritance and made me grasp something I’ve always understood intellectually – how we really are on a continuum with animals.

Q: How do we teach babies to speak?

We automatically raise the pitch of our voices when we talk to them. We all do it, and even little children do it with their dolls, which suggests this is something that’s hardwired in us as a way to teach language.

One good physiological reason that we developed this: Babies can only hear at higher ranges. Only around puberty do we develop the full ability to hear lower tones. Somehow we know this as a species, so we go up into this range that just targets the baby’s ears and foregrounds our voice against all other sounds.

Q: How else do babies learn language?

We think that when we hear someone talking, they’re inserting little gaps of silence between words. But when we watch a movie in a language we don’t know, we realize it’s a ribbon of unbroken sound.

Now, as I speak, you are hearing the separate words as though they’re typed out on a page with a little space between them. That’s because when you were a baby, you listened to your parents talking. And you began to run a statistical analysis that told you where words are separated before you started to assign meanings to those little sound segments.

Think about a mother repeating things in an emphatic way: “Put the red block in the box.” This helps the baby segment the sound stream into words. So a baby would begin to think, “Oh, red seems to be a word. And box, because Mom keeps saying ‘box, box, box.’”

Q: What do our voices reveal?

Our emotional states can find their way into how we make molecules vibrate with our voices.

When the subprime mortgage meltdown was happening, I was freaking out. My then-9-year-old arrived home from school, and I didn’t want him to know. So I tried my usual cheerful “Hello,” and I thought it sounded normal. He immediately said, “Dad, what’s wrong?” He was hearing something that I was trying to keep out of my voice. Our voices really do give away these kinds of minute-to-minute moods.