‘I grew in leaps and bounds’: Dancer Misty Copeland reflects

Loading...

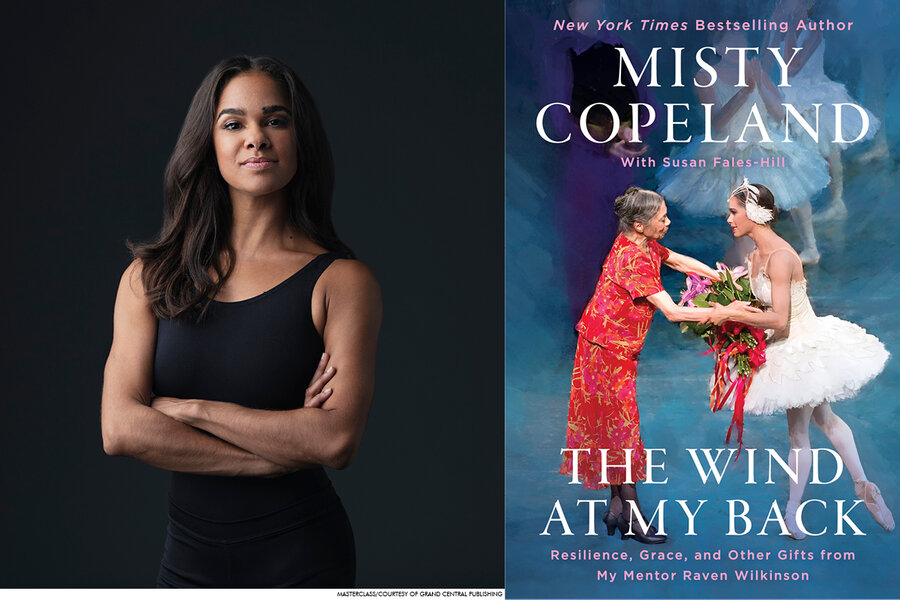

Celebrated ballet dancer Misty Copeland has a raft of “firsts” in her long list of honors and accomplishments, including her historic 10-year rise through the ranks of American Ballet Theatre (ABT) to become in 2015 the company’s first female African American principal dancer. That same year she was named one of Time magazine’s 100 most influential people. She is a bestselling author (“Life in Motion,” “Black Ballerina,” “Ballerina Body,” and “Firebird”) and has been the subject of TV features and the documentary “A Ballerina’s Tale.” In September, she launched the Misty Copeland Foundation with the goal of bringing greater diversity, equity, and inclusion to dance, especially by making ballet more accessible and affordable.

But as Ms. Copeland is quick to point out in her new book, “The Wind at My Back: Resilience, Grace, and Other Gifts from My Mentor Raven Wilkinson,” she has not done it alone. She has stood gratefully – and gracefully – on the shoulders of those who have come before her, especially the trailblazing Ms. Wilkinson (1935-2018), who Ms. Copeland credits as not just a mentor and role model, but also the perennial wind at her back. In 1955, the New York-born Ms. Wilkinson overcame skepticism and often open hostility to become the first Black woman to join a major classical ballet company, the all-white Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. For six years, her artistry was acclaimed in notable roles with the company, until racist threats during the company’s tours of the Jim Crow South nearly derailed her career. Ms. Copeland’s book chronicles their deep friendship and their individual paths in pursuit of artistic and personal fulfillment.

Your book pivots between your story and Ms. Wilkinson’s inspiring but sometimes horrifying experiences as a Black ballerina in the ‘50s and ‘60s. Were you hoping to highlight how much has changed as well as how much farther we need to go for equity and inclusion – in ballet and the world at large?

Yes, 100%. Learning of Raven’s journey and having her come into my life, I was struck by how much hadn’t changed. It made me feel even more responsibility to continue doing the work I’m already doing and bring the conversation to the forefront about the lack of diversity and inclusion in dance, and the power and impact dance can have in people’s lives. Raven and I come from such different backgrounds growing up, but as Black people had such similar experiences, and it’s important to acknowledge that we have a lot farther to go. I would say more hasn’t changed than has.

Your first real exposure to ballet was on a basketball court at the age of 13 in a program run by the Boys & Girls Club, and you’ve said that initially you didn’t really like ballet. What was it about the art form that ended up winning you over?

Initially, I was outside of my comfort zone and felt like I didn’t fit in. My whole adolescence, all I was trying to do was fit in and not have people know what was going on in my home life, which was really chaotic. But once I stepped into the ballet studio, I actually felt like I fit in, that I had everything it took to be a ballet dancer, and that was so empowering to find the perfect outlet to express myself and be heard. As a middle child of six children with my mom working many jobs, there was not a lot of focus on us as individuals. In the studio, I got that nurturing attention.

And found your voice?

Initially I did not like to speak. My nickname was Mouse growing up. But when I first experienced dance, ballet in particular, I learned a whole new language, and to express myself in that form was incredible. I grew in leaps and bounds in every way, and had a better understanding of myself.

You were in the midst of your professional career at ABT before you discovered Ms. Wilkinson through a documentary on the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and you say in the book that you were stunned to see a Black woman in the company in the ‘50s. Was that a turning point for you?

I didn’t realize there had been Black women at that level in that time succeeding in classical ballet. That’s not what we’re shown on TV and in history books. It was inspiring and intriguing, but at the same time made me really angry that I hadn’t learned about her, and it pushed me to think about my career in a different light, that I have a bigger purpose and responsibility. It made me start to dig deeper and learn about other Black ballerinas. She really changed the course of my career. I don’t think I would be a principal dancer if I had not stumbled upon her story.

You began your friendship with Ms. Wilkinson in 2011, and you say that she helped “bridge the gap between Misty the person and Misty the ballerina,” and that the greatest gift she gave you was hope. How has that sustained and motivated you?

She allowed me to understand how to translate the power you have as a performer onstage into the person you are as a human being. She set the example just by her daily actions, the way she treated people. The elegant, graceful, amazing ballerina she was onstage – she was that same person offstage. It allowed me to understand the power I hold and the symbol of being a Black body onstage.

Historically, young dancers of color have often been steered away from ballet toward modern dance. You’ve talked about defying your background, pedigree, and body type, but that at times you felt like a test case – a rare Black woman in a rarified art form representing generations of people who never felt welcome in that world. Is that a burden at times?

I am one of so many who have experienced this. I don’t feel like it’s a burden per se but more a beautiful responsibility to share my life and experiences. We only grow if we share and communicate and teach.

Do you think being cast in the iconic role of the Swan Queen in “Swan Lake” was a milestone that moved the needle on casting opportunities for Black ballerinas?

It was a huge deal at ABT, but it’s important to acknowledge other Black dancers, like Lauren Anderson [the first African American principal dancer at Houston Ballet in 1990]. But yes, it was a big responsibility. A lot of eyes were on me, a lot of pre-judgment that a Black woman couldn’t portray this role. But it’s a character in a fairy-tale ballet and the color of your skin should not limit you.

Do you feel a mission not just to be a role model, but to bring to light a legacy of dancers of color, like Ms. Wilkinson, who helped pave the way for your success?

I think that here hasn’t been enough documentation around our history in classical ballet. For me to have this platform and these opportunities to write books – it’s an honor to share these stories and I’m going to continue doing this.

Will your new foundation create the kinds of opportunities that Ms. Wilkinson, for example, never had?

Definitely that’s a big part of it. With everything I’m doing there’s a connection to ballet and bringing people in, and the foundation is hands on, on the ground, doing work directly connected to my experience starting out at a community center’s free ballet class, and that’s what we’re doing at five sites in the Bronx [in New York]. We’ve developed our own curriculum and framework to be adaptable, depending on the people in the room, and there’s live musicians – pianists, guitarists, percussionists. It’s not about finding the next Raven or Misty, but giving children an opportunity to experience a discipline and develop tools they can use in their lives and be future leaders in their communities.

How has having a 7-month-old son impacted your goals?

So much of my life has been focused on daily training eight hours a day and every little detail of preparing to go onstage. Now my focus is on him. But I can’t wait to go back onstage. I haven’t been onstage since December 2019. My plan is winter of 2023 looking at “The Nutcracker” as my comeback. Having experienced so much during the pandemic, the murder of George Floyd, I have more of a deep connection with myself and the things I want to say in ballet. I feel more competent in having discussions about race, feel more supported by colleagues in the dance world than before.

You’re 40, an age when many dancers stop performing. What does the future look like?

The future is dance, whether [it’s] my production company, the foundation, or Greatness Wins [an athletic apparel company]. All of these things will be forever part of my life whether I’m onstage or not.