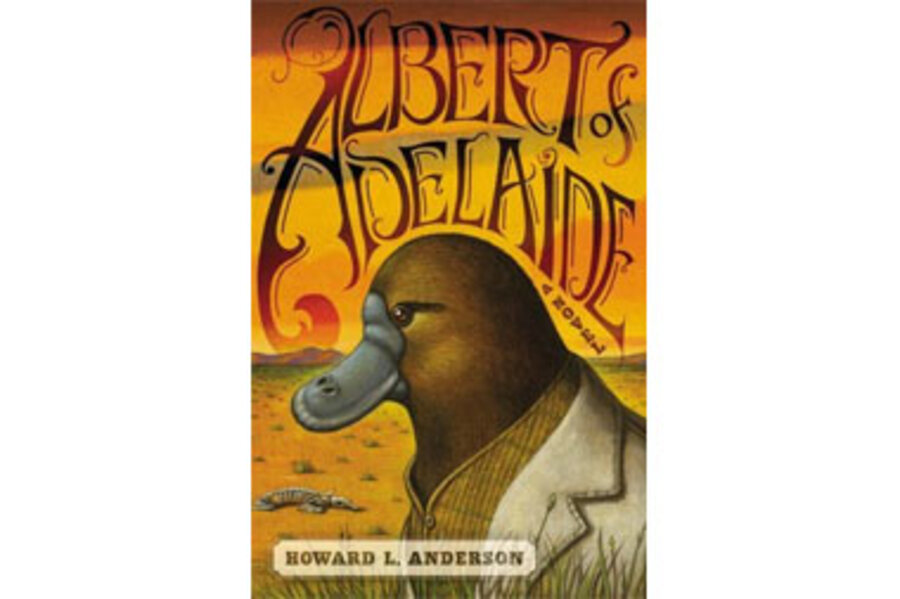

A platypus escapes from the zoo and heads for the Australian Outback in Howard Anderson's quirky first novel Albert of Adelaide.

While the desert might seem like an unlikely destination for the water-dwelling critter, the idealistic Albert, armed only with a soda bottle of water, is in search of the “Old Australia.”

“A semi-aquatic, egg-laying mammal of action” won't be a hard sell for any reader with school-age children and a cable bill, but the orphaned Albert would be a sympathetic hero even to those who have never heard of “Phineas and Ferb.”

Albert is befriended by Jack, a wombat with a handlebar mustache who likes to play with matches, but the Old Australia he encounters is more Wild West than promised land.

“At the zoo, Albert had been an object of curiosity and ridicule. In Old Australia, he found himself an object of hatred and mistrust.”

With society's pro-marsupial prejudice, the monotreme is eyed askance by everyone from drunk bandicoots to bar-keeping kangaroos and soon finds himself an outlaw on the run. Fortunately, Albert's got his own set of spurs, and these are loaded with venom.

Like Richard Adams's “Watership Down,” or George Orwell's “Animal Farm,” “Albert of Adelaide” is about more than furry animals, but Anderson's allegory about racism isn't an overly subtle one.

More fun are the supporting characters, such as a washed up Tasmanian Devil wrestler and a raccoon, late of San Francisco.

With its oddball cast of characters and frontier setting, “Albert of Adelaide” reminded me of a down-under “Rango” with a higher body count.