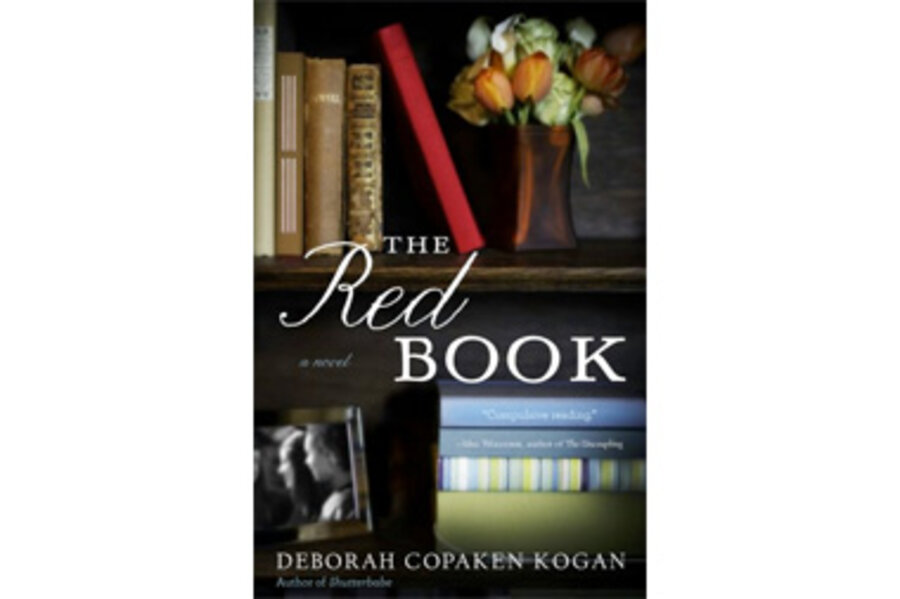

Attention, fellow mortals: A Harvard diploma does not come with a lifetime guarantee of financial and personal success, as illustrated by Deborah Copaken Kogan's new novel The Red Book. (Those of us in possession of degrees from lesser institutions of higher learning can take solace from this fact.)

Twenty years after graduation, former roommates Mia, Addison, Jane, and Clover are back in Cambridge, Mass., for their reunion weekend in 2009.

The first signal that they haven't been terribly upfront with one another (or themselves) about their lives is when free-spirited “artist” Addison is arrested, in front of her children, for almost six figures' worth of unpaid parking tickets. Addison is married to a “novelist,” but all of their income comes from his-and-hers trust funds, and their children spend more time watching Internet porn than doing homework.

Commune-raised Clover had done very well for herself on Wall Street until her firm, Lehman Brothers, collapsed the fall before. Mia has abandoned her acting dreams for a comfortable life as the wife of a Hollywood director, complete with four children and a vacation house in the south of France. Jane Nguyen Streeter, a Paris-based journalist, is trying to deal with the collapse of her industry and the death of her mother, along with discovering via email that her French lover had an affair while she was caring for her dying mom.

Former photojournalist Copaken Kogan's second novel uses the Harvard Alumni newsletter, the Red Book, as a framing device for her novel. The implication is that the university's graduates owe it to the world and their alma mater to bring home the MacArthur genius grants and record-setting IPOs. Ordinary life as, say, a high school history teacher or Subaru salesman, is a waste of the famed diploma.

The discrepancies between the front the characters present in their entries and their actual lives makes for an entertaining juxtaposition as the main characters encounter old lovers and people who knew them before they had stretch marks. With its college reunion setting, “The Red Book” invites comparisons to the “The Big Chill,” except these children of the 1980s had precious little idealism to lose.

“The Red Book” is entertaining, but Copaken Kogan needs to lighten her touch: It's not enough for one character to be so self-absorbed that he has never changed a diaper or showed up for a school play; he has to be anti-Semitic, as well. If one affair makes for a juicy plot twist, three must be even better. And a late-breaking tragedy is telegraphed chapters ahead of its arrival.

Despite its flaws, “The Red Book” is an enjoyable read that believes that self-knowledge is worth more than a $120,000 education.