A&E would have a field day with Arthur Opp. He hasn't left his house in 10 years and, by his own estimate, he weighs somewhere between 500 and 600 pounds.

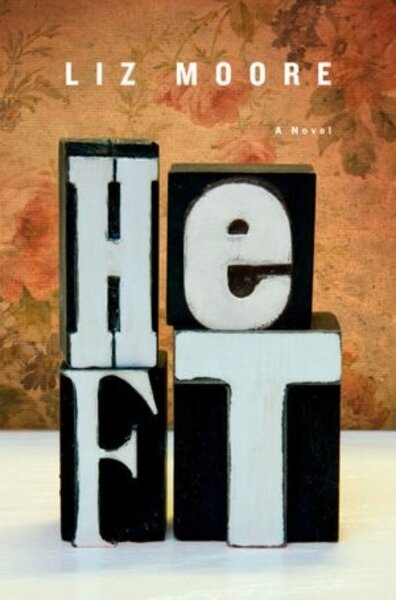

“Despite this I am neither immobile or bedridden but I do feel winded when I walk more than six or seven steps, & I do feel very shy and sort of encased in something as if I were a cello or an expensive gun,” writes Arthur at the beginning of Liz Moore's delicately poignant novel Heft.

Eighteen years ago, Arthur was an English professor teaching a blue-collar student from Yonkers who, instead of analyzing texts, would use her papers to call Medea a bad mom, over and over again. Charlene Keller was out of style, even then, but rather than roll his eyes and make fun of her naivete, Arthur, who sees the beauty in unbeautiful people, is charmed.

He loses his job over their friendship – it barely qualifies as dating – and she drops out of school. The two keep in touch through letters, which remain Arthur's only contact with the outside world besides the delivery men who bring him his daily supplies.

Then, Charlene asks him to meet her teenage son, and Arthur has to tell the truth of what his life has become. As it turns out, Charlene hasn't been up front about a few things, too.

“Heft” moves between Arthur, who hires a cleaning lady to try to make the house passable for visitors, and Charlene's son, Kel Keller, a star baseball player who no longer quite fits in Yonkers, thanks to the upscale school his mom got him into. (He doesn't quite fit in there, either, but Kel has mastered the art of camouflage that eluded both Arthur and Charlene.) Charlene's biggest dream has always been for Kel to go to college. He can't imagine his mom surviving with him far away and wants to make a pile of money, now, so that he can take care of her and “force” her to get well.

To describe too much about the plot is to ruin “Heft,” but as time goes on, a worried Arthur takes the drastic step of calling. “You've reached the Kellers, his voice said. We can't take your call right now. You know what to do. I waited for the beep and then I hung up. Because I didn't.”

The psychology of how Arthur got to his present size may seem pat, and the fact that his last day outside was Sept., 11, 2001, made me sigh, but I was so busy hoping things would work out for Arthur and Kel that those flaws barely registered on first reading.

Moore doesn't shy away from Arthur's eating habits, which may put some readers off, but that would be a real shame. In her story of the agoraphobe and the athlete, she's created a novel whose gentle understanding creates a beauty that stays with you long after the book is done.