From ashes of fire, Maui’s ‘ohana spirit rises

Loading...

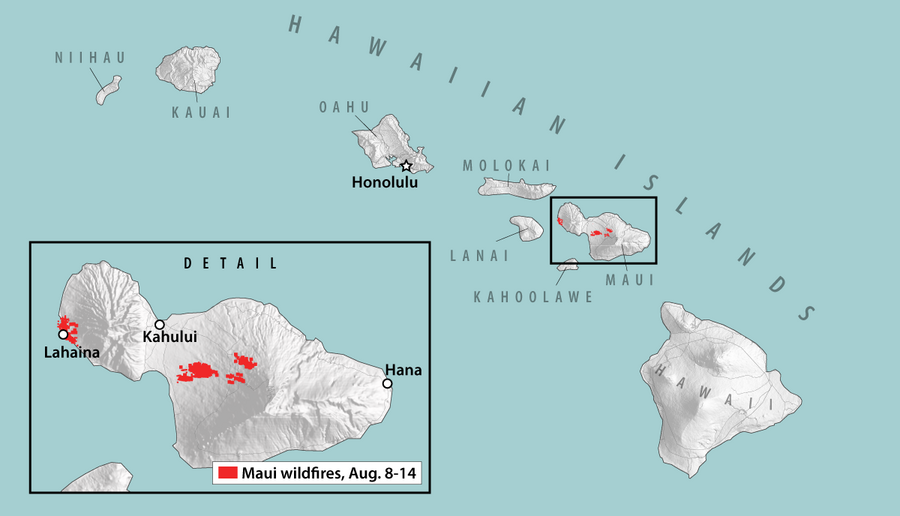

| MAUI AND OAHU, HAWAII

Survivors of the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century know the island of Maui as more than palms, peaks, and waves. Beyond its vacationland veneer, the historic coastal town of Lahaina holds sacred sites for Native Hawaiians, and has for generations been home to various cultural groups and social classes.

Recovery will likely take years, says the governor. Thousands have gone without power in recent days or have been displaced in shelters. Painstaking search and rescue continues.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century has shocked the island of Maui. The road to recovery may be long, but grief has also brought generosity.

Yet just as grief follows tragedy, so does giving. Local and state residents, as well as mainlanders, have mobilized a range of donations to help residents, referred to as ‘ohana, or “family,” in Hawaiian. An effort mostly led by Native Hawaiians has brought generators and other supplies to survivors by boat, as others help keep track of lists of missing persons.

“Generosity has just been overwhelming,” says Walter Chihara, a 50-year resident of Lahaina who lost his home.

Maui locals have raised their hands to help. Many have prepared free meals on the site of the University of Hawaii Maui College culinary arts program. On a recent kitchen shift, Truman Taoka diced vegetables.

There are “all these people from other parts of the island helping out,” says the Maui-born-and-raised volunteer. “We are a small community, so everybody knows somebody on parts of the island.”

Sports journalist Walter Chihara of Lahaina News has covered it all in his community on Maui’s west coast – swimmers, canoe clubs, and surfing stars. He’s spent five decades in the historic coastal town.

As of last week, however, much of his town is gone. That includes the space where he held Lahaina Dojo, teaching Japanese karate. Houses of worship and museums have disappeared.

So has his home.

Why We Wrote This

A story focused onThe deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century has shocked the island of Maui. The road to recovery may be long, but grief has also brought generosity.

Though his family is safe, Mr. Chihara says, “we’re really trying to find out about all the neighbors.”

Survivors of the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century know the island of Maui as more than palms, peaks, and waves. Beyond its vacationland veneer, Lahaina holds sacred sites for Native Hawaiians, and has for generations been home to various cultural groups and social classes.

Recovery will likely take years, says the governor. Thousands have gone without power in recent days or have been displaced in shelters. Painstaking search and rescue continues, meanwhile, as locals with missing loved ones are encouraged to submit DNA tests to help identify remains. Ninety-six people were confirmed dead as of Sunday night.

Yet just as grief follows tragedy, so does giving. Local and state residents, as well as mainlanders, have mobilized a range of donations. An effort mostly led by Native Hawaiians has brought generators and other supplies to survivors by boat, as others help keep track of lists of missing persons. Mr. Chihara is among the grateful recipients, flooded with clothing and funds. As healing takes time, survivors like him are embracing the uplift.

“Generosity has just been overwhelming,” he says.

Responding to fire’s aftermath

Since three wildfires began on Maui last Tuesday, most of the devastation has centered on Lahaina. Many attempting to escape, with no other way, threw themselves into the ocean. The U.S. Coast Guard rescued 17.

The fires’ causes remain unconfirmed, but they were fueled by strong winds and dry conditions. The perimeters of the fires are now largely contained.

Local leaders encourage solidarity among the larger Hawaii ‘ohana, a cultural belief in the power and extension of family. Hawaiian is an official language of the state along with English.

“If you have additional space in your home, if you have the capacity to take someone in from west Maui, please do,” said Democratic Gov. Josh Green last week.

To ease the sudden demand, Hawaii’s capital, Honolulu, has paused a short-term rental rule, the Honolulu Civil Beat reports, and more temporary housing options may come with the help of hotels. Residents may also apply for certain aid through the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Officials ask for patience during the difficult process of victim identification.

“Everybody wants a number,” Maui Police Chief John Pelletier told a packed room of reporters Saturday. “Do you want it fast, or do you want it right? We’re going to do it right.”

Maui locals, meanwhile, have raised their hands to help. Many have prepared free meals on the site of the University of Hawaii Maui College culinary arts program, an initiative also involving the nonprofit Common Ground Collective.

On a recent kitchen shift, Truman Taoka dices vegetables.

There are “all these people from other parts of the island helping out,” says the Maui-born-and-raised volunteer. “We are a small community, so everybody knows somebody on parts of the island.”

Barriers to action

Still, frustration has mounted over initial barriers to action. Firefighters lacked access to enough water, reports The New York Times. And people in Lahaina lacked notice that a disaster was fast approaching.

Chris Phillips says he received “nothing” to warn him of the fire. The surfer watched as wind shook the windows of his apartment, and then smoke choked the sky.

“I have to find a job and start all over again,” he says at the Hawaii Convention Center, opened for evacuees, where he’d been sleeping in Honolulu.

The state attorney general has announced a review of “critical decision-making and standing policies” around the fires.

“The records show that neither the State nor County activated the sirens,” which are typically used for storms and don’t necessarily signal the need to evacuate, but rather indicate the need to seek more information, writes Adam Weintraub, external affairs director at the Hawaii Emergency Management Agency, in an email. Alerts sent by officials to cellphones, televisions, and radio stations may have been disrupted by power or cellular outages.

Nina C., while lodging at her Lahaina timeshare last week, only learned of the fire’s severity through her sister in California, after several attempts to secure cell service. Ms. C., who declined to have her last name printed for privacy, fled with her son and husband, with whom she honeymooned on Maui years ago.

“We will continue to come back,” she says. “Not just because we love it,” she adds, but to keep supporting the local economy.

The cost to rebuild, by one estimate, could take $5.52 billion. Still, some residents are already wary of rebuilding Lahaina, once the capital of the Kingdom of Hawaii, in a way that mainly privileges wealthy property owners and tourists. That worry parallels experiences of displacement throughout Hawaii, including the overthrow of the royal government and annexation of the islands by the United States in 1898.

Communities “come together”

For some survivors, focusing even on day-to-day needs has proved overwhelming.

“Still, I’m like, confused,” says Héctor Bermúdez, outside a Wailuku shelter east of Lahaina on Saturday. “I don’t even know what day is today.”

The Lahaina resident fled with only his wallet. Family and friends have offered him housing in California, Texas, and Florida, says Mr. Bermúdez, but he’s unsure of next steps. He’s building back his world one donation at a time: fresh white towel, new blue shirt.

Shelby Scofield’s family pitches a tent nearby. Despite the difficult road ahead, Mx. Scofield says they’ve been moved by support.

Before the fire, the therapist had helped people transition out of incarceration, homeless shelters, and substance-use treatment centers into housing. Now clients are helping ease Mx. Scofield’s own transition, calling to check in and bringing over ice and clothes.

Also delivered this weekend was the pet guinea pig, which somehow survived.

“The communities just come together,” says Mx. Scofield, “which is what is beautiful about Maui.”

We encourage people seeking to help to research reputable aid groups before donating. The governor of Hawaii suggests supporting the following organizations: Hawai‘i Community Foundation – Maui Strong Fund, Council for Native Hawaiian Advancement – Kāko‘o Maui Fundraiser, and Maui United Way – Maui Fire Disaster Relief.