A quest to preserve Palestinian heritage in the digital stacks

Loading...

| Ramallah, West Bank

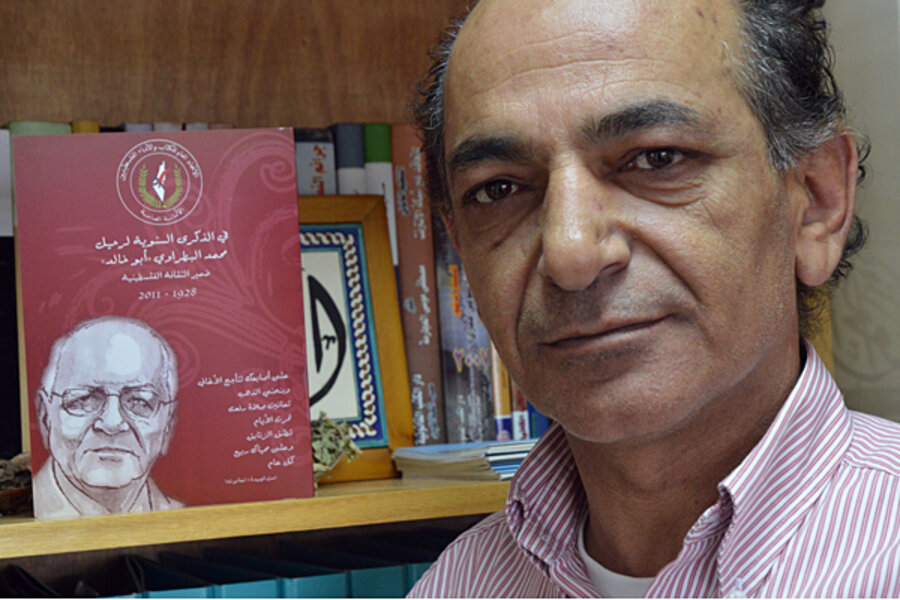

As the son of a man who had a personal library of some 15,000 volumes, Sami Batrawi loves the feel of turning the pages of a book rich in history.

But after years of trying and failing to establish a Palestinian version of the Library of Congress, he would now content himself with swiping a finger across an iPad if it meant being able to access the wealth of literature about Palestinian national heritage.

“We didn’t succeed to have our traditional national library but I think now we can do something else,” says Mr. Batrawi, the director-general of the intellectual property unit at the Palestinian Authority’s Ministry of Culture and one of less than a dozen Palestinians with a graduate degree in library science.

So now Batrawi is trying to get the PA to approve an online Palestinian national library, which would provide digitized access not only to Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza but also to Palestinian refugees and expats spread out across the Middle East, Europe, Latin America, and the US.

But his proposal has been mired in government bureaucracy for more than two years, and he faces a major hurdle because the PA has yet to establish a uniform copyright law. (Those efforts are also tied up in bureaucratic reviews.)

“If there’s only one minister who is interested in this project, he can get the signatures,” says Batrawi.

Before the 1948 nakba, or catastrophe, in which at least 700,000 Palestinians fled or were forced to leave their homes amid fighting over Israel’s declaration of independence, many Palestinians read widely and had private book collections as well as community libraries. But many of those books were lost in the nakba; to this day, some 30,000 volumes labeled “abandoned property” are collecting dust in the basement of Israel’s National Library.

Batrawi was part of an effort to build 120 new children’s libraries after the 1993 Oslo peace agreement with Israel, but it’s perhaps an even harder battle to restore the love of reading.

As part of the virtual library project, he hopes to introduce workshops, TV shows, and university programs to teach Palestinians to make better use of the computers and Internet access that many families have in their homes.

“You will not see that they’re using it in the right way to make research,” says Batrawi, noting that many use their computers mainly for games, Facebook, and online chatting.

Even among those who value Palestinian national heritage, Batrawi faces an additional hurdle: fear that Israel could destroy that national treasure in one fell swoop if it were located in one building.

“Why do you want to collect all our heritage in one building?” is a key criticism he has heard. “What if the Israelis come and they destroy it? How will you protect this?”