Why one Yemen provincial governor says he can't fight Al Qaeda

Loading...

| Zinjibar, Yemen

Ahmed al-Misri rues the day he took the job two years ago as governor of the southern Yemeni province of Abyan, fast emerging as a key battleground in the fight against Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP).

In a frank assessment from his heavily guarded residence outside the regional capital of Zinjibar, Mr. Misri talks of his difficulties in reining in Al Qaeda when the central government in Sanaa is diverting troops to fight a rebellion in the north and a secessionist movement that is gaining ground in the south.

“In all honesty, [government control] is not so strong,” said Misri in an interview with four journalists attended by several local subgovernors and the regional army chief. “We don’t have enough weapons, we don’t have enough soldiers. Our resources are so stretched that if something happens in the countryside, we can’t respond because there are no helicopters of airplanes.”

Misri, a member of the ruling party and close regional ally of President Ali Abdullah Saleh, is known for his outspoken views. But with troops and resources thinly spread on three different fronts, his appeals to the government appear to be falling on deaf ears.

Yemen, the poorest country in the Arab world, has come under intense international pressure to show it reining in extremists after Al Qaeda in the Arab Peninsula claimed responsibility for the botched bombing of a Detroit-bound airliner on Dec. 25.

The government has insisted it does not need US military intervention in its fight against the extremists, and has pointed to recent air and ground strikes that killed Al Qaeda members – including one today that Yemeni officials said killed six Al Qaeda militants – as proof that it is winning the battle.

It has also claimed to bolster forces in regions where Al Qaeda is believed to be strongest, such as Abyan, a region with a population of roughly half a million.

Misri said, however, there have been no reinforcements in his region. Instead, army chiefs have switched units in the north with those in the south, keeping numbers steady but giving the appearance of troop increases.

When asked about Misri’s claims, Yemeni Foreign Minister Abu Bakr al-Qurbi said he could not comment because it was a security matter.

A Yemeni security official, who asked not to be named because he was not authorized to speak on the issue, said that troops were needed in other provinces and would only be moved to Abyan if there was “a clear target.”

Al Qaeda makes inroads with cash, wells, AK-47s

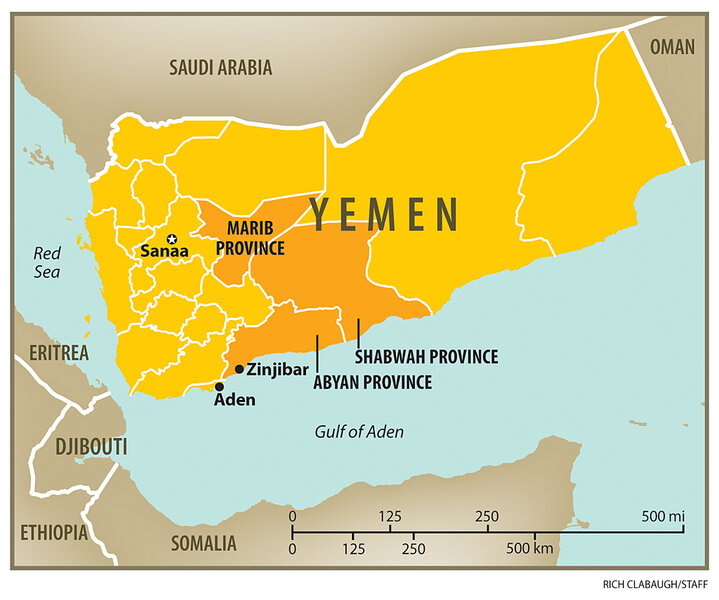

Many fear that Yemen is in danger of becoming a failed state. Along with Abyan, the regions of Shabwa and Marib are often cited as strongholds for AQAP.

Local chiefs describe how deep in the mountains of Abyan, Al Qaeda militants move easily among the impoverished Bedouin villages, where unemployment is rife and the name of Al Qaeda unfamiliar to many.

Misri says that Al Qaeda’s presence in the region has grown in the past six to eight months, bolstered by financing brought over by Al Qaeda members from Saudi Arabia. Many Al Qaeda fighters have fled Saudi Arabia following a Saudi crackdown.

When Yemen-based Al Qaeda formally merged its operations with the Saudi elements early last year, analysts said it provided an important boost to the organization.

Although the group makes initial contact through a religious dialog, its members provide crucial services to local communities, distributing aid in the form of cash, AK-47s and help in building infrastructure, such as wells, said Misri.

“Say the government is paying someone $50, they will pay $100,” he said.

In return, they receive protection from the tribes and recruit foot soldiers to their cause, he said, citing local chiefs and officials based in these areas.

Why villagers may turn blind eye to Al Qaeda

December air strikes, reported to be US-backed, had tragic consequences when – according to Misri’s people – an entire village of mainly civilians was wiped out in a remote Bedouin village in Abyan. When a local chief navigated the mountain roads to reach al-Majalah several hours later, he found just five survivors – an elderly woman, three young girls, and a 16-year-old boy.

According to Misri, 14 of those killed were Al-Qaeda. Another 45 were civilians.

The strike has provoked deep anger among villagers, who are demanding an apology from the government.

“If the government doesn’t give a clear apology for what happened, people will turn a blind eye to the presence of Al Qaeda members,” said Misri, adding that local leaders have offered their condolences.

Taking the wheel of his jeep, Misri leads a security convoy formed of two pickups filled with soldiers and a police escort for a short tour of nearby Zinjibar. He claims that he is not worried about attacks on him as an act against him would be an act against his tribe.

Just a few miles from his residence, he points out the bullet-scarred house of a prominent separatist leader, where a tense shootout last July left at least 12 dead.

Misri: Aid imperative to ally tribes against AQAP

Indeed, Misri is fighting a war on two fronts – the Al Qaeda threat and a separatist movement that seeks an independent South along the lines of the former British protectorate that later yielded to communist rule.

Secessionists are seeking to throw off what they call a government “occupation” that treats southerners as second-class citizens. They accuse the government of ignoring the interests of the south and using its dwindling oil resources to benefit Saleh, who united North and South Yemen in 1990, and his inner circle.

While the separatists say they seek a split through peaceful means, government authorities say several demonstrations have turned violent, with armed protesters setting up road blocks, stealing cars, and breaking into government offices.

Misri estimates that unemployment stands at 50 percent in Abyan, considerably higher than the estimated national average of 40 percent.

Unless international aid is forthcoming to tackle the root problems, the strength of resistance groups will grow, he warns.

“We need more help to get the tribes to kick them [Al Qaeda] out,” he said. “The government does not have the resources to do that.”