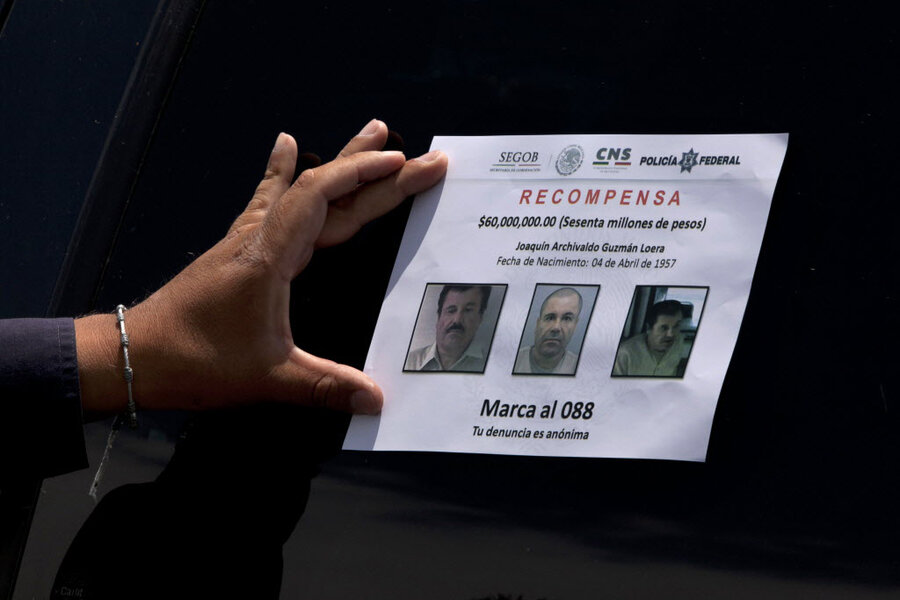

'El Chapo' escape: Why did it take 18 minutes to notice Guzmán was missing?

Loading...

It took at least 18 minutes before anyone was alerted to the escape of the drug lord Joaquín "El Chapo" Guzmán, two lawmakers said Thursday one day after touring the escape tunnel used by the prisoner.

Aleida Alavez, deputy of Mexico's leftist Democratic Revolution Party, told The Associated Press that when National Security Commissioner Monte Alejandro Rubido was asked on Wednesday about the time elapse in Mr. Guzmán’s escape, he first hesitated, but then answered that the report came 18 minutes after the escape.

Adriana Gonzalez, deputy of the conservative National Action Party, also said she did not hear Mr. Rubido give that account, but according to personnel monitoring the cameras, Mexico's most prized prisoner had about 20 minutes to slip into a mile-long tunnel Saturday night.

Ms. Gonzalez said she had been told that no one person was exclusively monitoring Guzmán at the time of the escape, but prison personnel was monitoring the video feeds from 20 separate cameras on two screens.

The footage of Guzmán’s cell released to the public Tuesday showed he disappeared from the camera sight at 8:50 p.m.

Gonzalez was shown about five minutes footage of Guzmán’s cell the night of his escape, and she says all that was visible was an empty cell. "The image stayed the same and time is passing and minute 56, 57 and no one appears," she said.

Officials have not yet publicly announced the time lapse in Guzmán’s escape.

The case is still under investigation. The Attorney General’s Office is both studying the escape and looking into any possible breach of prison protocols or intentional delay in issuing an alert after Guzmán’s escape.

At least 30 prison officials are being questioned over the breakout.

“Mexican public opinion already perceives that there’s collusion between the armed forces and organized crime,” Armand Peschard-Sverdrup, senior associate for the Americas program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies told The Christian Science Monitor's Whitney Eulich shortly after the escape. “This [escape] only fuels that perception, whether it’s merited or not."

Jorge Chabat, a drug war and security expert at Mexico City’s Center for Research and Teaching in Economics told the Monitor that Guzmán’s capture was a huge win for Mexico President Enrique Peña Nieto. “But his escape is far worse than had he never been captured in the first place... I’m not sure how they can recover from this, but the next few days will be key,” he adds.

Guzmán, leader of the Sinaloa cartel, previously slipped out of Mexican prison in 2001 in a laundry basket. He was not recaptured until February 2014. US agents’ documents obtained by the AP suggest he began planning his escape immediately after that arrest.

This report includes material from the Associated Press.