Karadzic ends boycott of trial seen as key to Balkans closure

Loading...

| The Hague, Netherlands

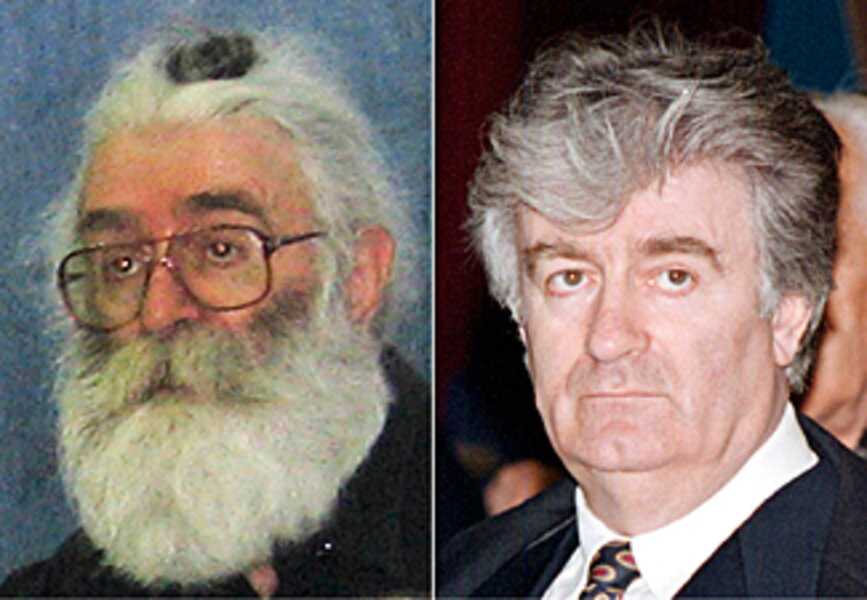

Radovan Karadzic broke a boycott on his Yugoslav war crimes trial today to ask for 10 more months for his defense against genocide charges in Bosnia.

"I would really be a criminal if I were to accept these conditions," the former Bosnian Serb president told Judge Kwon O-gon, who is considering appointing a stand-by council for him.

Mr. Karadzic, captured after 11 years on the run, says the UN tribunal that has prosecuted 159 persons for Balkan war crimes is "illegal" – but says he doesn't want to boycott it and needs more time.

Karadzic is considered a "big fish" at the tribunal. But the crimes he is charged with today took place more than 15 years ago – a time Europe was celebrating the end of a 40-year cold war, and Beethoveen's Ode to Joy was still reverberating at Berlin's Brandenburg Gate. The Balkans war ended much of the joy.

Who was Radovan Karadzic, then?

Balkan historians and Sarajevo experts say Karadzic always had a thirst for fame. He was a small- town Montenegrin, a bootmaker's son who moved from the hills to big city Sarajevo seeking greatness. He claimed lineage to Vuk Karadzic, father of the Serbian language. He published three volumes of poetry, much of it harboring a Sarajevo grudge: "The city lies ablaze like a rough lump of incense."

But he cut little weight among city blue-bloods even as he shape-shifted, for a time, into a Green Party politician and a soccer-club psychiatrist, or stood with Muslim leader Alia Izetbegovic to honor Muslims and Serbs killed in World War II and vowed never to let the Drina River flow with blood again.

Yet Mr. Karadzic's thirst for fame helped him become a key "front man" for Serb strongman Slobodan Milosevic's bloody project of "greater Serbia," experts say. His venue: a war that dissident poet and Czech president Vaclev Havel called an attack on "civilizational values," when he pressed for military intervention in the 44-month siege of Sarajevo that fellow "poet" Karadzic helped direct. Barring the arrest of Bosnian Serb Gen. Ratko Mladic, Karadzic's war-crimes trial is seen as a last chance to bring closure to the Balkan tragedy.

Long clashes over Sarajevo

From 1991-95, US and European capitals clashed over how to deal with children and grandmothers shot in the streets of a European city by Serb snipers in the hills above a city of Orthodox, Protestant, Roman Catholic, Muslim, and Jewish worship sites. Leaders weighed the cost of stopping the carnage against the meaning of not stopping it. Ineffectual blue-helmeted United Nations peacekeepers were sent in. At one point, Karadzic was so indispensable to the UN process that he could avert UN airstrikes against his own forces as they closed in on unarmed Bosnian Muslim "safe havens," usually on grounds that strikes would thwart a pending peace deal. The result: the Srebrenica massacre.

Yet, "before the war, Karadzic was a nonentity," says Bosnian historian Marko Attila Hoare. "He was an embezzler, an opportunist. He has nothing to say, makes no intellectual contributions. His background is primitive."

Historians stress Karadzic's country background in the Balkan context. "Milosevic tried to cut a figure as a modern European statesman; Karadzic was cruder," says Mr. Hoare. "In October 1991, he openly tells Muslims in the Bosnian parliament that he will eliminate them. He's seen as a kind of wild man, doesn't know how to dress properly, but no one in Sarajevo could believe he would be able to destroy so many lives."

Izeta Bajramovic, a Sarajevo shopowner who knew Karadzic as a boy in the 1960s, told the Los Angeles Times in a wartime interview that Karadzic used to beg her for free pieces of baklava: "He was skinny, hairy and shy, very, very shy…. I used to feel sorry for him. He was provincial, a typical peasant lost in the big city."

Karadzic married a city girl, got a degree in psychiatry, and bounced around the margins of literary circles; he lived in New York City for a year. He was a police informer and later charged with embezzlement in Sarajevo, but never served the sentence.

Powerful Serbian nationalist elixir

Yet a two-year stint working a Belgrade health clinic in 1986 likely allowed Karadzic to drink deeply from a powerful new Serbian nationalist elixir. The "Memorandum" from the Serbian Academy of Sciences in 1987, written by intellectual-patriot Dobrica Cosic, became a blueprint for breaking up Yugoslavia. In multiethnic Yugoslavia, socialist and egalitarian, the "Memorandum" was a bombshell calling for Serbs to unite. Mr. Cosic had been an older friend to the young Karadzic when the former's views were anathema. By the late 1980s, Serb nationalism was back; many Serbs were tired of and irritated by put-downs in Tito's Yugoslavia.

Armed with new articulations of Serb anger, Karadzic was able to rise in the heady days after the Berlin Wall fell popularly called "the end of history."

With Milosevic pulling the strings, he would soon reintroduce Europe to a past all too ugly and recent. The war he helped facilitate, with 200,000 killed, was at its core a rejection of European postwar values: reversing the "never again" judgments of Nuremburg against Nazi fascism, reintroducing Guernica-like horror and fear, and insisting that ethnic identity and national honor were more powerful impulses than democratic rights and dignity. Milosevic died during his trial in The Hague in 2006.

The 39-page charge outlined at the Yugoslav tribunal in late October by prosecutor Alan Tieger, accuses Karadzic of participating "in an overarching joint criminal enterprise to permanently remove Bosnian Muslim and Bosnian Croat inhabitants from the territories of Bosnia Herzegovina claimed as Bosnian Serb territory."

The tribunal opened in 1994, in the midst of the war, amid great doubt. But it has proved a watershed for international justice.

"The Yugoslavian war was a defining moment for justice," says Hans Corell, chief legal adviser to former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan. "After the wall fell and the cold war ended, a greater awareness began to force itself into the world public. The war-crimes tribunals were part of a view that you can't conduct mass murder and get away with it by hiding behind the sovereignty of the state."

South African judge Richard Goldstone, who, as the tribunal's first prosecutor, indicted Karadzic in 1995, defended the court, telling CNN recently that the "movement forward has been very impressive…. Fifteen years ago, there was no international justice at all. It is becoming a force."

Today, says Tim Judah, author of several works on Serbian politics, apart from a hard-core set of nationalists, most Serbs have grown tired of ideology, and simply want to put the war, and Karadzic, behind them.

The poet-warrior, for his part, published verse in hiding, including "The sun is wounding me." It included lines like "Judges torture me for insignificant acts."

Why Karadzic trial may be most important remaining case tried by the special tribunal.