Indian journalists face consequences if critical of Modi's administration

Loading...

| New Delhi

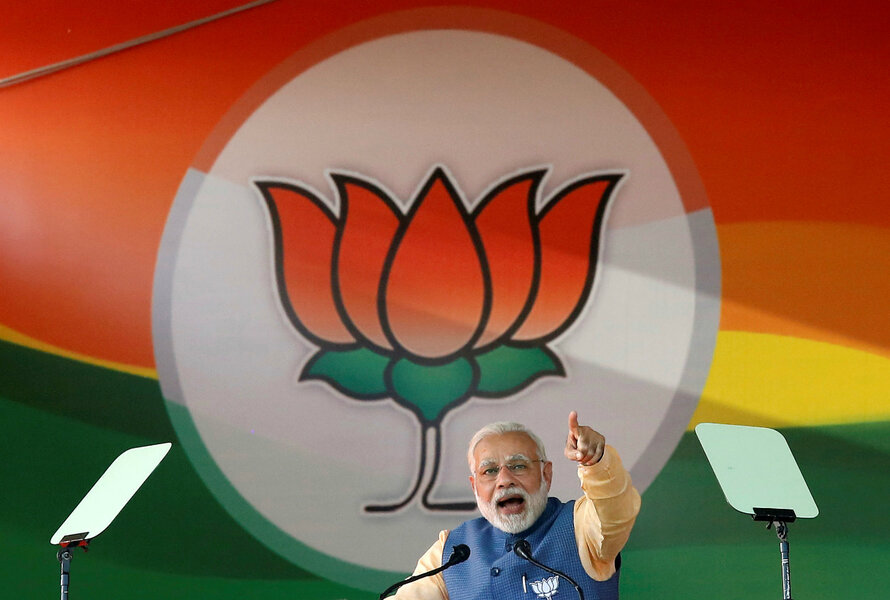

India has constitutional guarantees of freedom of speech and by some measures the biggest and most diverse media industry in the world. But journalists here say they are increasingly facing intimidation aimed at stopping them from running stories critical of Prime Minister Narendra Modi and his administration.

At least three senior editors have left their jobs at various influential media outlets in the past six months after publishing reports that angered the government or supporters of Mr. Modi's Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), according to colleagues.

Some reporters, as well as television anchors, have told Reuters they have been threatened with physical harm, abused on social media, and ostracized by Modi's administration.

In its annual World Press Freedom Index released on Wednesday, the Paris-based Reporters Without Borders said that India was now 138th-ranked in the world out of 180 countries measured, down two positions since 2017 and lower than countries like Zimbabwe, Afghanistan, and Myanmar. When the index was started in 2002, India was ranked 80th out of 139 countries surveyed.

Reporters Without Borders said that "with Hindu nationalists trying to purge all manifestations of 'anti-national' thought from the national debate, self-censorship is growing in the mainstream media and journalists are increasingly the targets of online smear campaigns by the most radical nationalists, who vilify them and even threaten physical reprisals."

The group said that "hate speech targeting journalists is shared and amplified on social networks, often by troll armies."

Spokesmen for the government declined comment on the accusations by journalists. They did not immediately respond to the Reporters Without Borders report.

However, not all Indian journalists believe there is a problem. Swapan Dasgupta, a member of parliament and a political columnist who supports Modi, said the press freedom ranking was "quite inexplicable."

"I don’t believe there has been any shrinkage in the freedom of the media in the past few years," he said in an email.

G.V.L. Narasimha Rao, a spokesman for the ruling BJP, said allegations of media intimidation were far from the truth.

"On the contrary, the BJP has been a victim of the viciousness of large sections of the media that flourished under the patronage of the Congress, left and other opposition parties," he told Reuters in emailed comments. "The unabashed bias of these media against the BJP has not dented our party's political growth."

Some journalists in India say they believe media freedoms are now under even more threat in the run-up to an election due next year. There have been some signs of increasing opposition to Modi's economic policies and to the BJP's muscular Hindu nationalism.

"India is going through an aggressive variant of McCarthyism against the media," said Prannoy Roy, co-founder of NDTV, India's first private news channel.

NDTV, which some BJP leaders have called the least friendly of India's television channels, is being investigated for fraud by federal police. The company has called it a witch-hunt.

The government declined to respond to Mr. Roy's comments.

Sagarika Ghose, a columnist with the Times of India newspaper, said she is viciously trolled for any criticism of the administration.

"The minute I write something, I get droves of hate mail," Ms. Ghose said. "I have had death threats and gang rape threats on social media and also through letters sent to my home. They know where I live."

Ravish Kumar, a news anchor who has been scathing about the government in his program for NDTV's Hindi-language channel, said he has been constantly harassed and threatened by pro-government activists.

"This is very organized," he told Reuters. "They follow me. When I go out to report, a crowd gathers in 10 minutes."

Reporters Without Borders counted instances of Indian journalists being killed because of what they write.

"At least three of the journalists murdered in 2017 were targeted in connection with their work," it said.

Among them was editor and publisher Gauri Lankesh, a vocal advocate of secularism and critic of right-wing political ideology. A member of a hardline Hindu group has been arrested for the murder of Ms. Lankesh, who was gunned down outside her home.

Journalists say that media proprietors, who often have multiple kinds of businesses, are risk averse and can be leaned on by the government.

"Media proprietors are notorious for reading the tea leaves, they get a clear sense of the tolerance level of politicians in power," said Siddharth Varadarajan, who runs a not-for-profit online news portal called The Wire. "Government ministers have coined this word, presstitute, to describe journalists who are unfriendly to them or who don't do their bidding," he said.

Bobby Ghosh, the editor of the Hindustan Times, one of India's premier broadsheets, quit last September shortly after Modi met the owner of the newspaper. At least two senior journalists familiar with the situation said they were told that Modi was unhappy with Mr. Ghosh's editorial policies.

The journalists told Reuters that Ghosh fell out of favor with the government after he launched a webpage called the Hate Tracker, a database of violent crimes based on religion, race ethnicity, gender, or sexual orientation.

The database was taken down in October.

Ghosh declined to specify why he quit the Hindustan Times.

The prime minister's office and the newspaper declined requests for comment on the matter.

A letter published at the time from the government's chief spokesman Frank Noronha said Modi had met the Hindustan Times chairwoman Shobhana Bhartia when she invited the prime minister to attend a conference organized by the newspaper.

"Other related assumptions and insinuations ... are baseless and denied," Mr. Noronha said. "The government is committed to the freedom of the press."

Restrictions on reporting are likely to intensify heading into the election, said Harish Khare, who resigned as editor-in-chief of the widely read Tribune newspaper last month.

"It [the government] will use every resource in its command to pressurize, manipulate, misguide media, or any other voice which seeks to be independent of the government," said Mr. Khare, who was for some time the prime minister's press secretary in the Congress Party government that lost power to Modi and the BJP in 2014.

He told Reuters his relations with the Tribune's controlling trust nosedived after the newspaper published a story exposing flaws in Aadhar, the government's national identity card project.

The newspaper's trust rejected his accusations. "To the contrary, the Tribune Trust gave an unprecedented award of 50,000 rupees [$765] to the correspondent [who wrote the story] in recognition of the work," said officiating editor K.V. Prasad in an e-mail.

"The editor-in-chief's departure came close to the end of the tenure."

This story was reported by Reuters.