Pakistan's political future questioned after the flood

Loading...

| Islamabad, Pakistan

Will the fallout from the worst natural disaster in Pakistan's history result in the downfall of its fragile civilian government?

That question is front and center as the perception grows among Pakistanis that the government response to flooding has been lackluster and insufficient.

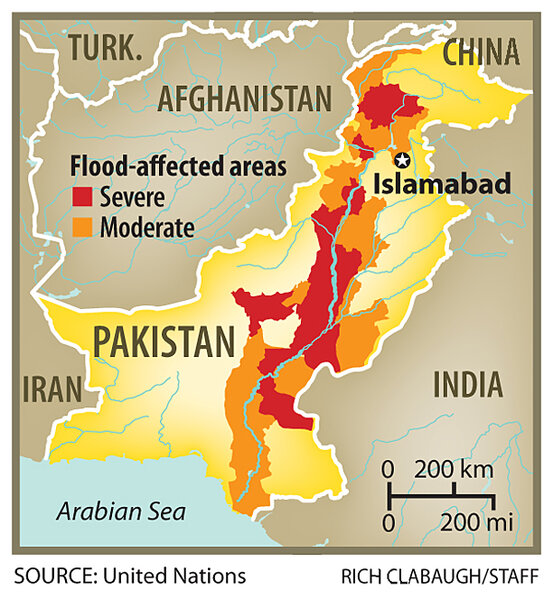

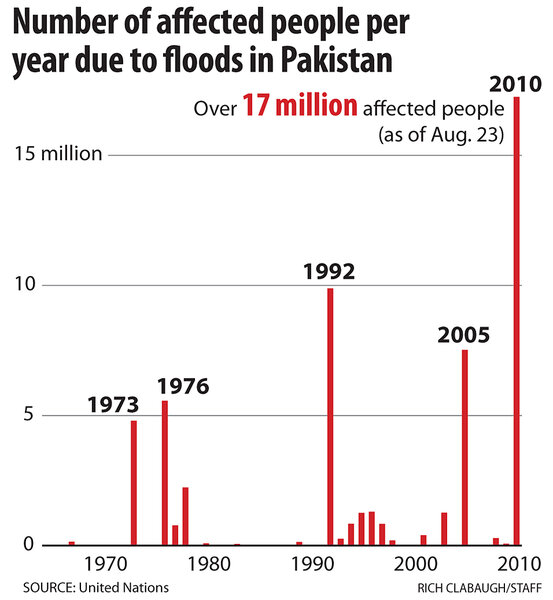

More than 17 million people have been affected by the floods, and about 17 million acres of farmland are under water. Amid the crisis, the military has been out front, driving high-profile rescue efforts with some 60,000 Army troops.

That is turning debate to the question of how best to govern a country that has experienced military rule for roughly half of its 63-year existence. Spurred by dismay over politicians who were slow to address their constituents' needs (and a president who continued to tour Europe as the crisis grew), momentum in favor of military rule appears to be picking up among Pakistan's upper-middle classes – historically the group least likely to favor democracy. "At least the Army gets the job done, unlike the politicians who only seem to care for lining their pockets," says Ali Sajjad, a textiles businessman in the city of Lahore.

Others argue that international disapproval and domestic wariness of the Army after Gen. Pervez Musharraf's military rule, which ended in 2008, will keep a coup at bay. Debate over the political future looks set to continue as the daunting dimensions of recovery from the flood become apparent.

A more functional 'political dispensation' ?

Najam Sethi, editor of the respected Friday Times, recently jumped into the debate, writing that Army chief Gen. Ashfaq Parvez Kayani may wish to initiate a "more functional and stable political dispensation." The way Kayani could go about doing that would be either via a coup, he argued, or by replacing the present administration "with a more honest, efficient, and neutral lot," creating a "national unity" government of retired bureaucrats and experts.

Altaf Hussain, a powerful political leader from Karachi, in late August called upon patriotic generals to take "martial law type action" against corrupt and feudal politicians. Mr. Hussain's Muttahida Quami Movement party is a key ally in the present ruling coalition.

"The drumbeat is a familiar one; you see the same calls from the middle classes for accountability and less corruption," says Badar Alam, editor of Pakistan's Herald magazine, who likens the atmosphere to that of 1999, when Musharraf ousted then-Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif.

This time, President Asif Ali Zardari's decision to continue his diplomatic trip to Europe as the flooding began enraged ordinary Pakistanis.

Though some political leaders, such as the prime minister, have been visible, politicians across the spectrum have taken hits for failing to return to their constituencies quickly after the crisis began.

"The chattering classes have been saying this can't go on, and that Zardari has to be removed," says Ayaz Amir, an opposition member of parliament. "The stock of the government, which was not very high to begin with, has fallen pretty low. Fewer and fewer people are taking Zardari seriously," he says, referring to interviews Mr. Zardari gave to the foreign press that were widely perceived as muddled.

But could the Army handle the responsibility?

Still, says Mr. Amir, the scale of the disaster is such that the burden of leadership may be too much for the Army. "Any government will fall short of what is required or what people expect," he says, "even if we had the most perfect government."

"The Army's profile is going up," Amir continues. "Its PR is going up. When Kayani undertakes a visit, it's much better choreographed, and that creates an impression that the Army is really much more efficient, although we have no tabulated figures on the relief effort taken by the Army or the impact on the overall situation."

He doesn't think the Army would step in. "I think they are pretty happy and pretty comfortable seeing the civilian process bleed like this," he says.

Army takeover could be problematic

Internationally, a military takeover would be viewed adversely and could hurt the fight against the Taliban, says retired Army Gen. Talat Masood, now a security analyst. "It may be possible that if President Zardari continues to make major blunders, like he did while the floods were ravaging the country, that may result in everyone deciding he's had his innings," he says. But, he adds: "The military is already overstretched without having to deal with running the country. Militants would be very pleased if a thing like that happened."

The Army's image took a hit when Musharraf plunged the country into a judicial crisis in 2007. It has begun to improve in the past two years after its moderate success against the Taliban in Swat and South Waziristan. Such hard-won respect isn't likely to be risked so early.

[Editor's note: the original version of this story misstated the year the country plunged into judicial crisis.]

And Kayani, regarded as a consummate professional, probably knows "what the limitations in any misadventure may be," and the international approbation Pakistan could face, particularly from Europe, if the democratically elected civilian government were thrown out.

It is possible that part of the discourse is manufactured by those with an interest in a nondemocratic setup. "The massive devastation caused by a natural disaster is simply being manipulated by wanna-be ministers in a wished-for unelected setup," says Farahnaz Ispahani, a senior parliamentarian from the ruling party and Zardari's spokeswoman.

In the end, Pakistan's military may decide it prefers to remain seen and not heard: "The Army still controls substantial parts of the government in Pakistan; they get to call the shots both domestically and internationally," argues a Western diplomat who asked not to be named.

As evidence he cites Pakistan's ever-growing defense budget and the widely held view that the nation's defense and foreign policy come under the purview of the Army. "When they can get the same results behind the scenes," he says, "why come on the scene?"