New memo reveals Japanese leaders' thoughts on eve of Pearl Harbor

Loading...

| Tokyo

A newly released memo by a wartime Japanese official provides what a historian says is the first look at the thinking of Emperor Hirohito and Prime Minister Hideki Tojo on the eve of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor that thrust the United States into World War II.

While far from conclusive, the five-page document lends credence to the view that Hirohito bears at least some responsibility for starting the war.

At 8:30 p.m. in Tokyo, just hours before the attack, Tojo summoned two top aides for a countdown to war briefing. One of them, Vice Interior Minister Michio Yuzawa, wrote an account three hours after the meeting was over.

"The emperor seemed at ease and unshakable once he had made a decision," he quoted Tojo as saying.

To what extent Hirohito was responsible for the war is a sensitive topic in Japan, and the bookseller who discovered the memo kept it under wraps for nearly a decade before releasing it to Japan's Yomiuri newspaper, which published it last week. Hirohito was protected from indictment in the Tokyo war crimes trials during a US occupation that wanted to use him as a symbol to rebuild Japan as a democratic nation. Hirohito died in 1989 at age 87 after 62 years on the throne.

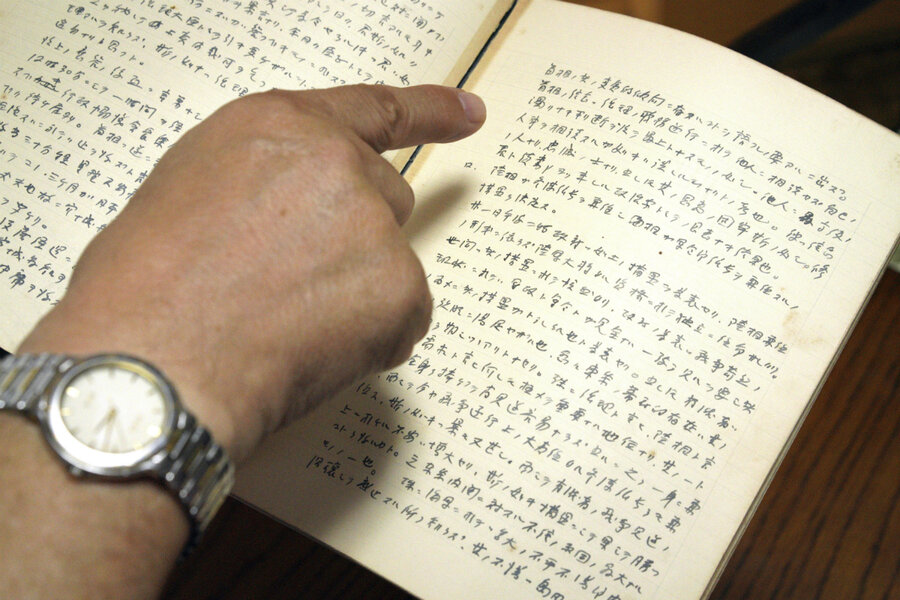

"It took me nine years to come forward, as I was afraid of a backlash," said bookshop owner Takeo Hatano, who handled the document carefully as he showed it to Associated Press journalists. "But now I hope the memo would help us figure out what really happened during the war, in which 3.1 million people were killed."

Takahisa Furukawa, a Nihon University expert on wartime history who has confirmed the authenticity of the memo, called it the first detailed portrayal of Tojo and Hirohito just before the attack. Palace documents have confirmed Hirohito's daytime meeting with Tojo on Dec. 7, 1941, but without elaborating.

The memo supports the view that Hirohito was not as concerned about waging war on the US as was once portrayed, Professor Furukawa said. The emperor had endorsed the government's decision to scrap diplomatic options at a Dec. 1 meeting, and his unchanged position the day before the attack reassured Tojo.

Yuzawa's account portrays Tojo as upbeat and feeling a sense of accomplishment after all the required administrative steps for war had been taken and, most importantly, Hirohito had given him the final nod without asking any questions.

"If His Majesty had any regret over negotiations with Britain and the US, he would have looked somewhat grim. There was no such indication, which must be a result of his determination," Tojo is quoted as saying in the memo. "I'm completely relieved. Given the current conditions, I could say we have practically won already."

His optimism was misplaced. The Pearl Harbor attack killed nearly 2,400 US servicemen and caused major damage to the US Pacific Fleet. Within months, however, the tide was turning. Tojo was blamed for prolonging the war after it was clearly lost, leading to the US atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945. He was later executed as a Class-A war criminal.

Tojo, whose administrative skills and loyalty had won Hirohito's trust, was made prime minister just two months before the Pearl Harbor attack and served in the post for most of World War II.

Furukawa said Tojo's remarks in the memo about his relief at completing the preparations for war support evaluations of him as a good bureaucrat but not a visionary leader. More decisive leadership might have ended the war earlier, he said.

"Tojo is a bureaucrat who was incapable of making own decisions, so he turned to the emperor as his supervisor. That's why he had to report everything for the emperor to decide. If the emperor didn't say no, then he would proceed," Furukawa said. "Clearly, the memo shows the absence of political leadership in Japan."

Yuzawa wrote in the memo that he was "moved and honored to get involved in war preparations at the time of a crucial event that would determine the fate of the Imperial state." He was later promoted to interior minister but turned critical of Tojo's leadership and was dismissed from the Cabinet over a policy difference.

"He is a man of passion and loyalty," Yuzawa wrote of Tojo in a notebook he kept. "But he is so narrow-minded and he has no philosophy as a political leader."

Mr. Hatano, a longtime acquaintance of some of Yuzawa's descendants, received the notebook and other items from the family when they wanted to make room in their apartment. He found the memo folded in half inside the notebook about a year later.

"When I recognized the date, Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, I knew it was something special," he said. He examined it repeatedly to try to make sense of the handwriting and archaic language. "Then I spotted references to the emperor and Prime Minister Tojo."

This story was reported by The Associated Press.