Chinese media falls for phony phone foil story about Trump

Loading...

CNN may get a reprieve as the object of President Trump’s ire, thanks to a serendipitous combination of two of the president’s favorite topics: China and fake news.

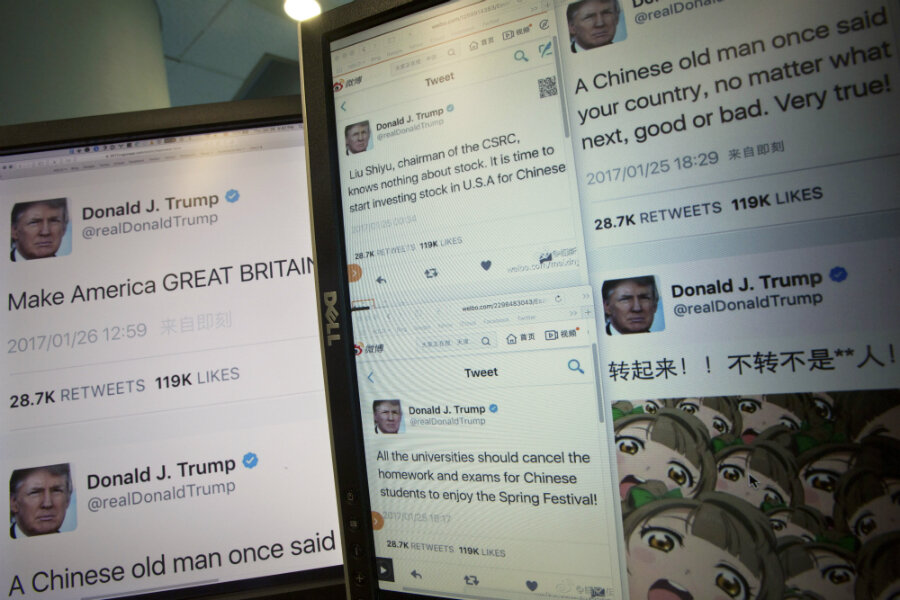

Published Saturday in The New Yorker, comedian Andy Borowitz’s humorous satirization of a paranoid president wrapping phones in tinfoil got picked up Tuesday by multiple Chinese news outlets. The truth had come out by Wednesday, but not before highlighting how easy it is for sarcasm to get lost in translation.

Riffing on the president’s Twitter allegations that former President Barack Obama wiretapped Trump Tower phones before the election, The New Yorker article depicted a paranoid commander-in-chief insisting aids Obama-proof all White House phones with a layer of tinfoil.

“The President, still wearing his bathrobe after what was reportedly a sleepless night, personally supervised the tin-foil installation, sources said,” read a line from the piece, which bears the label “Satire from the Borowitz Report.”

But that didn’t stop Reference News, a Chinese website run by state media Xinhua that translates international coverage, from reporting the joke as serious on Tuesday. Publications that fell for the misreporting included respected outlets such as the business magazine Caijing, as well as news portal Sina.

At least one internet reader, confronted with apparently earnest headlines such as “Trump turns White House upside down looking for signs of Obama: ‘I know he’s still here!’ ” quickly saw through the gaff.

“This was made up and meant to be funny,” one user said, according to The New York Times. “Surprising it was treated as news. Editor, could you be more professional?”

Some may be inclined to blame the miscommunication on Mr. Trump’s tendency to defy convention, but Tuesday was just the latest in a string of incidents where Chinese media mistook comedic headlines for truth.

In 2012, the Communist Party’s newspaper The People’s Daily ran a story naming North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un as the “Sexiest Man Alive.” The American editorial board bestowing this great honor? The Onion, one of the most famous news satire organizations.

Ten years before, the tabloid Beijing Evening News picked up another Onion story reporting that Congress was threatening to leave Washington, D.C., to get a new building, much like sports team threaten departure as leverage to have cities build them new stadiums.

Rumors and conspiracy theories run rampant on the Chinese internet, as they do on the internet at large, occasionally leading to the inevitable misreading.

“Fake news is undoubtedly a serious problem in China, as it is elsewhere in the world,” David Bandurski, editor of the China Media Project at the University of Hong Kong, wrote in an email to The New York Times.

But like Trump, the Chinese government uses the term to their advantage as well.

Last Thursday, the state media reported that recent descriptions of a political activist’s torture were “fake news” made up to gain attention.

They’re "probably borrowing it from Donald Trump's attack on major Western media," Patrick Poon, China researcher at Amnesty International told Reuters.

Rights organizations say the Chinese police often use threats and violence to coerce confessions.

Western media could not reach the detained activist for confirmation, but at least in the case of the tinfoil covered phones at the White House, the truth did win out in the end. Chinese media reported the story as false on Wednesday, and Reference News removed their coverage.

This report contains material from Reuters.