Typhoon Haiyan: Can Philippines build back better?

Loading...

| Tacloban, Philippines

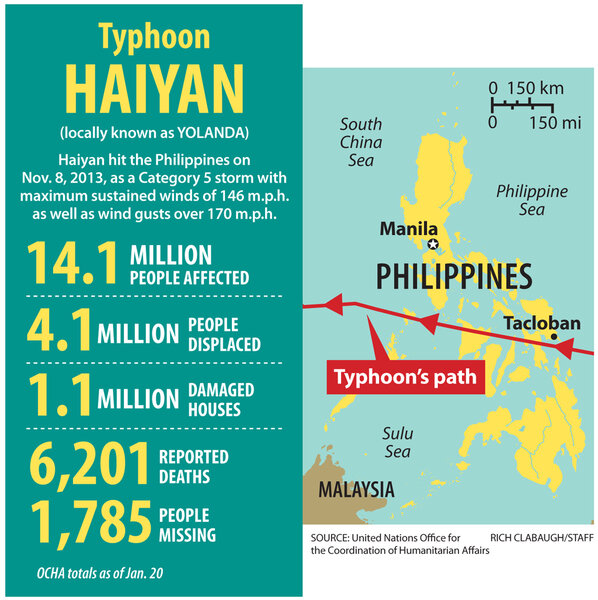

In the desolate aftermath of a typhoon like Haiyan, whose record winds last November killed thousands of people, shattered more than a million homes, and tore up tens of millions of trees, the idea of building back better might sound like an impossible dream, if not a bad joke.

But "building back better" has become a mantra for international aid workers in the wake of natural disasters that have taught them lessons they can use here. And many victims of the recent monster storm here say the goal is an imperative if they are to face the certainty of future typhoons with any confidence.

Right now, across an area the size of Maine, subsistence farmers and fishermen are still scrambling to get any shelter they can over their heads. Tarpaulins from aid agencies, scavenged timber, twisted sheets of old tin roofing, and a few handfuls of nails are all that most of them have at hand as the rainy season sets in. Rice gruel and the occasional canned sardine is all they are eating.

Government officials, in the meantime, are still surveying the scope of the disaster and are occupied with drawing up a recovery program they estimate will cost nearly $9 billion over several years.

There is a chance, though, that the dreadful scale of the destruction, forcing peasant farmers and planners alike to start from scratch, might offer an opportunity for fresh thinking. A silver lining, if you like.

It could be as small as six-inch pieces of two-by-one lumber that a villager can use as roof braces to better secure the roof of his hut against strong winds. Or as big as a new model for the nation's devastated coconut industry, transforming it from a simple supplier of cheap raw export material into a value-adding chain of businesses to create more local jobs and wealth.

Or somewhere in between, like Nestor Villarin's hope that he can harness some of the attention and money that Haiyan has brought to Tacloban to make long-overdue repairs to the city's water pipes, for which he is responsible.

"Now is the best time to do things that should have been done a long time ago," says Mr. Villarin, head of the municipal water department. "Everybody is here to rebuild the city."

"Building back better" can take many shapes. But it faces many obstacles, too, particularly in poor countries that endure most natural disasters and suffer their effects most severely because they are least prepared.

"I haven't seen it happen in many places," says Jesper Lund, the Danish veteran aid worker who is heading the United Nations humanitarian program here as he looks back on a lifetime of dealing with disasters. "If building back better was cheaper, everybody would do it."

Nor is money the only factor. In Haiti, struck by an earthquake four years ago, recovery has been stymied as much by the breakdown of family and other social relations as by the massive scale of the damage. And even in wealthy Japan, which has the financial means to build back better, a slothlike bureaucracy has hindered plans to make that goal a reality for many of the victims of the 2011 tsunami.

And in countries where citizens do not trust their rulers, they are unlikely to have much faith in official advice to wait a little longer in meager emergency shelters while better permanent solutions to their needs are organized.

But if there is one key lesson aid workers have learned from past disasters, it is that nobody can "build back better" better than the victims themselves, deciding what they want and how to get it. Outsiders can help, but in the end it comes down to the people who have to remake their lives. And in Tacloban, there is no shortage of local initiative.

Loss creates a new entrepreneur

When volunteers from a Taiwanese Buddhist charity visited the shoreline district of Anibong soon after its squatter shacks had been washed away by the typhoon-whipped storm surge, handing out money to survivors, most of the distraught recipients spent the largess on food, clothes, and other immediate needs.

Evangelina Bacoy, however, thought one step ahead. She set most of her $270 gift aside, and then used it a month ago to open a small roadside store.

A middle-aged homemaker and mother of three children, Ms. Bacoy had never done anything like this before. She had always relied on the wage that her husband, a painter-decorator, used to bring home each week. But now her husband is jobless, fortunate to find a few days' work at a time cleaning up the storm debris. She earns twice as much as he does, selling soft drinks, canned sardines, biscuits, cigarettes, soy sauce, cooking oil, and other simple goods from what used to be her front room.

"It's a big challenge," she says. "But I enjoy it, and it helps with a lot of our family expenses."

Most of the Bacoys' home was swept away by the tidal wave. Bacoy's store is overshadowed by a hulking cargo vessel, carried inland by that wave and stranded 50 yards from the shore. Happy to be alive, she and her husband scavenged timber and sheets of plywood to knock together a stilted platform and furnished it with a mattress and a couple of armchairs she found among the debris.

A generous length of sturdy tarpaulin serves as their roof. "I found that on the street," she explains with an embarrassed giggle. "Some looters had taken more than they could carry, and they left it behind."

Bacoy has no idea how long she will be living like this. She has heard rumors that the city government will not allow people to live close to the shore anymore for fear of future storm surges, but nobody from the government has come to tell her that, or anything else about where she might be moved to after having made her life here for many years.

That does not dampen her ambitions. Her priority now, she says, is to "focus on making sure this store works well. I think I'll make it bigger if I can. And I'll keep running it as long as I need to."

A new aid model using cash handouts

As recently as 10 years ago, handing out the sort of cash that Bacoy got was anathema to most Western aid groups. Members of the public who donated money, and the agencies that used it, were too afraid it would be stolen or wasted.

But the relief effort in the Philippines is pointing a new way ahead. Aid workers say they are now using cash handouts as a more flexible, cost-effective, and empowering way to help typhoon victims build back better.

In the past, says Tariq Riebl, humanitarian response manager for the Britain-based aid-and-development group Oxfam, "the inclination would have been to just go in and dig latrines" for people who needed them.

Here, however, Oxfam is planning to hold workshops and educational sessions to explain the benefits of proper sanitation, and then to give people money to pay masons and carpenters – if they want to – to build them a latrine.

That way, says Mr. Riebl, "local people understand the need, they use their own free will to get one, they put their money where their mouth is, and artisans who build them well can develop a sustainable business.

"It takes more time, and it's more onerous, but the point is that we are instigators of ideas rather than first implementers; it's more sociological than technocratic."

This novel reliance on market mechanisms and small-scale entrepreneurs will not necessarily work everywhere in the world. In the very poorest countries or war-torn regions where transport is next to impossible, it is too expensive for local artisans to find building supplies.

But in the Philippines, a middle-income nation with a vibrant entrepreneurial economy, says Riebl, "there are a lot of things working in favor of this new approach."

Storm victims drive their own recovery

Building back better is not hard when what you are talking about is a simple four-walled hut on stilts with a corrugated tin roof, which is all Allan Copioso has ever lived in. But even so, it takes know-how and money.

Mr. Copioso, a young father of three who scratches a living from his rented rice paddy and a few coconut trees, now has the know-how. So when he gathered up the bits and pieces of his house that the typhoon had scattered, he put them together in a new way.

He made the pitch of his roof steeper and shortened the eaves, so that the wind will not get under them so easily. He nailed small bits of wood between the rafters and the roof supports to brace them. And he used tie wire, not just nails, to secure the corner posts of his home to the pilings beneath.

This is not rocket science, agrees Efren Mariano, an engineer working with CARE who suggested these tips and others to Copioso and his neighbors in the rural village of San Miguellay, a cluster of a hundred or so simple homes 20 miles inland from Tacloban. "They are small pointers, but they will strengthen the house," says Mr. Mariano.

Mariano is in charge of a project to train local carpenters to help San Miguellay's villagers rebuild their houses; 77 of them were wiped out, 21 were partially damaged, and only 8 withstood the highest winds recorded on land (195 miles per hour).

CARE is giving out building materials, but more important than the hardware, says Mariano, is the way the villagers themselves are using it.

He has worked with the village council to organize householders into groups, assigned a local carpenter to each cluster of homes, and held a meeting during which he asked people why they thought the few surviving houses were still standing and what they could learn from them.

"The most important element in what we are doing is community involvement in the process," says Mariano, "so they understand why they are doing these things."

That doesn't sound like rocket science either, but involving people in their own recovery from natural disasters is far from automatic.

When former President Bill Clinton came to write his final report as special UN envoy for tsunami recovery, three years after the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, he made his first "key proposition for building back better" the simple guideline that "governments, donors and aid agencies must recognize that families and communities drive their own recovery."

Though that may seem self-evident, he wrote, "the experience of the tsunami only underscores the reality that rhetoric in this area has yet to translate fully into practice."

Having rebuilt his home by himself, Copioso says he is clear how and why the improvements he has incorporated will make it stronger.

But he hasn't followed all of Mariano's counsel; he wanted a slightly bigger house, so the tin roofing sheets that CARE provided were insufficient. He used a few old sheets as well, but that meant he did not have enough roofing nails to secure them as well as he should have.

Nor does Copioso have enough money to buy the split bamboo he needs to put up walls. For the time being he is making do with blankets stretched around the outside of his hut, and a sheet hanging across the middle of it to provide a private sleeping area for the family.

So his house is not really better than before, yet. "But when I find the money I will finish it," he says.

"Even if people rebuild in a way that is not better, if they learn how to do it they will be able to do so when they have a livelihood," says Peter Struijf, program manager for Oxfam, which is also spreading the word here about simple, safe building tips. "It's about giving people the tools and the knowledge they need."

Eventually, Copioso hopes, he will have not only the know-how but also the funds to use it fully. "Then perhaps the next storm will only damage my house, not wipe it out completely," he says.

As ambitions go, that may not be much. But it is better than the nothing he was left with this time.

Rebuilding conflicts with land rights

Ramil de los Reyes, kneeling with a carpenter's square in his hand on new floor joists a few feet above a squalid, waterlogged jumble of garbage, old clothes, wooden debris, and concrete rubble, is also building a new house.

Which is odd, because he is only a few yards from the shoreline in Magallanes, a Tacloban slum, and he has heard on the radio that the city government has banned the construction of dwellings within 45 yards of the sea in case of another storm surge one day.

"I don't have a choice," he explains. "I have nowhere else to live."

That is a common refrain among his neighbors, all illegal squatters rebuilding within a few feet of each other on land that belongs to the government by eminent domain. Many of them, like Mr. de los Reyes, are putting up new homes on the plots they have always occupied. During a brief respite between torrential downpours, the air is loud with the sounds of saws and hammers.

De los Reyes works with accuracy and skill. He seems to have done this before. He has, he says, in 1986, when a storm knocked down his original home. Then typhoon Haiyan destroyed what he had built, so he is starting over.

Until he finishes, he and the eight members of his extended family who live with him are camping out in a nearby school that has been commandeered as an evacuation center. He has heard rumors that the authorities plan to soon move homeless squatters into "bunkhouses" – barracks-like emergency shelters – but he won't go, he says.

He complains that they are cramped, unsafe, and, worst of all, miles away from the sea.

"I sell fish," he says. "I need to live near where I work."

De los Reyes and tens of thousands of people like him living up and down the storm-stricken coast of the central Philippines will not find it easy to build back better. Their fate is tangled up with the complex questions of land rights and land use that so often beset poor people in developing countries and that are not often answered in their favor.

At best they might be allowed to stay where they are. But there is also the risk, warns Mr. Struijf, "that the government might say 'good riddance.' " Empty land by the sea in a tourist region such as this where only commercial property, not housing, will be allowed, could be valuable, Struijf points out. After the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, he recalls, washed-out fishing communities in India and Sri Lanka were evicted to make way for developers.

In the Philippines, says Steven Rood, an expert on the country who works in Manila for the Asia Foundation, "there is a vast morass of laws and expectations" that are likely to conflict with each other. "There are bound to be protests," he predicts.

Across the bay from Magallanes, in another devastated squatter colony called San Jose, community leader Emelita Montalban says she has been trying unsuccessfully for years to convince the city government to buy the private land on which most of her neighbors live illegally, so as to give them security of tenure.

Without legal rights, they are vulnerable.

And where would the fishermen and others living near the sea, in newly declared "no build" zones, be sent? Bunkhouses, often shoddily built and offering only the barest of facilities, may have been designed as temporary housing. But in other parts of the Philippines people displaced by earlier natural disasters are still living in such accommodations years after they moved in.

That is because it takes a long time to build permanent housing. In Tacloban alone, says Mayor Alfred Romualdez, as many as 8,000 families need rehousing. Even if he had enough land near the sea to build 8,000 homes, which he doesn't, and could build 20 houses a day, which he says is unrealistic, it would take more than a year to resettle everyone.

"This sort of thing cannot be done in a couple of weeks," he says.

Given that sort of uncertainty, de los Reyes is perhaps wise to build what he can where he can, whether or not it is legal, and even though he is hardly building back better. "I have lived here since I was born," he says. "This house may be temporary … but I am not very confident about what the government tells us. There is no guarantee of anything."

Foreign aid slow to inject cash

Building back better does not have to be expensive, but when it comes to anything more complex than a family home, it does cost money. And money is in short supply here two months after Haiyan.

Everybody complains about it, from the lowliest squatter by the beach to the head of the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, the umbrella organization overseeing relief and recovery here.

International donors have come up with only 42 percent of the $788 million the UN says it needs to help storm victims get back on their feet over the next year. That means that many plans to rebuild houses, or launch job-creation schemes, or just keep people healthy have been put on hold.

And most ordinary Filipino victims who have lost their rice seeds or their jobs are broke. They are waiting to hear what, if anything, their government will offer them to rebuild their lives, and in the meantime they are scraping by on charity. Monitor interviews with scores of people over a week in and around Tacloban found no one who said they had enough money to restore their life to its former standard.

The government, meanwhile, is going to have to spend money checking and strengthening all the public buildings – hospitals, schools, and offices – that were damaged.

"Building back better is not going to be cheap," warns Ramesh Subramaniam, deputy head of the Southeast Asia department of the Asian Development Bank in Manila. "It could be 30 or 40 or 50 percent more expensive than replacing what was there before." Costs, he adds, are "a big concern."

Seeing opportunity in a clean slate

One aid agency that does have money is Oxfam. It is spending some of that money on the first steps to revive the ravaged coconut industry on which almost all farmers in this region of the Philippines have depended, at least partially, for their livelihood.

The immediate job at hand, says Ditas de la Peña, head of a farmers' cooperative in the village of Anahaway, is to clear as many as possible of the 120,000 fallen coconut trees in her district – 70 percent of the original total.

If they are left to rot they will harbor dangerous pests, and until the trunks are gone nothing can be done to replant the groves.

So Oxfam has donated three chain saws and a table saw to Ms. de la Peña's cooperative, and to five others like it. The co-ops buy the trunks from farmers, which provides them a little cash to start rebuilding their homes or to buy rice seedlings. Then they sell the lumber they cut to anyone who can afford it – international agencies or private individuals – for their own construction projects.

That should provide seed money for the plans de la Peña has to improve living standards for her co-op members, who have traditionally relied on coconuts and rice for their meager income.

"We can plant fruit trees like banana, mangosteen, durian, and pomelo," she says, to provide income for the years it will take for new coconut seedlings to mature and bear fruit. "And vegetables and root crops. It's a challenge, but I am hardworking."

Intercropping is not traditional here, but there is no reason it cannot be done, say agricultural experts; government planners are talking about introducing coffee and cacao, too.

"The fact that the slate has been wiped clean might encourage transformation," suggests Mr. Rood.

It also offers a chance to regenerate the region's aging coconut rootstock. Local farmers have long been reluctant to adopt new varieties, even faster-growing and higher-yielding ones, preferring the old trees that they know.

"I clearly see an opportunity now … to organize communities to set up nurseries of hybrid seedlings," says Rajendra Aryal, head of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization in Manila.

Equally important is the prospect that the coconut industry might be revived along different lines that would bring more prosperity to the countryside.

Until now, farmers have sold their coconut meat to mills that extract crude quality oil and sell it abroad. Nobody made much money from that. "There are no industrial jobs and little value added," says Struijf. "Why build back the same? What you want is better opportunities for more people to earn more money."

The Asian Development Bank is thinking along the same lines, says Mr. Subramaniam. "We are giving advice and money to maximize the value chain," he says. "We are bringing together small businesses and financial institutions to see how they could make products from the fruit, like cookies, virgin coconut oil, or skin-care products. We see huge prospects for reviving the industry."

Disaster inspires higher standards

This sort of thing sounds ambitious and it doesn't happen often, but there are precedents.

In Ethiopia, for example, repeated droughts have spurred authorities to find ways of making seminomadic cattle herders more prosperous. They have improved veterinary services and built fattening pens at ports from which the animals are exported to Saudi Arabia, making them more valuable. The next step will be slaughterhouses and meatpacking plants, adding more to the local value chain.

In Rwanda, President Paul Kigame used the trauma of genocide to shock his country into rebranding itself as a high-tech hub for Africa.

And at a simpler level, aid workers point to many places where disasters paved the way for improvements. In the Indonesian province of Aceh, where tens of thousands died in the 2004 tsunami, newly built roads will offer residents swifter escape if such a catastrophe befalls the region again. In Pakistan, since widespread floods in 2010, dams have been built to higher standards. In New Orleans, Katrina prompted the authorities to strengthen levees. Repeated floods in Mozambique during the 1990s led the government to implement proper disaster response plans.

"Disasters do offer an opportunity to change direction," says Peter Walker, head of the Feinstein International Center at Tufts University in Somerville, Mass., which specializes in disaster research.

Whether people and governments take such opportunities depends on many circumstances – social, political, economic, and personal.

Sometimes they must be offered quickly, says Mr. Lund, the UN official in charge of relief efforts in Tacloban: "You don't have time to convene working groups. People want to rebuild their homes right away."

Sometimes they must be offered slowly, especially when it is a matter of how disaster victims are to earn their living. "When you have just lost everything," Lund says, "you need to be taken carefully by the hand" to explore possible new livelihoods.

But either way, insists Timo Lüge, who helps coordinate the aid agencies building shelter for Haiyan victims, "we have to help them build back safer, or else, when the next typhoon hits in two years' time, we'll be back."