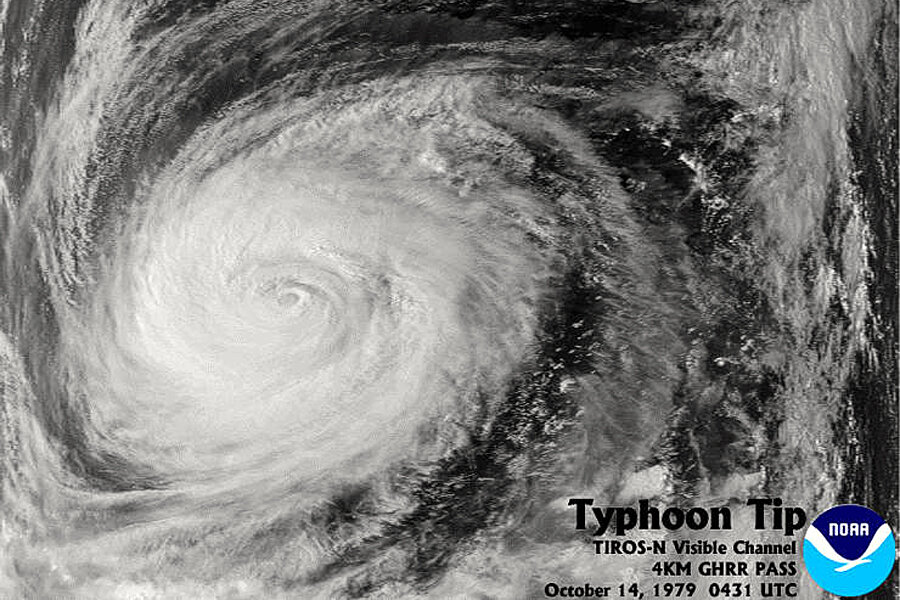

The US National Weather Service considers 1979's Typhoon Tip to be the most powerful cyclone ever recorded. On Oct. 12 of that year, a US government Hercules reconnaissance plane flying out of Anderson Air Base in Guam recorded winds of 190 miles per hour from inside the storm, and at its height the typhoon was roughly 1,350 miles across – about the distance from New York City to Lincoln, Neb. That same day, the pressure at sea level beneath the storm was at 870 milibars, the lowest ever recorded. (Low pressure helps generate high winds). Bob Korose, the pilot of the Hercules that day, described the wind's effect on the plane:

"Generally you just go in as straight as you can, unless you’re able to take advantage of a weak spot in the typhoon," Korose told the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Log in 1998. But Typhoon Tip was a different beast from usual. "“It’s a solid wall cloud, so there’s no easy way in. As you head for the eye, you constantly have to make corrections for the winds. You’re getting blown sideways at 150 m.p.h., or even more than that, so you have a lot of correction. In other words, the nose of your aircraft isn’t pointing to where you are going. You see on the radar that the eye is right straight ahead of you, but actually you point off to the left side as you’re going in because you have such a drift to the right from the crosswinds spinning into the storm."

The good news about Tip is that it missed Guam and had weakened by the time it made landfall on the southern Japanese island of Honshu on Oct. 19. Still, the storm claimed the lives of 42 people ashore in Japan and 44 fisherman at sea.