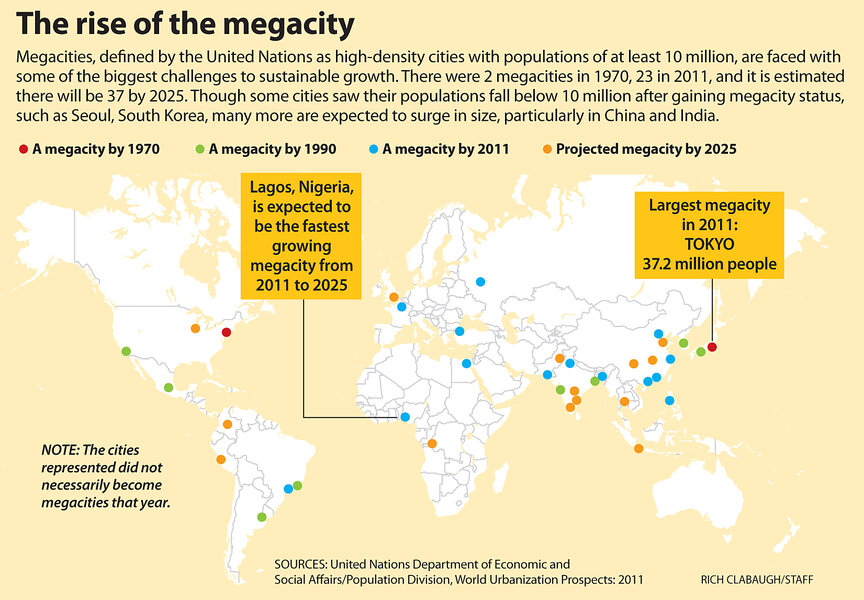

Rio+20 challenge: seeking sanitation in the slums of Lagos, Nigeria

Loading...

| Lagos, Nigeria

With his briefcase and pointed animal-print shoes, Godfrey Achionye looks every bit like the popular actor that he is from Nollywood, Lagos's famous film industry.

But at home, Mr. Achionye must share a squat toilet and bucket bath with three other families. To get to work, he navigates sewage-flooded streets in Ajegunle, Lagos's largest slum, which offers all-important proximity to the hectic city's economic opportunities but little in terms of proper shelter and sanitation.

Just crossing the road is hard work. Residents and visitors hop from rock to rock, walk along stubby brick walls, or jump over pools of black water that flow into the streets from open sewers. On one street, residents tired of sinking their shoes in garbage-filled mud made a trail in the road, using thick sponges, plastic bags, and other refuse to create a surface to walk on.

For a neighborhood that several million people call home – no one knows the exact number – Ajegunle remains largely cut off from basic infrastructure, like the running tap water Lagos's elites take for granted.

And yet, Ajegunle is just one of many such slums that 70 percent of Lagos's population, and, indeed, even part of its middle class, call home.

As more and more Nigerians flood into Lagos in search of jobs and opportunities, the sanitation system is badly under strain. Without improvements, risks of disease increase. Already Nigeria has been hit by several cholera outbreaks, claiming thousands of lives.

Poor sanitation is the main cause of outbreaks like this in a country where 33 million people lack access to toilets. Human waste is out in the open and can contaminate water sources.

Diseases can be carried in human waste, and their top casualties are babies and toddlers. This contributes to Nigeria's high infant mortality rate.

For some, a starting point is simply raising the issue of sanitation, which has long been taboo.

"This habit of doing in public what ought to be done in private strikes me as pointing to a much deeper cultural crisis," US-based Nigerian academic Okey Ndibe wrote last year in a column titled "Nigeria As One Open Toilet."

Nowhere is this problem more stark than in the commercial hub of Lagos, where city officials struggle to meet the needs of the millions of people they are aware of, not to mention the untold millions who don't get counted by census workers, and the nearly 600,000 who keep arriving each year. So far they have bumped up the population to an estimated 11.2 million.

Some Lagosians deliberately live off the grid, while others, including middle-class people like Achionye, desperately want to get connected to sanitation services but are told they must wait.

For Lagos state Gov. Babatunde Fashola, credited with improving several parts of the city, the slums are hard to penetrate, and change comes slowly. His administration has started working on creating passable roads in slums, but many remain in bad shape. The government has also demolished illegal structures built on sewage passageways, but that led to the displacement of thousands of people, highlighting a challenge of working in the slums. For the poor, the demand for urban housing creates a scramble so ruthless that, for many, a toilet and a bathroom – even shared – is a luxury.

King Godo, a Lagos-based reggae singer, can't afford to pay rent, so he's built a bamboo cabin that he has covered with tarpaulin near the beach. When the rains come, he buys more tarpaulin for the roof and plastic sheets to cover the rest of his home. Squatting on land in a shack allows King Godo to spend what little money he earns on producing more copies of his album.

A lack of sanitation is the price he pays to accomplish his dream of success, he says.

Cars and buses are banned from the roads from 6 a.m. to 10 a.m. on the last Saturday of every month. Lagosians are expected to clean their homes while government workers clean the streets. The initiative provides jobs, and residents say it makes the city feel a little cleaner.

Though toilets, or the lack of them, is rarely discussed, it's not because people aren't bothered by sanitation problems. Some people are not only breaking the taboo, but also turning this need into a business opportunity.

The late entrepreneur Isaac Durojaiye, nicknamed Otunba Gaddafi, was famed for starting DMT, a mobile toilet company. He tried to make toilets more accessible.

DMT's blue and red pay-for-use portable toilets dot Lagos today, but progress of any kind always seems to reach the city's dense slums last, leading people like Achionye, a father of four, to pin their hopes on the next generation.

"The buildings may not be fantastic," Achionye says, "but you'll find that every parent in Ajegunle, despite the little resources, is trying to make sure that the children have better lives."