Demystifying Pluto: What scientists hope to learn

Loading...

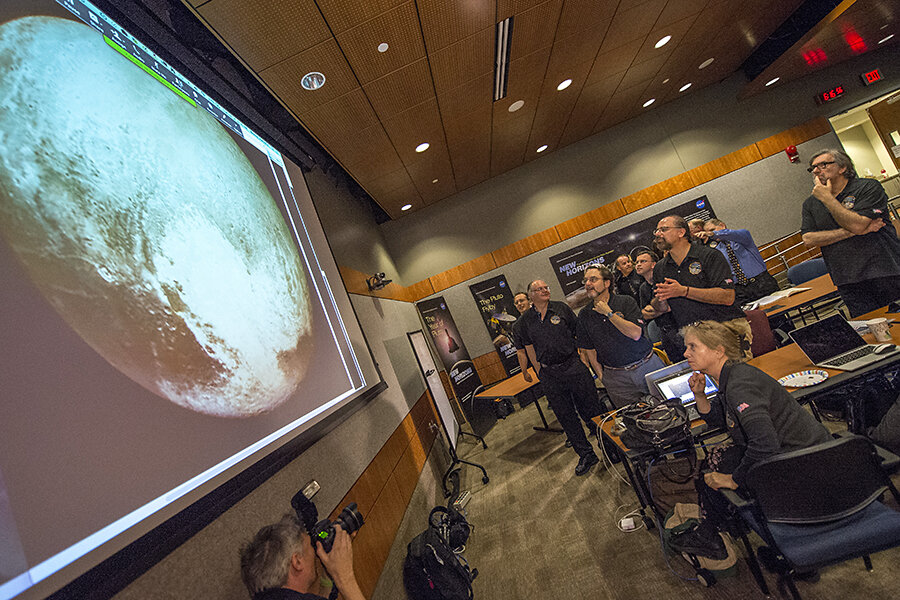

Scientists will soon get their closest look yet at Pluto, after a NASA spacecraft gets within record proximity to the dwarf planet.

The spacecraft, aptly named New Horizons, has traveled 3.3 billion miles over nine and a half years toward the most distant planetary body ever explored, on a mission to take photos that will be sent to Canberra’s Deep Space Communication Complex (CDSCC), a tracking station located in an Australian valley.

"It's very exciting because we have never ever visited Pluto, either by robots or man missions because it is so far away," CDSCC Director Ed Kruzins told Reuters.

New Horizons, the fastest spacecraft ever launched, will get within 7,800 miles of Pluto Tuesday evening, and will be at its closest for about 24 hours. Mr. Kruzins said Pluto is the planetary body we know least about, and discoveries could shed all-important light on the origins of the solar system.

"There's a feeling among scientists that Pluto probably will tell us what the early solar system looked like and it's now locked in deep freeze and maybe it will tell us what we once were, a long time ago," he said.

Though New Horizons has yet to reach peak closeness, it has already delivered information Alan Stern, a planetary scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo. and the mission's principal investigator, called "a gift for the ages.” The Christian Science Monitor’s Pete Spotts wrote:

Even seemingly mundane measurements, such as a new, more-accurate determination of Pluto's size – now pegged at 1,473 miles across, at the high end of estimates that have ranged from 1,429 miles to around 1,491 miles – carry import.

The new size, combined with long-established, precise measurements of Pluto's mass, yields a dwarf planet a bit less dense than previously estimated. That means its interior contains more ice, versus rock, than previously estimated. This change has implications – yet to be worked out – for the process that formed the binary-planet system as well as for the chemistry of the disk of dust, gas, and ice that encircled the sun and provided the building blocks for the planets [and] their moons, Stern explained.

The spacecraft’s most important discoveries will not be made overnight, though. CDSCC will receive a message from New Horizons Wednesday morning if Tuesday’s mission is successful. Data will then start being processed at a rate of four and a half hours per piece of data. Complete transmission will take fifteen months.

The mission may also be compromised if the spacecraft comes into contact with any floating debris. Because New Horizons will be traveling so fast – 36,039 miles per hour – the smallest piece of debris could be extremely damaging.

"Even a grain of sand would cause significant damage to the vehicle," Kruzins said. “It would be like being hit by a brick at 70 kilometers per hour.”

This report contains material from Reuters.