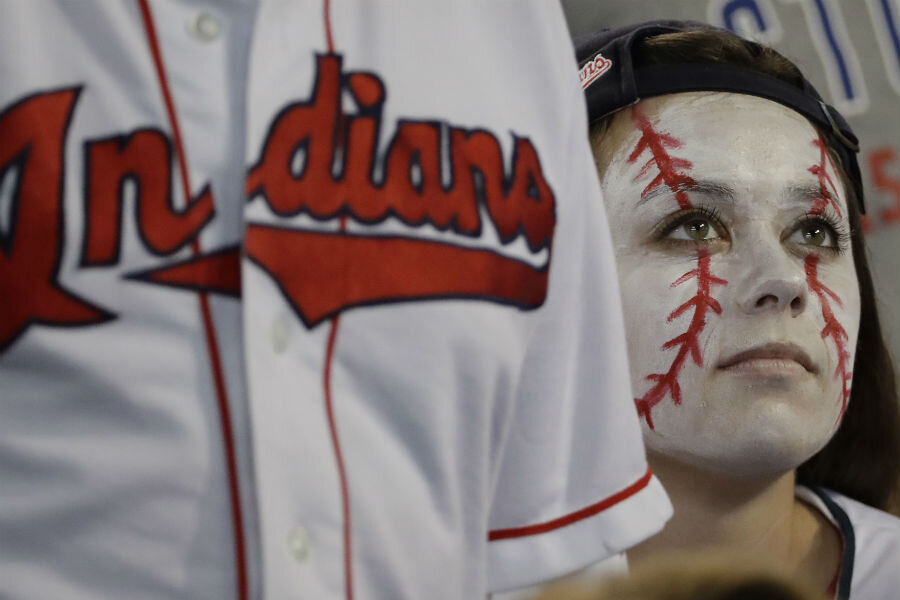

Why Cleveland Indians’ championship merchandise will be destroyed

Loading...

You lose the World Series, your team’s apparel ends up giving someone in a developing country something to wear. That’s how it worked for a while, anyway.

Major League Baseball is breaking with its tradition of donating clothes celebrating the victory of the wrong team, reported ESPN on Wednesday. Instead, licensed gear commemorating the Cleveland Indians’ victory-that-never-happened in the 2016 World Series is going to be destroyed.

The point is to “protect the team from inaccurate merchandise being available in the general marketplace,” MLB spokesman Matt Bourne told the network.

But the move raises questions as to how the league’s incentives might have changed between now and the mid-2000s, when the MLB joined the other three biggest US professional sports leagues in donating losing-team clothes to charities such as World Vision, which distributes them to people in war-torn or developing countries. It also might resurface questions about how valuable the practice ever was.

Here’s one theory: The MLB might suspect that the apparel has a kind of ironic cool that would make it a choice item for collectors on the black market.

“We’ve lived through enough cycles of production of this material that we know it’s out there, and we know it’s donated,” says Robert Boland, director of Ohio University’s sports administration program. “There may have been interest.”

In other words, MLB was worried that Cleveland Indians clothing sent overseas as a donation might find its way back and be sold to fans in Cleveland.

“There may be interest in Cleveland, in particular, because of its long championship drought,” Mr. Boland tells The Christian Science Monitor. “I could see people in Cleveland wearing this in spring training and through the season.”

World Vision says its collaboration with professional sports leagues was born of legal proceedings that saw unlicensed gear confiscated and donated to them. The leagues came calling later, after the group proved it was able to place them "with recipients in extreme need without interfering with the marketplace and while also protecting the branding", senior corporate communications leader Cynthia Colin told the Monitor.

"The primary concerns of the leagues have always been: distributing the product directly to recipients who would be impacted by receiving a new article of clothing, while also protecting their branding and avoiding any possibility of creating a secondary market," said Ms. Colin in a statement.

Given the long odds faced at one point in the series by the Chicago Cubs, who overcame a 3-1 deficit, there’s likely no small number of T-shirts, hats, and other apparel sitting around. One custom printing company in Columbus, Ohio, reportedly printed up nearly 20,000 T-shirts heralding an Indians’ victory.

As Tom A. Peter reported for The Christian Science Monitor in 2007, when the Chicago Bears shelled out $2.5 million for a silk-screened load of unhappy memories after they lost in the Super Bowl, corporations can get tax credits for charitable donations when they donate clothes.

Jim Fischerkeller, World Vision’s director of corporate engagement, told ESPN that he hadn’t heard of World Vision-distributed MLB gear finding its way back to North American markets.

But Boland says for certain teams, those bitter mementos can become a little like the 1909 Honus Wagner baseball card printed by a tobacco company before the early baseball legend ordered them to remove his likeness – a card that sold for $3.12 million in a September auction.

“You don’t want material that’s a kind of fluke to be out there. Its existence sort of undermines the equality of the winners’ material. And it has larger value later as a collectible.”

That might be enough to outweigh the benefits of a minor public-relations burnishing, particularly as the practice of clothing donation has drawn scrutiny from foreign-aid experts, who say it can dump clothes on people who don't really need them, and damage local manufacturing in the process. World Vision, for its part, says its clothes distribution is just one prong of its more comprehensive development projects.

“Many of these kids have never seen something brand new,” the group’s corporate relations officer Jeff Fields told a CBS affiliate in Pittsburgh in 2012. “They’re living in torn clothing, shoes that are ripped, so when they get something brand new from someone far away, they are so appreciative. It really is life-changing for them to receive that.”