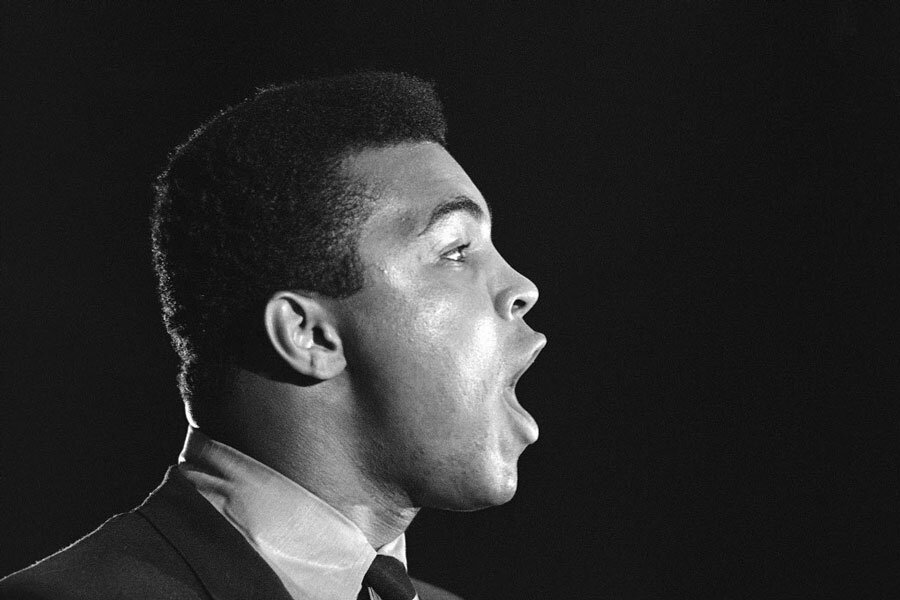

Athlete as moral crusader: Is the Muhammad Ali model lost?

Loading...

| Boston

There are four people in the world Kilbert Pierce says he’d like to have been able to meet, shake hands with, and thank. One is Muhammad Ali.

And it isn’t just because the boxing icon, who passed away last Friday, inspired Mr. Pierce to become a boxer himself. Pierce, now a trainer at The Ring boxing club in Boston, says he was inspired by “the full monty” of Mr. Ali, specifically everything he did outside the ring.

One of his favorite Ali tapes, for example, isn’t of a fight. It’s of Ali talking to white college students during his three-year ban from boxing, a ban imposed after he was convicted of dodging the Vietnam War draft. (That conviction was later reversed unanimously by the Supreme Court.)

“They were firing questions at him, and he had an answer to everything,” says Pierce. “He wasn’t some ... boneheaded athlete. He was smart.”

Leaning back in a chair in The Ring’s air-conditioned office, he shakes his head. “The athletes today, everything is ‘me, me, me,’ ” he adds. “I think money has gotten involved. There’s too much now. I just think everything is money, money, money.”

He is not the only one who thinks the model Ali epitomized has waned. Yet in some ways, it’s a testament to this heavyweight’s enduring legacy that Pierce is voicing this view – and that so many around the world are remembering Ali as prayer and memorial services are held Thursday and Friday in his home town of Louisville, Ky.

Ali, perhaps more than any other athlete of renown, adopted political and moral activism as an essential part of his public life. And Ali’s embrace of Islam – which led him to shed his “slave” name of Cassius Clay – was part of a public stand for black pride and a demand for black respect at a pivotal moment in the civil rights era.

Add in his boxing prowess and braggadocious style, and it is perhaps little wonder that no athletes today are approaching his stature as an athlete so publicly engaged in politics.

But why aren't more of them trying?

Some are. A boycott by football players at the University of Missouri last year over racial issues brought down the school's president. But no single figure across the American sports landscape comes close to Ali.

Where is today's Ali?

In some ways, times have simply changed from his era of upheaval, when black Americans in the South faced not just Jim Crow discrimination but also lynchings. Moreover, athletes also are never cut from a common personality mold. And as Ali himself showed, none are paragons of unalloyed moral perfection.

But, even as some sports stars do take public political stands today, many observers say they could do more.

“Most athletes, especially star athletes, seem more interested in staying quiet and collecting checks,” says Maurice Hobson, an assistant professor of African-American studies at Georgia State University, who played college football for the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Today’s athletes grew up in the Michael Jordan era, experts note, when the Chicago Bulls star continually refused to take political stances – reportedly telling a friend once that “Republicans buy sneakers too.”

And Mr. Jordan’s mantra of brand-over-belief may have only grown as professional sports have become more lucrative. More money – in salaries and endorsements – means more to lose, and athletes have admitted that the financial risks of being politically outspoken are too high for many.

“It’s just the society we live in,” Andre Iguodala, of the National Basketball Association's Golden State Warriors, told the Fresno Bee. “It’s really tough, because guys might think they’re going to lose their situation. The way society says, ‘If you follow these guidelines and walk a straight line, you’ll be taken care of financially.’ ”

The cost of speaking out

Chris Kluwe is one professional athlete who says he has been victimized for not toeing the line. The former National Football League punter claimed in 2014 that he was cut from the Minnesota Vikings roster for publicly supporting same-sex marriage. In an interview with ThinkProgress, he said that professional football teams have taken on “a very corporate mentality.”

“We have this broad business, and we want to appeal to as many people as possible, so we’re going to try to not offend anyone,” he told the site.

“You’re made aware of that as a player,” he added. “Teams are very much aware of that brand awareness and they want to do everything in their power to make sure it’s not rocking the boat, so that as many people as possible will come watch football games.”

Athletes now prefer to be active in less confrontational ways – like giving to charities, funding scholarships, and investing in poor communities, says Johnny Smith, a historian at Georgia Tech.

“It’s a quieter activism, it’s a safer form of activism,” he adds. “These athletes came of age in a different political climate, and they have been discouraged to be politically active because it has not been economically wise to do so.”

Yet even in the 1960s – seen as a golden age of political activism in sports – Ali and athletes like Bill Russell and Jim Brown were the exceptions. More common were athletes like Willie Mays, whom Jackie Robinson, among others, criticized for lacking political engagement.

“It’s not like if you go back to the ’60s every black athlete was politically active,” says Kevin Blackistone, a visiting professor at the Philip Merrill College of Journalism at the University of Maryland and a sports columnist for The Washington Post.

“You had some black athletes who were active and some who were not,” he adds, “and we have the very same thing today.”

Molded by the times

Outspoken athletes like Ali, Mr. Russell and Mr. Brown were also molded by their environments and the political events of their careers. Carolina Panthers quarterback Cam Newton grew up in Atlanta, but not in Jim Crow-era Atlanta. America is involved in several wars today, but there is no draft for Warriors point guard Stephen Curry to dodge, even if he wanted to.

And while Ali took many of his political views deliberately, he also benefited from circumstance, says Dr. Smith, author of the book “Blood Brothers: The Fatal Friendship Between Muhammad Ali and Malcolm X.”

“When he was drafted, he was thrust into a position where he has to evaluate his political views, his political identities,” Smith adds. “He goes through an evolutionary process, a self-teaching period.”

Throughout his subsequent three-year ban from boxing, when he made many of his college speeches, he further refined his politics.

“When he wasn’t boxing, it forced him to examine his own identity and who he was beyond being a boxer,” Smith says.

Today’s athletes could go through a similar evolution, experts say. Ali could speak out, knowing the civil rights movement would back him. In today’s era of the Black Lives Matter movement – which is taking several cues from the Black Power movement of the 1960s – contemporary athletes could find similar support.

Many already have, says Professor Blackistone. Cleveland Cavaliers star LeBron James tweeted his support of Trayvon Martin after the 17-year-old was shot and killed in Florida. A few years later, a number of NBA teams wore “I Can’t Breathe” T-shirts in reference to Eric Garner, a black man who suffocated while being arrested in New York in 2014. Others are speaking out on issues like marriage or pay equality.

New times, new opportunities?

But in some ways there is room for today’s athletes to be even more political than Ali’s generation, particularly star athletes, some argue. In Ali’s day, professional athletes made just enough money to be comfortable. Many worked other jobs in the off-season. During his ban, Ali spoke at those colleges as much out of economic necessity as political motivation.

The money in contemporary sports “may in some ways insulate them” from the financial retribution Ali suffered for speaking out, Blackistone says. And with social movements like Black Lives Matter gaining momentum and political recognition, more people may want athletes to speak out than they realize.

Pierce, the trainer at The Ring, doesn’t think athletes should be obligated to express their political opinions given their fame and status. But he values those who do all the more. The other three people he would have liked to meet, besides Ali? Bill Russell, Jim Brown, and Bruce Lee.

“What they went through, how they responded. I think that’s what made them great for me,” he says. “That made them appeal more to me than other athletes.”