Parkersburg, Iowa, emerges as model for tornado recovery

Loading...

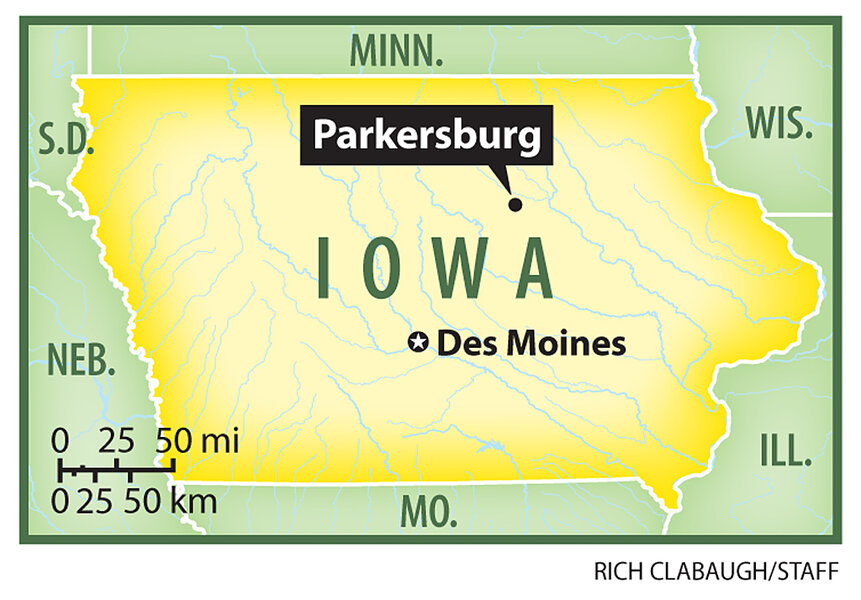

| Parkersburg, Iowa

Even after a devastating tornado, you can rebuild again.

That's the message of hope from Parkersburg, Iowa – a rural bedroom community that was ripped apart three years ago by a monster tornado similar to the one that leveled Joplin, Mo., on May 22.

On May 25, 2008, Parkersburg took a direct hit from a tornado that left a trail of destruction 43 miles long and about a mile wide. Cars were wrapped around trees, most of which were stripped even of their bark. In the town of 2,000, some 288 homes and 22 businesses were ruined, and seven people died.

But today, the path of the giant EF-5 tornado is visible only in the area's lack of mature trees. In the footprint of the tornado have risen new gray and tan homes, some sporting an extra garage and a re-inforced basement.

Only one year after the tornado, the high school, which had been destroyed, displayed the shiny trophies its football team had won, and it opened a new basement-level, cement-enclosed wrestling room, which doubles as a storm refuge for the student body and faculty.

Many communities that have recovered from such disasters do so because they have a unity of purpose and a determination to pick themselves up off the ground. In some cases, the communities have surprised themselves with how fast they recovered. At least one town has used a tornado as an opportunity to reinvent itself.

"You keep moving forward; you remain positive," says Jon Thompson, superintendent of the Aplington-Parkersburg school district, adding that the community's strong sense of faith was also important for getting past moments of doubt.

In Parkersburg, after the initial shock of losing everything, many residents contacted their insurance companies to fund the process of removing the debris and to start replacing their property. Most had to find lodging out of town, but city officials encouraged them to rebuild so local businesses would want to remain. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) stepped forward with checks to help rebuild key public facilities like the high school and City Hall. And thousands of volunteers showed up, ready to help wherever needed.

Recovery from powerful tornadoes is something that many communities in addition to Joplin will be focusing on. For example, Springfield, Mass., and 19 other Bay State communities endured at least two tornadoes on June 1.

This year through May 31, there had been four EF-5 tornadoes, with winds of 200 miles per hour or more. FEMA had declared 13 tornado disasters, compared with a 20-year average of just under 12 for an entire year.

"We know that Joplin is the single most deadly tornado since 1950, when they started keeping records," says Craig Fugate, FEMA administrator. "It's shaping up to be one of the worst years since that time frame."

On June 6, AIR Worldwide, a Boston-based consulting service, estimated the cost to the tornadoes and severe thunderstorms that hit the nation between May 20 and May 27 would result in losses between $4 billion and $7 billion. Tim Doggett, principal scientist at AIR estimated the two major outbreaks of severe weather--the other one taking place in late April-- would likely be the “costliest on record.”

It typically takes five to 10 years for a community to return to some form of normalcy after a major disaster, says Jack Rozdilsky, an expert on how communities rebound from such disasters and an assistant professor at Western Illinois University in Macomb. "What stands out in Parkersburg and what you can take away from them is the extent to which recovery was very rapid," he says. "They found a way to draw on their internal strength for the town's recovery."

A key decision made by the town was to rebuild the high school in a year. This decision was important because the community was proud of its football team.

"In one sense, you are rebuilding the community facility," says Mr. Rozdilsky, who has visited Parkersburg three times. "In another sense, you are building something important that takes the city back to normal."

Parkersburg is not shy about showing itself off. City officials consider the community a sort of template for how small towns ravaged by tornadoes can recover. They call stricken regions offering not just solace, but also advice. Chris Luhring, the police chief at the time of the tornado, does speaking tours on recovery from disasters.

"The No. 1 lesson is that there is this attitude sometimes – and sometimes it's pervasive – that recovery is not possible," says Mr. Luhring, now a town administrator. "That is something we were told by federal officials almost immediately in the aftermath:... 'Recovery is not possible, and if you do recover, you're not going to be the same.' "

To Luhring, this scaling down of expectations was motivation instead. "They didn't know Parkersburg – the farm mentality, you work hard. We're the only place in the country with four active NFL football players," he says.

One essential in Parkersburg's case was that most residents and businesses had insurance that covered a portion of the cost of rebuilding.

In fact, Luhring remembers going with his father, Larry, who lost everything in the tornado, to visit his dad's insurance agent. As they walked out, his father was sobbing. "He said, 'We're done. We're finished,' " recalls Chris. "I said, 'Dad, it will be all right. The fact of the matter is you can't replace people, but things you can replace.' "

Now, Larry Luhring is back in business making monuments, and he produced an elegant black granite memorial bench that sits outside City Hall.

Parkersburg also received aid from FEMA, which paid 90 percent of the town's $6.6 million cleanup bill. However, the agency is now trying to get $1 million back because the school system hired a construction coordinator so it could rebuild the high school quickly. FEMA maintains that the school should recoup the costs associated with the construction coordinator from its insurance company.

"FEMA can be a friend or a frustration," says Mr. Thompson, the superintendent.

It's important, say Thompson and others, to document every decision FEMA makes because the agency sometimes shuffles relief crews in and out, which can result in conflicting decisions. FEMA is trying for smoother handoffs and minimal shuffling, Mr. Fugate says.

One thing that's vital for places like Joplin, Chris Luhring says, is to channel the huge number of volunteers who will show up. "We had our own volunteer coordinator, a 40-hour-a-week job," he recalls. "We organized them to the nth degree."

Parkersburg provided transportation for the volunteers, plus a chart at a coordinating center showing them where to go. "They are there to help you and they want nothing in return," Luhring says.

That's precisely what happened in another place devastated by a tornado. In February 2008, Union University in Jackson, Tenn., lost 75 percent of its campus housing to a monster twister. Damages totaled $40 million to $45 million, says Mark Kahler, associate vice president for university communications.

Before long, college students from other universities came to help with landscaping and cleanup. Local people arrived wearing work gloves and carrying power tools. And children from Greensburg, Kan., which had been destroyed by a giant tornado only a year earlier, sent in pennies they had collected.

"The concept of Tennessee volunteers took on a whole new meaning," Mr. Kahler says.

The university rebuilt the dorms in time for the following school year.

Greensburg itself is instructive in terms of rebuilding. After an EF-5 tornado leveled 96 percent of the community, the town of 1,500 decided not only to rebuild, but to make Greensburg a better place to live.

"Early on, they decided to incorporate the concepts of green or environmentally friendly into their recovery," says Western Illinois University's Rozdilsky, who has studied the town.

For any of these towns, FEMA can take them only so far, Fugate says, especially since jobs and part of a town's tax base may have been destroyed.

"That's why we have to work in partnership with other federal programs" such as the Small Business Administration, he says.

Back in Parkersburg, one challenge that emerged later on was that some people experienced psychological problems. Sadly, one teenage girl took her life, and one year after the tornado, a young man shot and killed the revered football coach.

But the townspeople put a high priority on helping children adjust to all the changes. A key way they did this: building three parks so any child could get on a bike and reach one. "The people became galvanized about that," says Luhring.

As he stops outside one of the parks, he points out an additional touch. "I told the designer, 'I want as many tornado slides [which twist as they go down] as we can get,' " he says. " 'I don't want that word "tornado" to forever be a bad thing. When you put tornado in front of slide, it becomes almost fun.' "