Presidential debate 101: Does Romney want extra $2 trillion for Pentagon?

Loading...

Does Mitt Romney really want to provide the Pentagon trillions more than the nation’s generals and admirals have requested? The Obama campaign insists that’s the case. At Tuesday’s presidential debate, while discussing the GOP nominee’s fiscal plans, President Obama put it this way: “Governor Romney ... also wants to spend $2 trillion on additional military programs, even though the military’s not asking for them."

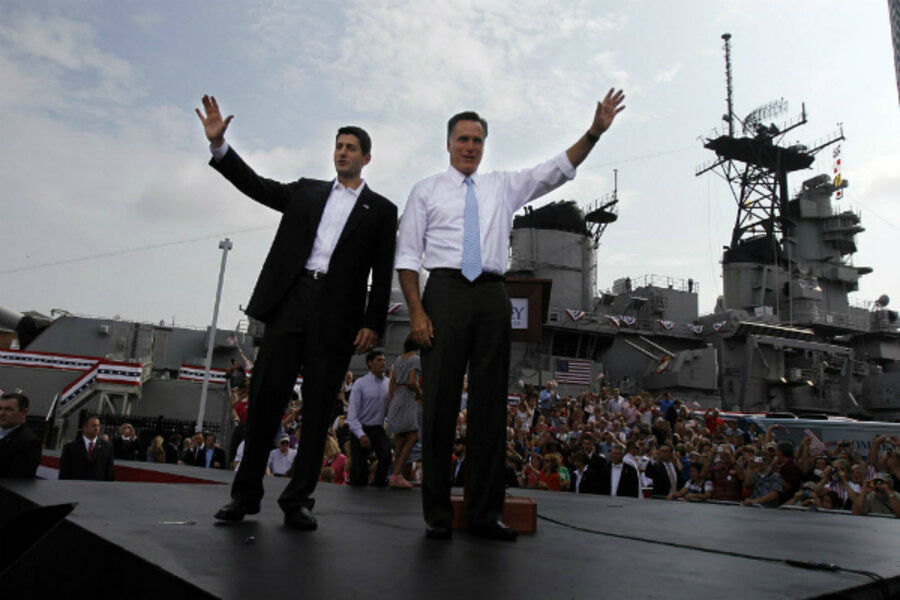

Romney didn’t really engage in discussion on the issue. But his running mate, Rep. Paul Ryan (R) of Wisconsin, did earlier this month in the debate between vice presidential candidates in Kentucky. When Vice President Biden made the $2 trillion assertion, Representative Ryan hit back with his own take: The Obama administration’s plans would actually lead to a reduction in military forces.

“Look, do we believe in peace through strength? You bet we do,” said Ryan.

OK, then. The two sides are lobbing charges back and forth as if they’re engaged in a wonk version of dodge ball. We’ll try to shed some light on this issue as best we can. Remember that big Washington budget numbers are often far squishier than you’d think, given the apparent precision of numerals.

We’ll start with a fact that neither campaign disputes. In a National Security White Paper, the Romney campaign has vowed that it will set a floor for core defense spending at 4 percent of Gross Domestic Product.

By way of comparison, the Obama administration’s 2013 budget proposes a core defense budget – spending which excludes the costs of war operations – of about $525 billion, which should be equivalent to about 3.3 percent of GDP.

So how much would it cost to dial defense spending up to 4 percent of US output? Travis Sharp, an analyst at the Center for a New American Security (a think tank founded by two current Obama administration officials), has looked at the question pretty thoroughly. Using Congressional Budget Office numbers to predict economic growth, and figuring that it would take Romney a few years to get up to the 4 percent number, Sharp puts the 10-year cost of total Romney administration defense spending at about $7.8 trillion dollars.

The Obama administration in contrast is looking at 10-year defense numbers that are essentially flat, plus increases for inflation. Total these numbers up, and you get $5.7 trillion.

Subtract the predicted Obama numbers from the possible Romney totals and you get ... drum roll ... $2.1 trillion! That’s where the “$2 trillion” part of Obama’s debate night assertion came from.

It’s true that predicting military budgets this far in advance is a little bit like predicting your budget for electronic devices in 2017. You don’t know what kind of new phones, DVRs, tablet computers, and so forth will even exist by then, or what you’ll want to use them to do. Neither does the Pentagon know what the context of the America’s security situation will look like a decade hence or what mix of weapons will best meet the nation’s needs.

Plus, a defense budget of 4 percent of GDP would be far from unprecedented. In some ways it would be a return to a typical number. From 1949 through 1994 the DoD budget reached at least the 4 percent of GDP level, and often higher. As American Enterprise Institute defense analyst Tom Donnelly notes in his take on this subject in the Weekly Standard, during the 50 years of the Cold War the average for defense spending was 6.3 percent of GDP.

We’ll also note that a 10-year budget prediction beginning in 2013 carries to 2022, two years beyond Romney’s term in office, if he wins this fall and again in 2016.

Still, the Obama administration didn’t just pull its $2 trillion figure out of Joe Biden’s Amtrak commuter bag. There’s at least some math behind that assertion.

So let’s move on. What about the second part of Obama’s charge – that Romney wants to spend this money on new stuff that the military isn’t even asking for?

Well, maybe they’re not requesting it because the Obama administration gets to tell them what to ask for in the first place. Last time we looked, there was a civilian Obama appointee running the Pentagon – Secretary of Defense Leon Panetta. He works with the White House’s Office of Management and Budget to set defense budget request levels. It’s true the military gets to lay out what they think they need for national security, but the budgeting process is top down as much as bottom up. Obama might just as well have said, “Romney wants to add money that I don’t.”

We'll end with an aside: The Pentagon in its history has at times played artful budget games. It’s not unknown for DoD budgeteers who are trying to get under top line numbers to slice out programs they know are popular with Congress. That way they can keep their civilian bosses happy while remaining assured that lawmakers will put the programs back in to keep assembly lines in their district or state humming along.