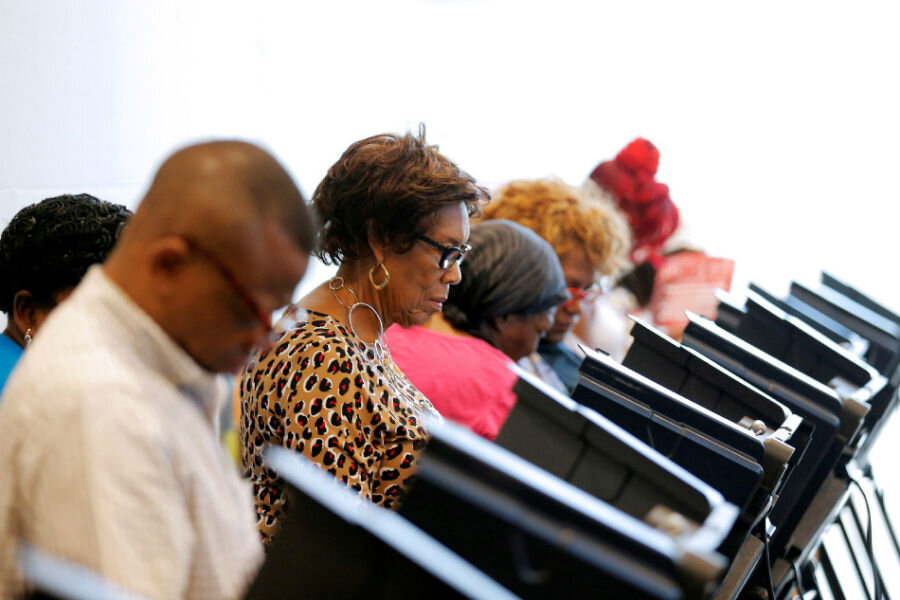

North Carolina voter purge: Should citizens investigate the rolls?

Loading...

A federal judge in North Carolina ordered state election officials on Friday to restore thousands of voter registrations that were purged from the rolls in recent months, with some alleging that the cancellations targeted African-Americans voters.

On Monday, some affected voters – who had showed up at the polls only to find themselves removed – filed a lawsuit together with the NAACP calling the cancellations an illegal effort to suppress African-American votes.

“[T]here is little question that the County Boards’ process of allowing third parties to challenge hundreds and, in Cumberland County, thousands of voters within 90 days before the 2016 General Election constitutes the type of ‘systematic’ removal prohibited by the [National Voter Registration Act],” US District Judge Loretta Biggs wrote in her ruling, as reported by News & Observer.

Judge Biggs had earlier called the purge “insane,” similar to something out of the Jim Crow era.

While the incident occurs in the midst of an election season rife with talk of voter fraud, citizen efforts to "clean" voter rolls has gone on since at least 2012.

Some studies have pointed out that voter registration systems indeed need upgrades to filter out ineligible individuals. But are citizen-led efforts the best method to address it – and is Biggs clamping down on a grassroots movement to improve the electoral system?

Some experts say that relying on citizen efforts without in-depth validation by state and federal officials can be dangerous.

“There is a process in the National Voting Rights Act [NVRA] for addressing duplication and other problems with voter lists, and that process is pretty clearly stated,” says Thad Hall, subject matter specialist with research company Fors Marsh Group and a former professor at the University of Utah, in a phone interview with The Christian Science Monitor.

“The problem with citizens trying to do it is that we already know from voter registration that there are a lot of little things that occur that makes you think something is wrong with the list when there isn’t.”

Mr. Hall raised examples of similar names, errors in data entry for birthdays, outdated addresses, and other issues. He points out that after identifying suspicious cases, the key is the research and investigation to determine if the case is valid.

In the North Carolina case, members of the Voter Integrity Project had sent mail to addresses in the three counties and marked down those that came back as undeliverable or unreturned. They submitted those names to county boards, who then canceled their voter registration.

But according to federal law, states cannot remove voters from the roll within 90 days of the election and two federal elections have to pass before it can take effect. Judge Biggs also raised concerns about the strategy of relying on unreturned mail to determine that the voter doesn’t live in a registered location. They may have moved within the county and remain eligible to vote there, or, as in one of the plaintiff’s cases, noted by CNN, gets her mail from from the post office box and not her house.

The North Carolina State Board of Elections countered that private individuals can challenge eligibility of any county voter up to 25 days before the election. Before the registration is revoked, the affected individual will be able to receive a notice and attend a hearing with the board of elections as well. But since they sent the mail to the same addresses, many of the voters may not be aware that they're being challenged.

“The biggest danger is removing someone from the roll who shouldn’t be removed,” explains Charles Stewart III, professor of political science at MIT.

“We see increasing attempts by citizen groups and local officials in the heat of a campaign trying to challenge voters," he tells the Monitor. "It’s improper in the days before election, unless there is direct evidence.”

Professor Stewart described multi-state efforts to update voter rolls, such as the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC) that compares multiple databases across states to reflect changes and alert officials to out-of-date data in the system.

As of July, 20 states and the District of Columbia have signed up for the program. Other solutions tested by various states include automatic voter registrations and same-day voter registrations.

But some experts say that scant evidence exists of voter fraud occurring even with outdated voter registration systems, and the citizen groups involved in these incidents have been revealed in investigations to have partisan ties, thus igniting suspicions.

“It’s troubling when private groups are doing this because they may be wrong and because they may be engaging in partisan manipulation,” Daniel Tokaji, law professor at Ohio State University tells the Monitor in a phone interview. “I think the big problem is that some states fail to comply with the requirements of the NVRA. It’s not as though we have an epidemic of voting fraud.”

The North Carolina State Board of Elections has said it is working to establish procedures necessary to comply with the court orders before election day.