Why Americans are so angry

Loading...

Heather Gass always felt she had to suppress her conservative views, living as she did in the liberal San Francisco Bay area. A year ago that all changed.

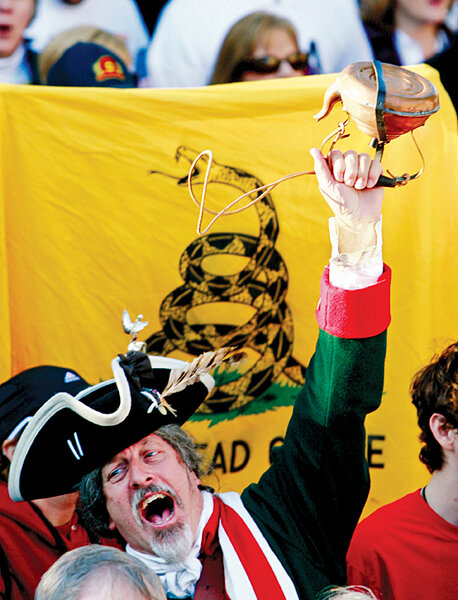

CNBC financial reporter Rick Santelli had just blasted the Obama administration's plan to help homeowners facing foreclosure, and called for a "tea party" protest in Chicago. The idea caught fire around the country, and soon Ms. Gass, a 40-something real estate agent, was organizing weekly street-corner demonstrations in her hometown of Orinda, Calif.

Her focus was fiscal discipline, aimed not just at the $75 billion mortgage bailout but also the administration's $787 billion stimulus package and President Obama's budget. She remembers her first signs well: "Stop printing money" and "China owns us." By Congress's summer recess, when opposition to Mr. Obama's healthcare plan burst forth, she had 100 people protesting on street corners, she says.

Fast-forward to February 2010. Gass is still out there every Friday, her 6-year-old son in tow. Political operatives are calling her up for advice. Her roster of influential tea party activists – "Heather's list," as local politicos call it – is creating buzz. "We're not dangerous," says Gass. "We're your neighbors. But we've been underground. We're not underground anymore."

Gass says she's beyond anger over the direction of the country and is in "action mode." Whatever it's called, that intensity of feeling – the passion that led her to travel last month to the Tea Party Convention in Nashville and that drives her to tears when she worries out loud about the America her son's generation will inherit – is unmistakable.

Heather Gasses exist all around the country, ordinary American conservatives who are fed up and leading the charge. There's frustration on the left, too – aimed not only at the Republican Party, for hindering Obama's agenda, but also at Wall Street and its "no-limits-casino banking culture," as liberal blogger Arianna Huffington writes on her Huffington Post website.

She and other leaders on the populist left, such as the Rev. Jim Wallis, are urging people to move their money from "too big to fail" banks into community banks.

There's also disaffection among moderates, frustrated by the high degree of political polarization that leaves little room for compromise on major policy matters. But efforts in the last decade to build a "radical middle" movement – a drive to marry the best ideas of the right and left – seem to have faded.

The stunning decision by Sen. Evan Bayh (D) of Indiana, one of the Senate's few moderates, not to run for reelection cast the hollowing-out of the middle in sharp relief.

On the extreme edge, some people have even been moved to violence – like Joseph Stack, who flew his plane into an IRS office in Austin, Texas, on Feb. 18.

So what does this all add up to? Are we "mad as hell," like TV anchor Howard Beale ranting to viewers in the 1976 Hollywood classic "Network"? Is today's real-life incarnation, Glenn Beck of Fox News, whipping us into a frenzy of revolt against Washington?

Not necessarily. Pollster Scott Rasmussen reports that 75 percent of Americans are "angry," but his question is framed solely around anger: "How angry are you at the current policies of the federal government?" Forty-five percent replied "very angry" and 30 percent said "somewhat angry."

But when Americans are given a choice of "angry," "dissatisfied," "satisfied," or "enthusiastic" about the way the federal government works, "dissatisfied" is the most popular choice at 48 percent, according to an ABC News/Washington Post poll. An additional 19 percent chose "angry."

This net negative of 67 percent doesn't come close to the same poll's finding in October 1992, during the last time of political turmoil over fiscal policy. Then, 25 percent of Americans were angry, and 56 percent were dissatisfied, per ABC. A month later, third-party presidential candidate Ross Perot won 19 percent of the vote and cost President George H.W. Bush a second term.

In 1992, unemployment had peaked at 7.8 percent – well below today's level – and yet voters then were angrier than they are today. So it's not just about unemployment. "Consider also the duration of the downturn, the tenure of the administration, the level of effort, the sense of empathy, and other atmospherics," says Gary Langer, director of polling for ABC News.

Obama emerged from his post-inaugural honeymoon long ago, but he's still only 13 months in office. If the public remains unhappy with the economy and with his administration's recovery efforts, anger could rise. As things stand today, the Democrats already could lose well more than 24 House seats this November, the post-World War II average loss for the president's party in midterm elections.

For now, the angriest bloc of voters is conservatives, at 32 percent, according to ABC. Ten percent of liberals and 12 percent of moderates are angry. Higher levels of anger and declines in job approval for Obama could point to greater-than-average losses in November, potentially even the loss of Democratic control on Capitol Hill. Nonpartisan political handicapper Charlie Cook already predicts the Democrats will lose the House.

But eight months before the midterms, Obama and the Democrats still have time to regroup. During President Reagan's first two years in office, the recession was deep and persistent – with unemployment matching today's levels – and yet the Republicans lost only 26 seats in the 1982 midterms, just above average. Perhaps Reagan's sunny persona helped. And having taken office on a wave of anti-incumbent feeling, defeating President Carter in the process, Reagan managed to maintain an outsider's aura long into his tenure, which may also have helped stave off worse losses in the first midterm.

Obama, too, has a loyal base of support that has largely stuck by him during his tough first year, even as less-committed independent voters have peeled away. But if anger continues to rise across the board, the outcome in voting booths could be far worse for Democrats.

Every disaffected voter has his or her own story. Gass calls her new activism an "awakening," an acknowledgment of a nagging feeling she always knew was there, but was too busy to act upon. Now she feels she has no choice. "We have borrowed and spent our way into the biggest black hole," she says, "and we are heading into the abyss."

Obama supporters who speak in less-than-glowing terms about the status quo can be described more as disaffected than angry.

"I think the biggest disappointment is that politicians on both sides are looking out for their best interests instead of where the country needs to be," says J.P. Arena, a social worker in Massachusetts, who describes himself as a left-leaning Independent.

"Whether it's Obama, whether it's Republicans, people aren't putting the needs of the country first." Mr. Arena says Obama still has his support "for now, but it's a tentative support."

Then there are the Obama supporters who are giving up altogether – and leaving the country. Susan and Fred Klopfer, lifelong Democrats from Mount Pleasant, Iowa, are moving to Mexico in September. Mr. Klopfer, a psychiatrist with the state Department of Human Services, accepted early retirement after learning that his facility was closing in June.

Mrs. Klopfer says once he retires, they won't be able to afford the $1,800 per month she estimates their healthcare will cost – if they could get coverage at all, given preexisting conditions. She doesn't completely understand Obama's healthcare proposals, but it doesn't matter now. They're leaving.

"My husband and I lost 40 percent of our retirement savings, and we'll never see it again," she says. "If we had a Congress that was doing its job and safeguarding and protecting the investment environment, we could have used the retirement we had saved....

"I never thought we'd have to leave our country to retire."

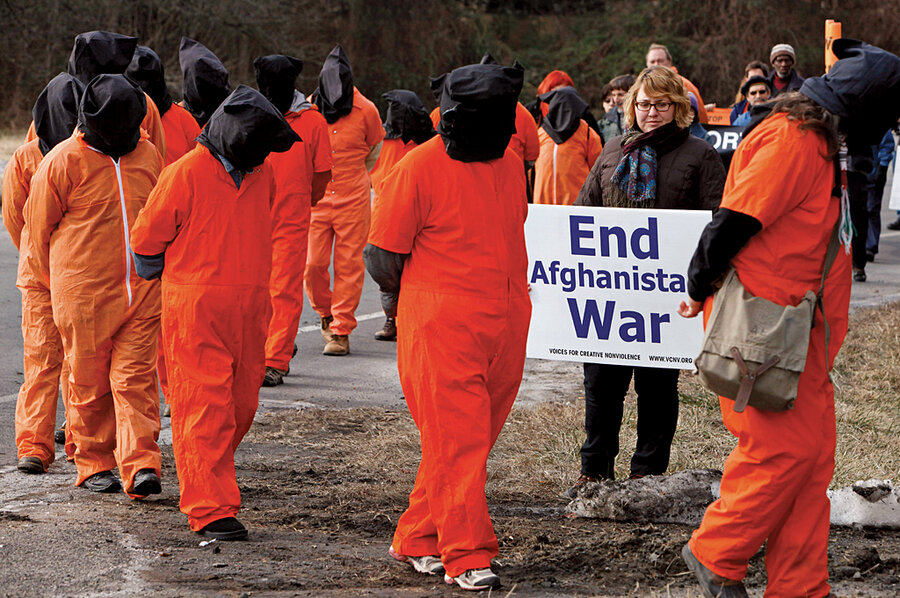

Waves of public discontent are older than the republic. The original tea party, after all, kicked off the American Revolution. Typically, populism has been a left-wing phenomenon; it erupted in the 1880s as a movement led by farmers unhappy about grain prices and the gold standard. The People's Party formed in the 1890s, but was eventually absorbed into the two-party system – the common fate of third-party movements in America.

It's not just economic conditions that lead to populist revolts. "A sense that people in power – the political elite, governing classes – are not responding to the most obvious problems that Americans face" is another factor, says Michael Kazin, a historian at Georgetown University.

Bankers are also common villains, going back to President Jackson's clashes with the Second Bank of the United States in the 1830s. Today, it's the large bonuses paid to the executives of bailed-out financial institutions that elicit the most anger from Americans – 62 percent, according to a recent Pew Research Center poll. The bailouts themselves angered 48 percent of Americans, partisan gridlock angered 39 percent, and the budget deficit angered 37 percent.

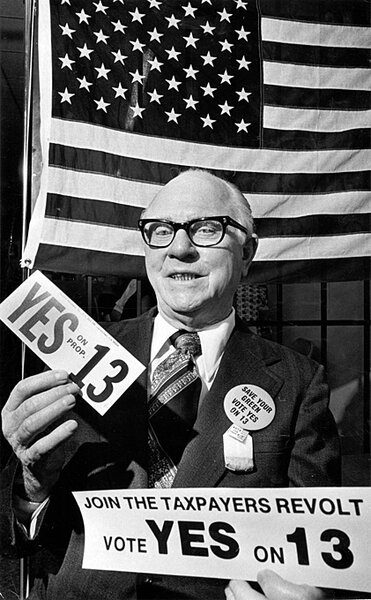

In its most recent iterations, populism has risen from the right. According to historian Bruce Schulman of Boston University, the antitax revolt of the late 1970s and early '80s represents the immediate progenitor of the tea party movement.

More than half the states passed some kind of tax limitation or spending- cut initiative during that period – most famously, Proposition 13 in California and Proposition 2-1/2 in Massachusetts. Like the tea party movement, the tax revolt remained a state-centered phenomenon and resisted becoming a national political party or a personality-dominated movement.

Reagan made the tax revolt work for him politically by getting out in front of it, endorsing, for example, the Kemp-Roth tax-cut plan of 1981. Even after his reelection, when some conservatives complained that he was spending too much, expanding government too much, and accommodating the Soviets too much, their argument never got much traction.

"Reagan was their guy," says Mr. Schulman. "He was the best they were going to have, and they knew it."

President Clinton was able to discipline his liberal constituents – opponents of welfare reform and deficit reduction – in much the same way and carve a centrist path that ended up earning him two terms in office.

Obama has tried to get in front of today's conservative populist sentiment by proposing a freeze on domestic nonentitlement spending. He has also tried to appease the populist left by announcing a $100 billion fee on large banks, a jobs program, and a plan to prevent financial institutions from engaging in risky trading. But until unemployment shows clear signs of abating, Obama is going to be burdened politically.

Some analysts raise the Ross Perot movement of the early 1990s as a more recent precursor to the tea partyers, with a common focus on reining in government spending and deficits. Larry Sabato of the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, suggests that if the tea partyers are smart, they'll learn from the implosions that killed off the Perot movement.

"The only thing holding this very diverse cast of Tea characters together is an emphasis on the fiscal – spending, taxes, and debt," Mr. Sabato writes in Politico. "As with Perot, these concerns resonate with a substantial portion of the population, especially Independents. The Tea Party needs to borrow (or buy at a discount) some of Perot's color-coded pie charts, and keep its followers focused there."

The tea party phenomenon, unlike the personality-driven Perot movement, remains diffuse, and leaders insist that it can succeed only by maintaining local autonomy. Last month in South Carolina, local tea party groups merged with the state Republican Party – aimed at sharing resources and coordinating messaging – but within days, the union was fraying.

In Nevada, a group calling itself the Tea Party has qualified to appear on the 2010 ballot and is reportedly planning to put up its own Senate candidate. This move could end up helping Nevada Sen. Harry Reid (D), who has been trailing in his reelection bid, by siphoning votes away from the Republican nominee. It's a scenario reminiscent of last November's special election for a New York House seat, in which nationwide tea party support for the third-party Conservative candidate ended up handing the election to the Democrat.

More interesting, in a way, is how the tea party movement is unique. Georgetown's Mr. Kazin is struck by how "it's gotten so apocalyptic in the hands of some people, like Glenn Beck."

"Whenever there's a lot of fear in the country, there are people willing to ratchet it up," he says.

On the right, that fear crystallized soon after Obama took office, but it was building under President George W. Bush, whom many conservatives see as having strayed far from their core principles. "Then Obama comes in, and he seems like he's going to try to revive liberalism, which to a lot of people on the right means socialism," says Kazin. "So where do you turn? You can't turn to anybody in the political elite, so you have to do it yourself."

The round-the-clock media environment of cable TV, talk radio, and the Web, enhanced by the latest social networking tools, has allowed the tea party movement to ramp up rapidly like none other before it.

The biggest challenge for the movement may be solidifying a positive image in the public eye. The recent ABC News/Washington Post poll shows 35 percent of Americans view the tea party favorably, while 40 percent see it negatively. Nearly two-thirds say they don't have a strong sense of what the movement is about. So when news reports of tea party events focus on fringe concerns, such as immigration and Obama's heritage, the movement's appeal could narrow.

Even if the tea partyers can claim some headway in building public support, their progress is not seamless. On the heels of Republican Scott Brown's improbable Senate victory in Massachusetts, Oregon voted in a statewide referendum to uphold tax increases on wealthy individuals and businesses in support of public education and social services. And in his first important vote, Senator Brown sided with the Democrats.

In the end, the tea party movement may have the effect of pulling the GOP to the right. An important part of its birth, after all, is a reaction not just to the Democratic Obama but also to his Republican predecessor, who initiated the spending and bailouts that Obama has continued. The American political system is rigidly binary, Republican versus Democrat, and most third-party adherents inevitably are absorbed by one or the other.

As for public anger, there are signs that Americans see cause for hope. A January Pew poll finds that while the national mood remains "grim" – only 27 percent of Americans are satisfied with the way things are going – there is "considerable optimism" that 2010 will be a better year than 2009.

"Sixty-seven percent say the coming year will be better, compared with 52 percent who said that last January and 50 percent in December 2007," Pew reports.

The poll found partisan differences in optimism, with 83 percent of Democrats saying 2010 will be better than 2009, compared with 60 percent of Independents and 55 percent of Republicans. But those numbers represent an increase for all three groups.

Maybe it's the can-do American spirit, or even that sense of American exceptionalism that runs through the national narrative. Or, quips a public- opinion analyst, "maybe people think it can't get any worse."

• Patrik Jonsson in Nashville, Tenn., Tracey D. Samuelson in Boston, and Carmen K. Sisson in Slidell, La., contributed to this report.