Van Gogh painting: Why Yale can keep $120 million painting

Loading...

| New Haven, Conn.

A federal judge in Connecticut has dismissed the claims of a man who said he was the rightful owner of a Van Gogh painting that's been on display at Yale University for about 50 years.

Judge Alvin Thompson on Thursday granted Yale's request to deny the claims to the painting by Pierre Konowaloff, who says "The Night Cafe" was stolen from his family during the Russian revolution.

Yale sued in 2009 to assert its ownership rights and to block Konowaloff from claiming it. Konowaloff sought the return of the painting, or damages, and valued the painting at $120 million to $150 million.

The judge agreed with Yale's argument citing the act of state doctrine in which U.S. courts don't examine the validity of foreign governments' expropriation orders. He called the piece one of the world's most renowned paintings.

"We're pleased that the court has dismissed Konowaloff's claims," said Jonathan Freiman, Yale's attorney. "The Night Cafe is a timeless masterpiece that the public can see free of charge, and in this suit Yale has worked to make sure it stays that way."

Konowaloff says his great-grandfather, industrialist and aristocrat Ivan Morozov, bought "The Night Cafe" in 1908. Russia nationalized Morozov's property during the Communist revolution, and the Soviet government later sold the painting.

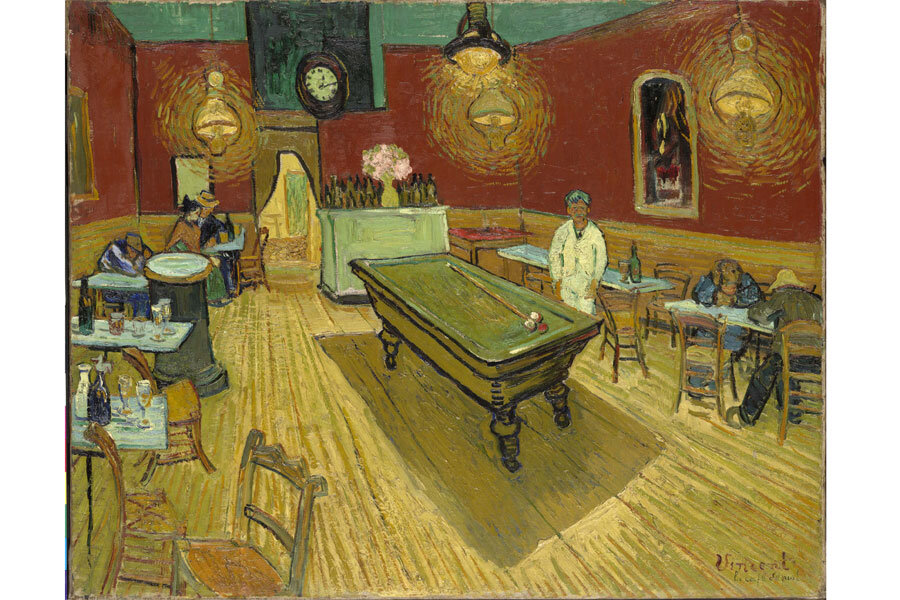

The 1888 artwork, which shows the inside of a nearly empty cafe with a few customers seated at tables along the walls, has been hanging in the Yale University Art Gallery.

Yale argued that the ownership of tens of billions of dollars' worth of art and other goods could be thrown into doubt if Konowaloff were allowed to take the painting. Any federal court invalidation of Russian nationalization decrees from the early 20th century also would create tensions between the United States and Russia, Yale has said.

The university says former owners have challenged titles to other property seized from them in Russia, but their claims were rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court and state, federal and foreign courts.

Konowaloff's attorney, Allan Gerson has said neither Russia nor the United States expressed any concerns about the case and that any ruling would not affect Russian paintings.

Gerson says the trend by U.S. courts has been to invalidate confiscations of art. He has said in court papers that Yale's argument amounted to compelling U.S. courts to "rubber-stamp good title on any dictator's plunder."

Gerson said Friday he was seriously considering an appeal of the ruling. He said he was shocked the judge refused to provide an oral hearing, especially after his side submitted evidence from the Russian Federation archives.

"There's never been another case in which act of state has been invoked where the state — here, Russia — that the court is ostensibly trying to protect from embarrassment has actually cooperated with the court," Gerson said.

The judge said that evidence was not relevant for the ruling because it involved an investigation of the sale of the painting in 1933 rather than the 1918 appropriation by the Soviet government.

Yale received the painting through a bequest from Yale alumnus Stephen Carlton Clark. The school says Clark bought the painting from a gallery in New York City in 1933 or 1934.

Konowaloff has called Yale's acquisition "art laundering." He argued that Russian authorities unlawfully confiscated the painting and that the United States deemed the theft a violation of international law.

Yale says the Russian nationalization of property, while sharply at odds with American values, did not violate international law.

Copyright 2014 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed.