Mistrial declared in Etan Patz murder case

Loading...

| New York

The murder trial of a man accused in the 1979 disappearance of first-grader Etan Patz ended Friday with the jury hopelessly deadlocked after 18 days of deliberations, leaving one of the nation's most wrenching missing-children cases still unresolved after nearly two generations.

Jurors said for a third time that they were hopelessly deadlocked in the case against Pedro Hernandez, and the judge declared a mistrial. The Maple Shade, New Jersey, man was a teenage stock boy at a Manhattan convenience store when 6-year-old Etan vanished May 25, 1979. He would become one of the first missing children ever pictured on milk cartons.

Prosecutors have asked to set a new trial date in the case, which frustrated authorities for decades before a tip led them to Hernandez — never before a suspect — and he confessed in 2012. His lawyers said the confession was false, a concoction spun by mental illness, and they said another longtime suspect was the more likely killer.

The mistrial left Etan's parents, who became national advocates for the cause of missing children, to await another trial.

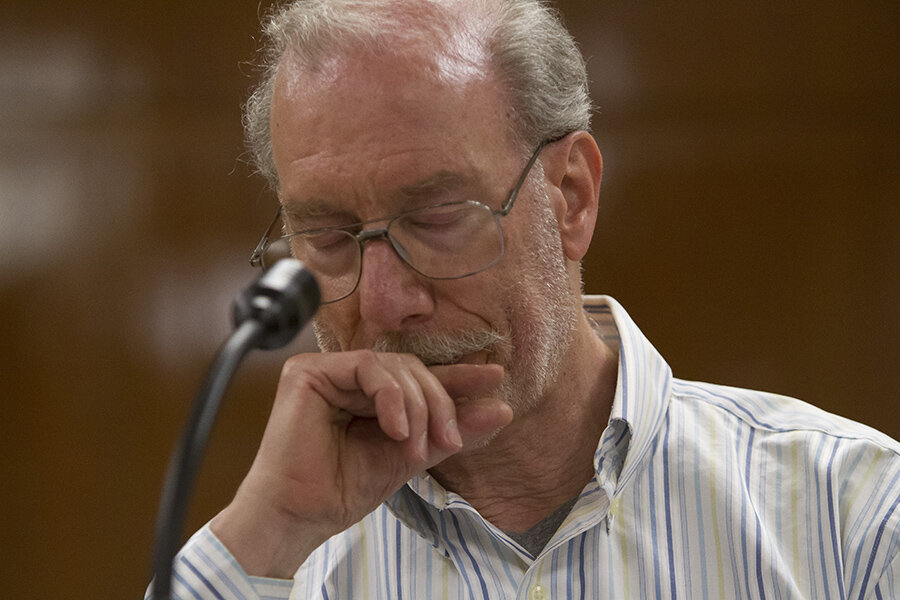

"We are frustrated and very disappointed. The jury has been unable to make a decision. The long ordeal is not over," said his father, Stanley Patz. But, he added, "I think we have closure already."

He tried for years to bring the earlier suspect to account for Etan's death, but after the trial, he said, "I am so convinced Pedro Hernandez kidnapped and killed my son. ... His story is simple, and it makes sense."

Hernandez will remain in jail to await another trial; the first took over three months, including 18 days of deliberations. Jurors announced they were deadlocked twice before Friday, on April 29 and on Tuesday. Both times, the judge told them to keep trying to reach a verdict.

Manhattan District Attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr. said in a statement he believed there was "clear and corroborated evidence" of Hernandez's guilt.

"The challenges in this case were exacerbated by the passage of time, but they should not, and did not, deter us," Vance said in a statement.

After Etan's disappearance, his parents helped shepherd in an era of law enforcement advances that make it easier to track missing children and communicate between agencies. They were at the White House when Ronald Reagan named May 25 National Missing Children's Day.

While New York City detectives frantically searched for the sandy-haired boy, Hernandez moved back to New Jersey and slipped off the radar. His name appears in police files only once before 2012, when he confessed to choking the boy in the basement of the shop, then putting the body in a bag, putting the bag in a banana box and walking it about two blocks away where he dumped it.

But Etan's body was never found. Nor was any trace of clothing or his belongings.

Several members of a prayer circle, an ex-wife and a friend testified that Hernandez had told them at different points during the past three decades that he'd harmed a boy in New York. The jury watched hours of his confession and heard from Julie Patz, Etan's mother, who recounted in clear, sad detail the last time she saw her son.

"Etan is larger than his very little important life," Assistant District Attorney Joan Illuzzi-Orbon said during closing arguments. "He represents a moment in this city where there was a loss of innocence."

But no physical evidence tied Hernandez to the crime; the corner store closed in the early 1980s. No DNA was found. Hernandez's ex-wife testified that she once saw part of Etan's missing-child poster in a box belonging to Hernandez, but authorities turned up nothing.

"As I told you in the very beginning, Pedro Hernandez is the only witness against himself," defense attorney Harvey Fishbein said during closing arguments. "The stories he told over the years, including in 2012, and since, are the only evidence. Yet he is inconsistent and unreliable."

"Pedro Hernandez is not a child killer," Fishbein said.

Fishbein argued the admission was false — the fictional raving of a mentally ill man — and pointed to longtime suspect Jose Ramos, a convicted pedophile who admitted to a federal prosecutor that he had been with Etan the day the boy vanished, according to testimony. Ramos, now jailed in Pennsylvania, has denied killing Etan.

A former jailhouse informant who was working with them gave a stomach-turning account of conversations he had with Ramos that included details on molesting Etan. Manhattan prosecutors never felt there was enough evidence to charge him with the crime.

Hernandez's attorneys had sought to question Ramos on the witness stand but he said he would invoke his right against self-incrimination. He has refused to comment about this case, and says he didn't have anything to do with Etan's disappearance.

Police were brought to Hernandez's door after his brother-in-law called in a tip. He'd seen news reports of an FBI excavation in the SoHo neighborhood linked to the case, after it had been dormant for years. He testified he had long suspected his brother-in-law had been involved in the death of the child.