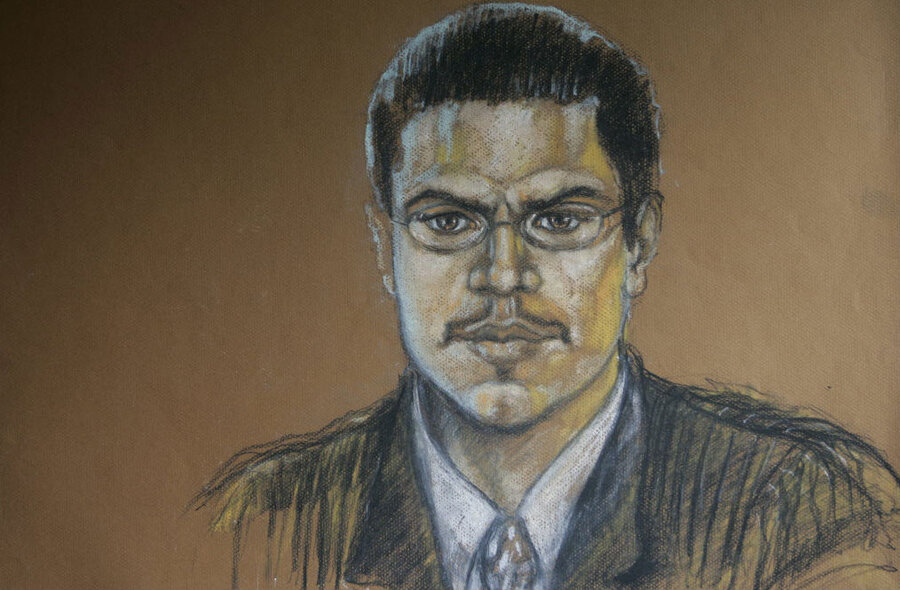

The strange saga of Jose Padilla: Judge adds four years

Loading...

| Miami

Convicted Al Qaeda supporter Jose Padilla received a new prison sentence on Tuesday, adding four years to his existing 17-year sentence in response to a federal appeals court ruling that his initial sentence was too lenient.

Mr. Padilla was convicted in 2007 of involvement in a terror conspiracy and has been serving his sentence in a solitary confinement cell at the US government’s supermax prison in Florence, Colo.

His case has attracted international attention because prior to entering the criminal justice system, Padilla was designated an enemy combatant and held incommunicado without charge at a naval prison in Charleston, S.C.

During his three years and eight months in military detention, Padilla was subjected to harsh interrogation techniques and prolonged isolation that mental health experts said may have caused permanent psychological injury.

Padilla’s mother and brother both expressed concern during Tuesday’s hearing that he may never recover.

“His mind is not there. Jose’s mind is gone,” Estela Lebron, Padilla’s mother, told US District Judge Marcia Cooke. “I don’t know if it is going to come back.”

In a tearful statement to the court, Padilla’s brother, Tomas Texidor, said the military detention and interrogation, and his continued incarceration in a solitary confinement cell in federal prison, was taking a heavy toll on Padilla’s mental health.

“I pray that when he gets out [of prison] he will be able to function again ... use his mind,” he said.

Mr. Texidor added: “I can’t believe this is happening in this country.”

During the hearing, Padilla sat passively at the defense table, his eyes aimed straight ahead, blinking excessively. He wore a tan prison-issue shirt and slip-on shoes (without laces). Throughout the hearing, he was restrained in leg irons and wrist cuffs attached to a belly chain.

The hearing was necessary because after Padilla’s initial sentencing in January 2008, federal prosecutors objected to Padilla’s 17-year prison term. They had asked the judge to sentence him to life in prison.

The Atlanta-based 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled 2 to 1 in September 2011 that Padilla’s sentence did not adequately reflect his criminal history and that the judge was wrong to reduce his sentence to compensate for the years he was held by the military for interrogation.

In preparation for the resentencing, Federal Public Defender Michael Caruso subpoenaed Defense Department officials to obtain documents related to Padilla’s treatment while in military custody. Judge Cooke approved the subpoena requiring the government to release the information.

After providing the records to Mr. Caruso, prosecutors agreed not to seek a sentence for Padilla greater than 30 years. In exchange, Caruso agreed not to use any of the discovered material in the sentencing hearing.

That agreement meant that Cooke was likely to sentence Padilla within a range of 21 to 30 years under federal sentencing guidelines.

It was clear from the judge’s comments and demeanor during the hearing that she felt her original 17-year sentence was fully justified. But it was also clear that she felt constrained in her options.

In setting the new sentence at 21 years, Cooke said she was concerned about the problem of US citizens being recruited and used in conflicts abroad.

Her comment came as the US government is scrambling to identify Americans who may be returning from the Middle East to target the United States after fighting with the Islamic State, a militant group, in Syria and Iraq.

The judge noted that in Padilla’s case, he had been recruited in the US by two individuals, both of whom received shorter prison terms than him.

Caruso argued that the two other co-defendants were significantly more culpable than Padilla, who in the late 1990s was newly converted to Islam with a seventh-grade education and no sophisticated understanding of international politics.

Prosecutors disagreed. “What makes Padilla more culpable is that he was willing to get the training to kill innocent civilians,” Assistant US Attorney Ricardo Del Toro told the judge.

Padilla and the two other men were convicted in 2007 following a five-month trial in federal court. Prosecutors said the three were part of a North American support cell that provided money, equipment, and recruits to Al Qaeda and other radical Islamic groups overseas.

Prosecutors alleged that Padilla attended an Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan after joining a conspiracy in the US to “murder, kidnap, and maim” persons overseas.

Padilla was also charged with conspiring to provide material support and actually providing material support to a terrorist organization, knowing that the support would be used in a terrorist plot to murder, kidnap, and maim individuals overseas.

The jury convicted Padilla of all three charges.

The essence of the government’s case against Padilla was that he attended an Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan and that the act of accepting that training demonstrated Padilla’s intent to engage in terrorist acts.

Caruso said the camp in Afghanistan provided basic military training. But he added: “There is no evidence that Jose received terrorist training.”

The public defender said that young, naive Muslims are recruited from the US and elsewhere with a sales pitch that they will be fighting to defend helpless Muslim women and civilians from atrocities, such as those that Russian forces committed in Chechnya. They are told it is a religious duty to provide such a defense.

Padilla’s name first appeared in the news in 2002 when US officials accused him of plotting a dirty-bomb attack on a US city. After officials made that claim, then-President George W. Bush declared Padilla an enemy combatant and ordered him held for interrogation at the naval brig in Charleston.

The move was controversial. As a US citizen arrested on American soil, Padilla was supposedly entitled to the protections of the US Constitution. The administration disagreed.

Various aspects of the case have been litigated at all levels of the federal court system. When Padilla’s case finally reached the US Supreme Court, the government moved Padilla to the criminal justice system and put him on trial in Miami.

The action mooted the pending Supreme Court case and shielded the government from judicial oversight of Padilla’s treatment in military detention.

Despite the widely publicized charges used to justify Padilla’s military detention, the US government has never produced evidence of an actual dirty-bomb plot.

Government officials made 88 recordings of Padilla’s interrogations. But, according to court documents, the DVD recording of Padilla’s final interrogation was somehow “lost.”

In her comments to the judge, Padilla’s mother said he is not an evil person and that he is not a terrorist.

“Before they destroyed those tapes, he told me what they did to him,” Ms. Lebron said. “They tortured him.”

At one point in the hearing, Cooke expressed concern that critics might view a sentence on the low end of the guidelines as “a pass” for Padilla.

Caruso disagreed. He said his client would be serving 21 years in a solitary confinement cell. “I don’t consider that a pass,” he said.

Padilla, the public defender added, has already been largely destroyed. “I have seen the slow, slow destruction of this man since he’s been in civilian court,” Caruso said.

In his argument, Caruso mentioned the case of Ali Saleh al-Marri, who was also designated an enemy combatant and held for interrogation at the Charleston brig.

Unlike Padilla, there is direct evidence that Mr. Marri was involved with Al Qaeda leaders, including Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, the alleged mastermind of the 9/11 attacks.

At Mr. Mohammed’s direction, Marri came to the US and set to work identifying potential terror targets. There is also evidence that Marri was in contact with Mustafa al-Hawsawi, an alleged moneyman in the 9/11 attacks.

Marri was held for six years in military detention and interrogated. At one point during the harshest treatment, he smeared the inside walls of his cell with his own excrement.

Unlike Padilla, Marri eventually entered a plea agreement with the US government and was promised no more than a 15-year sentence. The judge, taking into consideration Marri’s treatment in the brig, cut the sentence to eight years.

The government did not appeal that reduction. As a result, Marri is expected to walk out of prison on Jan. 18, 2015 – in four months.