Documents offer rare inside look at Chicago priest sex abuse

Loading...

| Chicago

Some 6,000 documents from the Archdiocese of Chicago posted online Tuesday offer an unprecedented look into the internal discussions and actions of a major branch of the Roman Catholic Church as it dealt with past clerical sexual abuse of minors.

The documents include letters from parishioners questioning the behavior of certain priests, statements by victims, internal memos related to accusations, and a 2008 deposition from current Chicago Cardinal Frances George. Many of documents suggest that, as recently as 1997, many accused priests were removed from their parishes and given monitoring restrictions but were not handed directly to local law enforcement.

The archdiocese says it is trying to heal the mistakes of the past, and that the documents, released as part of a court settlement, are indicative of its commitment to future transparency. But it acknowledged that the documents made for disturbing reading.

“We realize the information included in these documents is upsetting. It is painful to read. It is not the Church we know or the Church we want to be. The Archdiocese sincerely apologizes for the hurt and suffering of the victims and their families as a result of this abuse. Our hope is through this release of documents … we can help further promote healing among all those affected by these crimes,” the archdiocese said in a statement.

The documents were released to Jeffrey Anderson and Associates, a law firm in St. Paul, Minn., representing dozens of clergy victims. They involve 30 Chicago-area priests, the majority of whom were accused of abusing minors before 1988. Fourteen of the priests have since died and all were defrocked. “Today no priest with even one substantiated allegation of sexual abuse of a minor serves in ministry,” the archdiocese said.

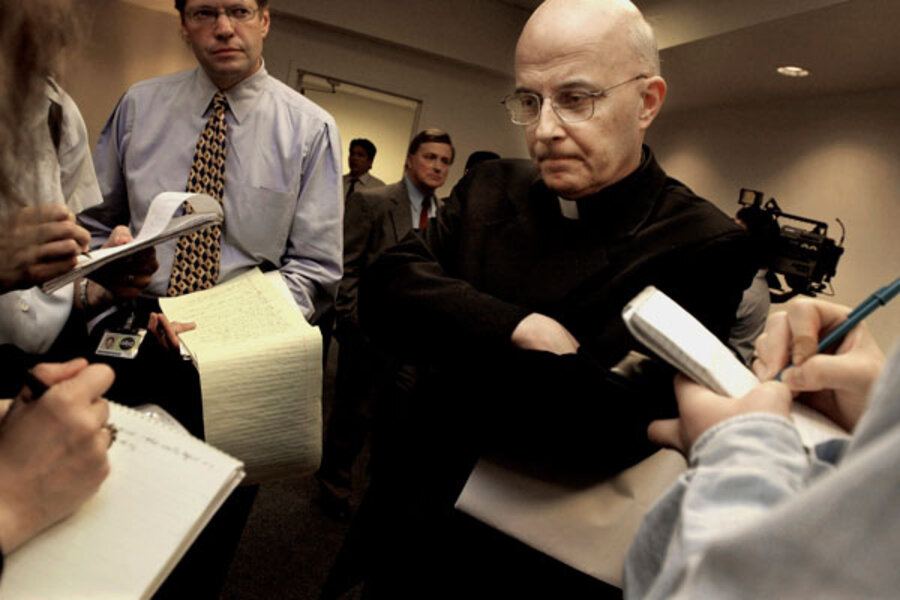

Victim names, medical history, and personal information was redacted, a process that took close to six years, says Bishop Francis Kane, vicar general of the archdiocese. Still, the documents shed light on how church leaders reacted to allegations of abuse against clergy members.

In one 1991 document, accused priest James Hagan was told that allegations made in May 1988 had no merit. “As far as [the commission was] concerned, the incident is closed.… Not to worry. We can put it away for good now,” he was told.

By 1997, however, Mr. Hagan had been removed from the priesthood, and in 2005, he was one of 14 priests accused of molestation. The church settled with 24 victims who were minors at the time of abuse for an undisclosed amount.

The documents could also influence the reputations of the late Cardinal John Cody and Cardinal Joseph Bernardin.

Cardinal Bernardin, in particular, was one of the most prominent activists against clergy abuse and in favor of reform. But in one set of documents, a victim letter from March 2002 alleges abuse from former priest Marion Snieg in 1958 and 1959, the year the abuse was first reported. An accompanying memo from Bernardin in 1987 suggests an awareness of the situation.

“I am encouraged, though, that [Mr. Snieg] was so candid with you. It does seem that everything is now under control,” he wrote.

Snieg retired in January 2002 and withdrew from ministry in May 2002. In October 2003, he was one of 11 priests accused of abuse by 15 victims. The case led to an $8 million settlement.

But experts don't see any bombshells in the documents.

“Bernardin’s reputation has suffered under this whole culture of secrecy, allegations, and, of course, way too many actual cases. Legacy-wise for him, and for Cardinal George, a lot of the damage at this point is already done,” says Bruce Morrill, a professor of Catholic studies at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tenn., and a Jesuit priest.

The archdiocese's Bishop Kane says past cardinals “cannot speak for themselves,” which makes it difficult to interpret their actions. He suggests that one reason for the inaction of past administrations was cultural.

“There has been a sea change in the way we look at so many different things in our society today than we did, say, in 1970. If you look at our understanding of domestic abuse, or sexual harassment, or date rape, they’ve all undergone significant change,” he says.

In a letter to the archdiocese in January, Cardinal George promised “more information in the future.” He explained that the priests named in the documents were allowed to remain in their posts because “the general discipline of the clergy weakened during the years when sex abuse was most prevalent.” Even when the archdiocese began taking allegations more seriously in the late 1980s, they did so “sometimes hesitantly.”

“Archdiocesan policy still allowed some perpetrators a restricted form of ministry, with monitoring, that kept them from regular contact with minors,” he explained. A zero tolerance policy took hold in 2002, which allowed him to remove priests against whom credible accusations were made.

Current policy dictates that all reports of sexual abuse are immediately reported to civil authorities.

To date, the Archdiocese of Chicago, the third largest in the US, has paid about $100 million to settle abuse allegations involving its priests. The archdiocese website lists 65 priests who were credibly accused of abuse; none is currently serving in the ministry.

Kane suggests that the documents show the archdiocese is serious about addressing child sexual abuse.

“We hope it will bring some healing to victims so they will feel they are having their story told. And we’re hoping we prevent future victimization of young people,” he says.

“We want and encourage people if they experienced an incident of sexual abuse as a child to come forward,” he adds. “Our church has been humbled, if not humiliated, by all that has taken place. But I hope by a more humbled church, we can serve people better to make sure we minister to victims and don’t create any more.”

Professor Morrill of Vanderbilt is “optimistic” about church transparency. The more difficult challenge for the church in the US is in rebuilding its credibility “to act as a moral and ethical teacher in American society.”

“There is a lack of credibility and in the immediate term, I don’t see that vanishing,” he says.