Uighurs' release from Guantànamo brings tragic ordeal to an end

Loading...

Tuesday’s announcement of the release of the final three Uighur detainees at Guantànamo brings to a close the tragic ordeal of a group of Muslims from China held at the controversial terror detention camp for years without any evidence of involvement in terrorism.

The three men were quietly transferred on Monday from the remote US Naval Base in southeast Cuba to Slovakia, which offered the Chinese nationals the opportunity to resettle there.

The three men are all members of the separatist Uighur minority in western China, which has been subject to persecution by Chinese officials. US law prevents the government from sending them back to China or any other country where they might face brutal treatment.

At one time, there were 22 Uighurs at Guantànamo. They were captured in Afghanistan in 2001 and sold by bounty hunters to the US military. The following year, they were moved to Guantànamo as suspected terrorists.

Later, intelligence officials determined that the Uighurs had no ties to Al Qaeda or terror groups and could be safely released. Despite that conclusion, China considered them dangerous, and many countries were reluctant to offer them resettlement.

In 2008, a federal judge ordered the US government to release the Uighurs, even if it had to admit them into the US. The ruling was reversed on appeal.

Nonetheless, the government continued to search for countries willing to resettle the Uighurs.

In addition to the three sent to Slovakia, arrangements have been negotiated with five other counties to accept the detainees.

Five Uighurs were sent to Albania in 2006. Six were sent to the South Pacific island of Palau in 2009. Four went to Bermuda in 2009. Two were resettled in Switzerland in 2010. And two were transferred to El Salvador in 2012.

The resettlement of the last Uighurs reduces the total number of detainees at Guantanamo to 155. It came a week after Congress eased restrictions on the transfer of detainees from the detention camp.

Detainee lawyers, human rights groups, and a Defense Department official hailed the transfers as another step toward the eventual closure of the facility.

President Obama pledged to close Guantànamo while campaigning for president in 2008 – a goal the president and his administration continue to embrace.

“This transfer and resettlement constitutes a significant milestone in our effort to close the detention facility at Guantànamo Bay,” Rear Admiral John Kirby, the Pentagon press secretary, said in a statement announcing the transfers.

Overall, 11 detainees have been transferred out of Guantànamo in 2013.

Dixon Osburn of Human Rights First sees the removal of the prisoners as a “promising sign that the administration intends to make good on its promise to close the Guantànamo detention facility.”

He noted in a statement that more than 70 of the remaining 155 detainees have already been cleared for release. But he warned: “If the administration does not vastly accelerate the review board process and complete all of them in 2014, President Obama will not be able to keep his promise of closing Guantànamo before the end of his second term.”

Within the population of detainees at Guantànamo, the three Uighurs were low-hanging fruit. Admiral Kirby noted that the three men had been subject to a comprehensive interagency review. “These individuals were designated for transfer by unanimous consent among all six agencies on the task force,” he said.

In contrast, roughly half of the remaining detainees at Guantànamo are being held for potential trial before a military commission or are being held because they are considered too dangerous to release. It remains unclear where those detainees would be housed should the Guantànamo detention camp be closed.

The Center for Constitutional Rights praised the transfer of the Uighurs and expressed gratitude to the government of Slovakia.

“This is a profound humanitarian gesture toward three men the US government long recognized were innocent of any wrongdoing and never should have been brought to Guantànamo,” the group said in a statement.

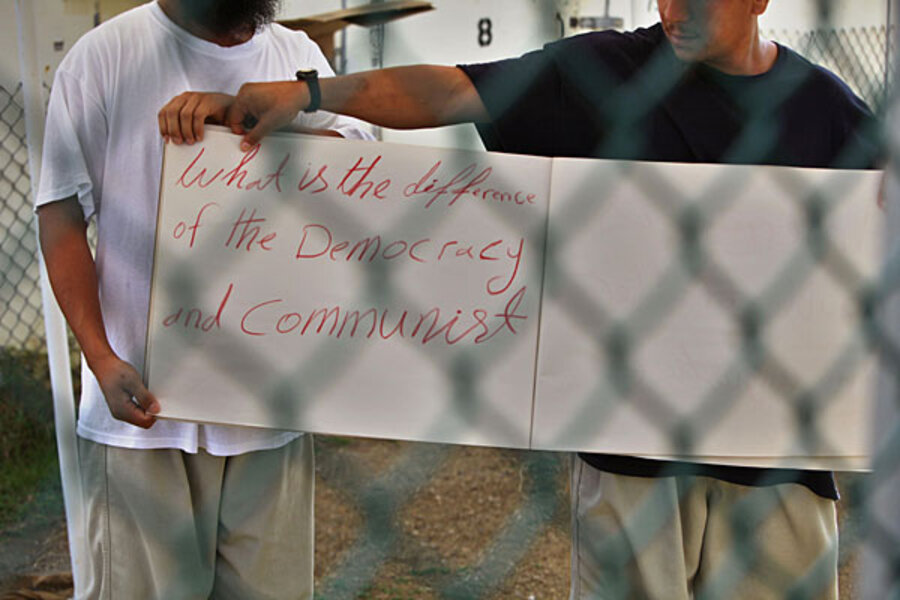

“Unfortunately, their release was delayed for a decade during which they endured terrible physical and psychological abuse at Guantànamo,” the statement added.

The CCR statement said the Uighurs had become pawns in a geopolitical chess match in which the US agreed to hold the Uighurs at Guantànamo in exchange for China’s agreement not to block a UN Security Council resolution in advance of the invasion of Iraq in 2003.