The aim of America’s war in Afghanistan was to make sure that the country was never again used as a safe haven from which terrorist groups might launch attacks on the US or its interests around the world. But a decade later, there are areas in northeastern Afghanistan, including the tough mountainous provinces of Nuristan and Kunar, where Al Qaeda groups are once again “establishing a foothold,” Jones says.

As the US prepares to end its combat role in the country by 2014 – and Pakistan continues to push for an end to drone strikes that have targeted top Al Qaeda leadership in its ungoverned tribal regions – the pressure on the terrorist organization is waning. “The growing concern I have is that as we cede control of more territory, Al Qaeda can use that territory for a resurgence,” Jones adds.

Indeed, after each wave of US successes against Al Qaeda – in western Anbar Province in Iraq, following the Sunni uprising, for example – “there have been predictions that Al Qaeda is largely dead,” Jones says. At the moment, however, as the Pentagon shifts its strategy towards Asia and, concurrently, prepares to send US Marines to bases in northern Australia, while pulling them out of southern Afghanistan, the US military is “in a bit of a bind,” he adds.

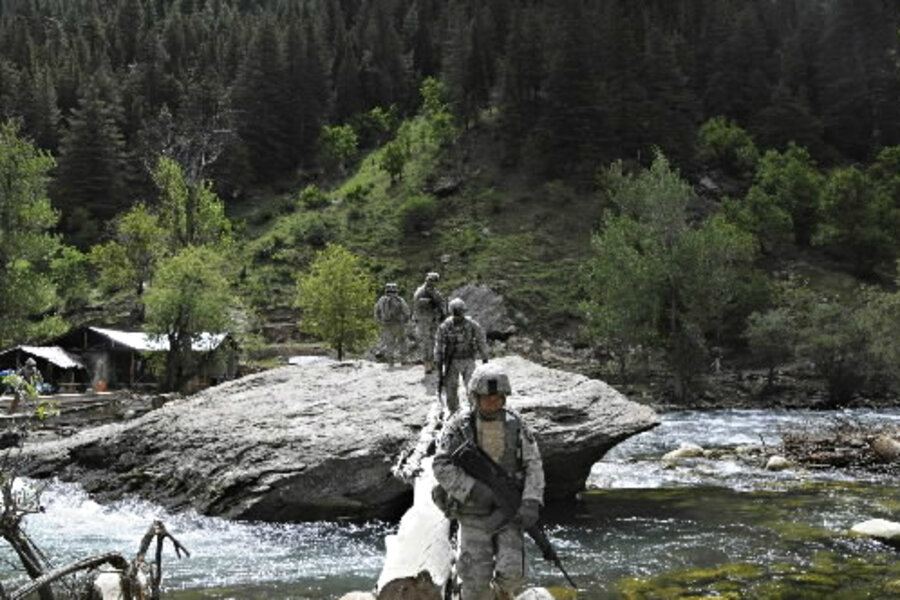

The solution may be working with tribal leaders through “village stability operation” teams of US Special Forces partnered with Afghan forces. “You don’t need large numbers of Special Operations Forces,” Jones says. “Just enough forces to maintain some influence on the ground – I think that’s frankly our best shot.”