The opioid epidemic may have started with a doctor's letter

Loading...

Nearly 40 years ago, a respected doctor wrote a letter to the New England Journal of Medicine with some very good news: Out of nearly 40,000 patients given powerful pain drugs in a Boston hospital, only four addictions were documented.

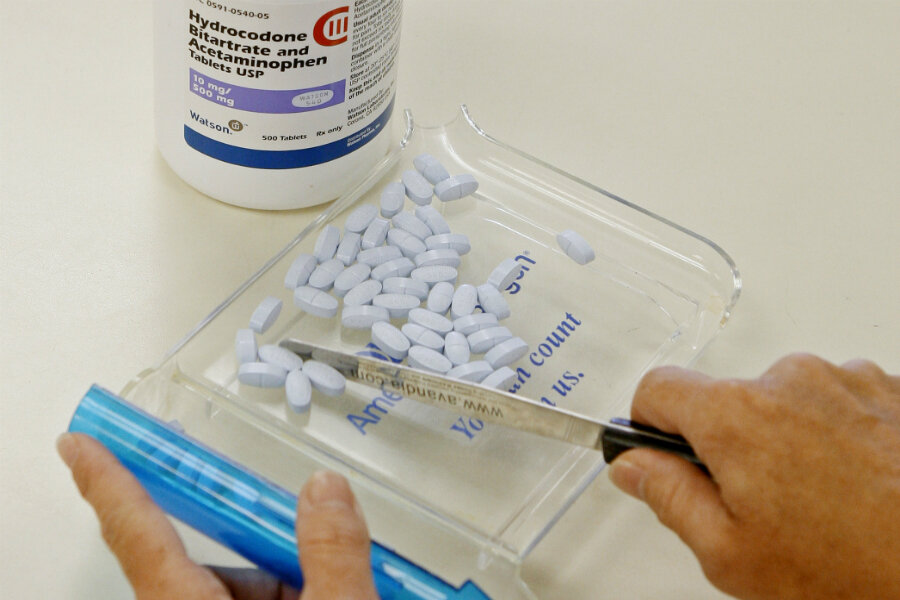

Doctors had been wary of opioids, fearing patients would get hooked. Reassured by the letter, which called this "rare" in those with no history of addiction, they pulled out their prescription pads and spread the good news in their own published reports.

And that is how a one-paragraph letter with no supporting information helped seed a nationwide epidemic of misuse of drugs like Vicodin and OxyContin by convincing doctors that opioids were safer than we now know them to be.

On Wednesday, the journal published an editor's note about the 1980 letter and an analysis from Canadian researchers of how often it has been cited – more than 600 times, often inaccurately. Most used it as evidence that addiction was rare, and most did not say it only concerned hospitalized patients, not outpatient or chronic pain situations such as bad backs and severe arthritis that opioids came to be used for.

"This pain population with no abuse history is literally at no risk for addiction," one citation said. "There have been studies suggesting that addiction rarely evolves in the setting of painful conditions," said another.

"It's difficult to overstate the role of this letter," said David Juurlink of the University of Toronto, who led the analysis. "It was the key bit of literature that helped the opiate manufacturers convince front-line doctors that addiction is not a concern."

Hospital databases were so limited in 1980 that we can't be confident there weren't more problems, or cases discovered after patients were discharged, Dr. Juurlink said.

The letter was written by Hershel Jick, a drug specialist at Boston University Medical Center, and a graduate student.

"I'm essentially mortified that that letter to the editor was used as an excuse to do what these drug companies did," Dr. Jick told The Associated Press in an interview on Wednesday. "They used this letter to spread the word that these drugs were not very addictive."

Jick said his letter only referred to people getting opioids in the hospital for a short period of time and has no bearing on long-term outpatient use. He also said he testified as a government witness in a lawsuit years ago over the marketing of pain drugs.

Use grew in the 1990s when drugs like OxyContin came on the market, and more people using opioids for chronic pain developed dependence.

The new editor's note in the journal says: "For reasons of public health, readers should be aware that this letter has been 'heavily and uncritically cited' as evidence that addiction is rare with opioid therapy."

The journal's top editor, Jeffrey Drazen, said, "People have used the letter to suggest that you're not going to get addicted to opioids if you get them in a hospital setting. We know that not to be true."

The journal also published a report from Francis Collins, director of the National Institutes of Health, and Dr. Nora Volkow, head of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, pledging to work with industry to develop new ways to reverse and prevent overdoses, to treat addiction, and to find novel, non-addictive drugs for chronic pain.

In the next six weeks, NIH will hold three workshops with drug company leaders to identify next steps, Dr. Collins said. The goal is to cut in half the usual amount of time to develop new treatments – a target borrowed from the Cancer Moonshot project launched by former Vice President Joe Biden to make a decade's worth of progress toward cures in half that time.

Details have not been worked out, but it could resemble similar partnerships on Alzheimer's, diabetes, and some other diseases where scientists from government and industry determine pressing needs, develop a work plan, and split the cost, Collins said.

"Industry's interest in this has been muted until recently," Collins said. Now, "they feel the responsibility and the opportunity to take part in this and they're not going to stand back and watch."

With the Food and Drug Administration wanting to speed work on new pain drugs, "the stars are aligning," Collins said. "I think we can make real progress now."