Of comic books and Canaletto

Loading...

I’m not an art expert, or a historian, so I’m not the one to judge how the paintings by Canaletto’s nephew, Bellotto, compare with the more famous work of Canaletto. But I’ve been struck by how often in my travels a question occurs to me in one place, sticks in my mind, and gets answered years later and far away. If I were a better researcher I might find answers more quickly, but letting them arrive when they happen to do so may be more fun.

In the summer of 1998 my wife and I spent a few weeks teaching English conversation in a children’s summer camp in rural eastern Poland. The trip was organized by Global Volunteers, and we were privileged to stay in the summer home of the Polish winner of the 1924 Nobel Prize in Literature, Władysław Reymont.

The children had studied English in school, and could read it fairly well. My group of 10- to 12-year-olds also knew geography far better than pupils their age in the United States: They knew not only the state capitals, but also the names of all the principal rivers and capes along the coasts of North America. However, their conversational skills were weak. While the communist government was gone, few of their teachers had as yet traveled or studied in English-speaking countries.

Among other things, I brought a stack of Donald Duck comic books. My students enjoyed reading them and talking about Donald’s adventures. Comic books are wonderful aids for learning languages. Unlike newspapers and history books, they use conversational language. They also have pictures to help students reconstruct what the words mean.

Sometimes pictures allow another sort of reconstruction.

One weekend that summer, my wife and I visited Warsaw. Much of old Warsaw was destroyed in World War II and was reconstructed afterward. In a room in the rebuilt Royal Palace, a guide told us that all the exquisite pictures that lined the walls of that room from floor to ceiling had been painted by the Italian artist Canaletto. These paintings had a special place in Warsaw’s history, the guide added.

Canaletto had been hired by the King of Poland in 1768 to paint all the principal sites of downtown Warsaw. At the start of World War II, these extremely valuable paintings had been buried, then dug up after the end of the war. When the old downtown was rebuilt, the Canaletto paintings had been used as a guide to reconstruct the facades to make the old streets look as they had in the late 1700s.

It was a wonderful story, but it raised questions. We’d never heard of Canaletto traveling to Warsaw. We’d never seen paintings by Canaletto of anything other than Venice, Italy. Our limited knowledge of art history didn’t suggest how to research this, beyond a single source, which told us that Canaletto had worked in England for a few years when a war disrupted painting sales in Italy.

But then in 2010 a local museum, the Memphis (Tenn.) Brooks Museum of Art, had a traveling exhibit come to town: “Venice in the Age of Canaletto.” The paintings were naturally of Venice, but there was also a talk by the curator, which provided an opportunity to ask our questions. Had Canaletto ever visited Warsaw? Had he painted pictures there?

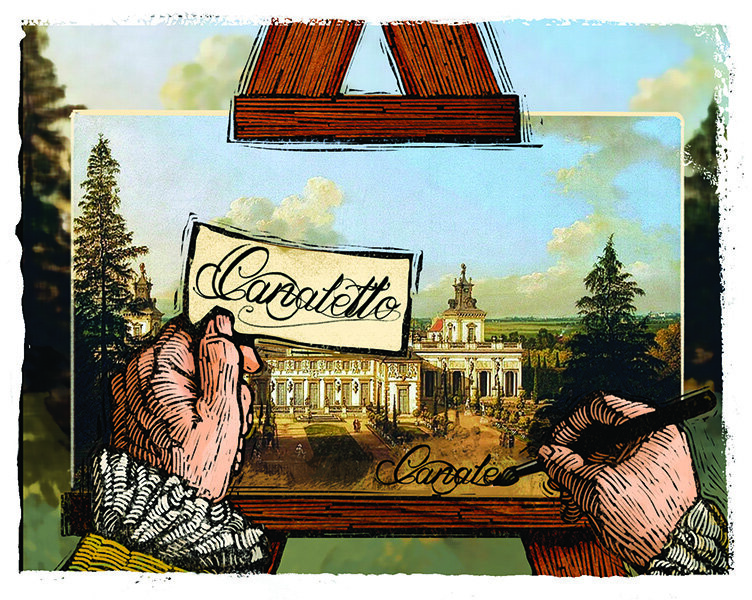

The curator was quite sure the answer was “no” to both questions, but he knew how to research the matter and found an explanation. Canaletto, whose name was Giovanni Antonio Canal, had a nephew, Bernardo Bellotto, who studied under him. Bellotto mastered Canaletto’s style very well – so well that when he had finished his studies, he could produce Canaletto-style paintings in such quantity that there was not enough of a market in Venice for both his paintings and Canaletto’s.

Canaletto remained in Venice, and Bellotto traveled around Europe. Apparently, Bellotto often introduced himself as Canaletto and even signed that name to his paintings.

I do not know whether the King of Poland, who employed Bellotto from 1768 to 1794 to paint those scenes of historical Warsaw, was misled as to the identity of the painter. I don’t know enough about 18th-century law, or his arrangement with Canaletto, to know if Bellotto did anything improper.

After all, quite a few artists (employed by the Disney company) have drawn Donald Duck. But I’m very glad that Bellotto’s work survived to help rebuild Warsaw.