For kids: The strangest worm you'll never see

Loading...

In the Pacific Ocean near the Galapagos Islands, deep below the surface in the black and silent depths, there lives an animal so strange, so peculiar, so fundamentally different than all other animals that it could be an alien from another world. And in a way, it is.

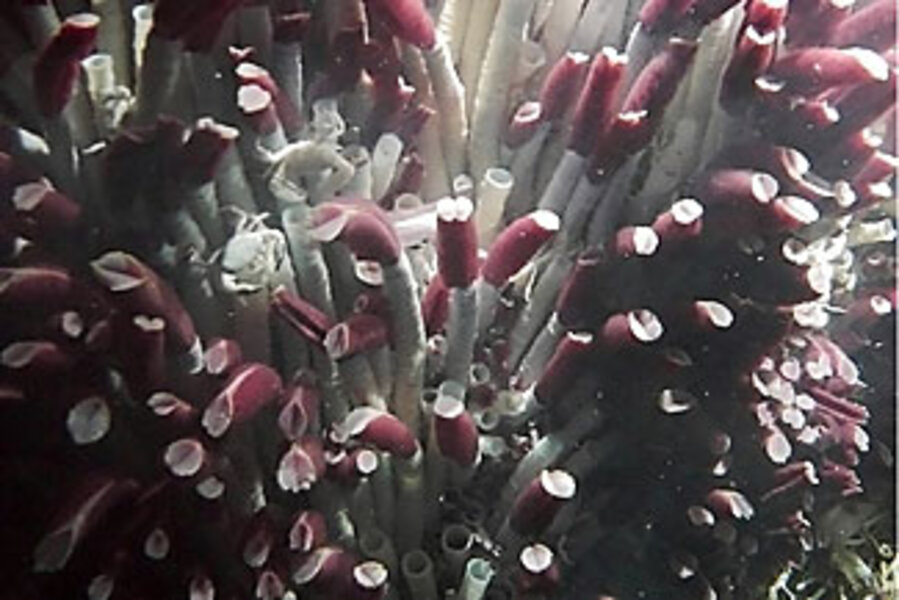

Its name is Riftia pachyptila (riff-TEE-ya pak-ihp-TIL-ay) – the giant tube worm – and until 1977 scientists didn't even know it existed. Capable of growing eight feet long, the giant tube worm has no mouth, stomach, or intestines. It has no eyes, but it doesn't really need them – it lives in pitch darkness. Its soft body is housed inside a protective white tube made of chitin (kahy-tin), the same substance found in the shells of shrimp and crabs.

The worm's most distinctive feature is its bright red plume. Like a fish's gills, it is a specialized organ that absorbs chemicals from the surrounding seawater. The plume's feathery tissues are filled with a special hemoglobin, which is a protein that helps blood cells carry oxygen. Iron dissolved in the hemoglobin gives the plume its color.

Giant tube worms don't crawl like backyard worms. They anchor their bottoms to rocks and extend their red plumes into the current. Gathering in thousands atop rocky outcroppings, giant tube worms form dense colonies.

Tough neighborhood

When scientists aboard the mini-submarine Alvin first saw the giant tube worms, they couldn't understand how such large animals could live more than a mile beneath the ocean surface. Up until that time, the deep oceans were thought of as deserts because of their hostile environments. The water is just a few degrees above freezing. The pressure is crushing. The weight of 8,000 feet of seawater presses down with the force of thousands of pounds per square inch – enough pressure to crush metal. And it is dark. The deep oceans are beyond the reach of sunlight. Photosynthesis, the process plants use to turn sunlight into glucose, a food source, can't occur in darkness. No sunlight means no plants. Without plants, the only food available to deep ocean residents are tiny bits of plant and animal matter that drift down from the surface. Large animals like giant tube worms should starve.

And yet, there they were. Not only were giant tube worms living in a desert, but they were living without an obvious source of food. Even more mysteriously, they were living next to deadly hydrothermal vents.

Hydrothermal vents are undersea geysers. They form where tectonic plates pull apart and open cracks in the seafloor. Seawater pours hundreds of feet down into these cracks, where it is heated by volcanic magma. The heated seawater erodes surrounding minerals, creating an acidic, mineral-rich fluid, as black as ink and superheated to more than 600 degrees F. Pressure forces the fluid up though the cracks, where it is ejected into the surrounding seawater.

Vent fluid is not only scalding hot, it's poisonous. Trapped within the fluid are high concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane, and hydrogen sulfide, the gas that gives rotten eggs their smell. These gases are dangerous. No animal should be able to live near them. But the tube worms, living right next door, were thriving. It made no sense.

There are blizzards at the bottom of the sea, but the flakes aren't snow. They're bacteria. Billions swirl around in blinding snowstorms that settle on the seafloor in slimy white mats several inches thick. Scientists noticed that mats of heat-loving bacteria called thermophiles were common near "black smoker chimneys," which are tall, stalagmite-like structures made from the dissolved minerals in vent fluids. Scientists knew that certain types of bacteria could live without oxygen or sunlight. But could they live without food?

To their surprise, scientists found that the bacteria living near the vents were using hydrogen sulfide as a food source. Unlike nearly every other organism on earth, these vent bacteria weren't surviving on sunlight, plants, or photosynthesis. They were making food from chemicals. Scientists began to suspect that the bacteria, the vents, and the tube worms were connected.

Partners with bacteria

When scientists examined the tube worms, they made an unexpected discovery. A specialized organ inside the worm's body contained billions of vent bacteria, so many that it accounted for half the worm's body weight. The mystery was solved.

Housed inside the worm, the bacteria had a stable environment close to its food source – the vents. And thanks to the worm's red plume, which absorbs chemicals from the water, it had a steady supply of hydrogen sulfide for food. And in return, the bacteria used the chemicals provided by the tube worm to produce carbohydrates and proteins that fed the worm.

Giant tube worms are more than strange, they're revolutionary. Their existence confirms that life is possible even in the most extreme environments. It has led scientists to wonder what other creatures are lurking out there.