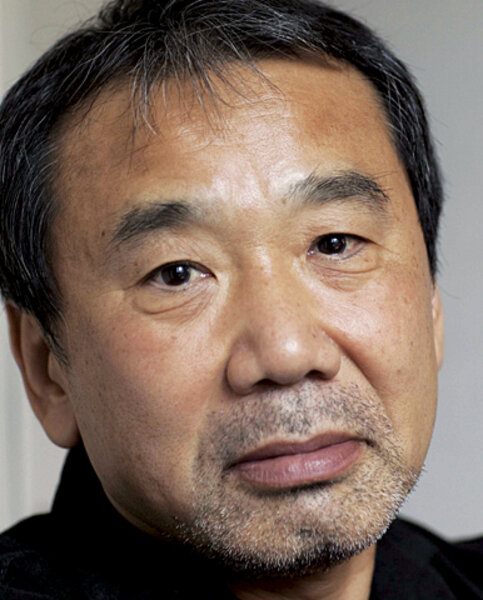

Japanese writer Haruki Murakami's prescient fiction

Loading...

In Haruki Murakami's world, fish fall from the sky near a Tokyo train station, backyard wells lead to personal and political violence, and a giant frog tells a businessman how to save Tokyo from its next major earthquake. The mundane mingles with the absurd, but neither offers solutions in a universe bent toward chaos.

Mr. Murakami cites Franz Kafka as one of his major influences, yet he warms Kafka's chilly detachment with Japanese earnestness, producing novels that anticipate apocalypse without succumbing to easy cynicism. In Murakami's world, chaos is softened by empathy – a quality in sorrowfully short supply, in fiction or in reality, in our 21st century.

"Everything is uncertain," muses Tengo, the male protagonist of Murakami's forthcoming novel, "1Q84," "and ultimately ambiguous." In Murakami's world, uncertainty is the norm. But once you accept it, his stories suggest, you can live and love accordingly.

Murakami's native land, Japan, has honed apocalyptic narratives by necessity. The only nation to have been victimized by the atomic bomb in 1945 is an archipelago slightly smaller than the state of California, subject to typhoons, volcanoes, earthquakes, and tsunamis – the latter of which recently destroyed the homes and livelihoods of much of its northeastern population. The brutal irony of the nation's embrace of nuclear power after its World War II blasts was summarized by Murakami himself during an awards speech in Barcelona this spring: "The accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant is the second major nuclear detriment that the Japanese people have experienced," he said. "However, this time it was not a bomb being dropped upon us, but a mistake committed by our very own hands.

"Yet those who questioned nuclear power were marginalized as being 'unrealistic dreamers.' "

Murakami may well have been talking about himself. Throughout his career, he has been marginalized by his generation, Japan's "boomers," many of whom abandoned political causes when the country's economic juggernaut seemed a sure thing. Living abroad, he heard a lot about his country's wealth and technology but nothing about its culture. "[My generation] was arrogant," he says now. "We believed that the future would always be better, but that's not true."

In his fiction, Murakami depicts a Japan of near-stifling mundanity. His protagonists are frequently bored and self-abnegating chumps whose lives are pierced by the supernatural, leading them to encounters with the darker forces of history, sexuality, and war. "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle," his sprawling 1998 novel, begins with its unemployed hero boiling spaghetti and whistling to Gioachino Rossini's "The Thieving Magpie." Suddenly his cat disappears, his wife leaves him, and he is drawn into a horrific confrontation with Japan's massacres in China.

The shattering impact of the natural and man-made disasters of March 11 in Japan is well suited to Murakami's world, where passive acceptance of the way things seem leads to the violence of the way things are. His generation's blind faith in the future and the ultimate good of technology is being severely tested, with an ongoing nuclear disaster serving as a persistent reminder of "mistake[s] committed by our very own hands." Tellingly, Murakami's readers in Japan tend to be younger than he ("I get older and my readers get younger," he often says), perhaps because they can see what his own generation has chosen to ignore.

Unrealistic and dreamy, Murakami's first novel, "Hear the Wind Sing" (1979), won him Japanese literary magazine Gunzo's prize for rookie writers and launched his literary career. His fifth novel, "Norwegian Wood" (1987; Knopf, 2000), now a motion picture from Anh Hung Tran, won him 2 million readers in Japan – and launched him into a white-hot spotlight. Murakami's reputation for aloofness grew over the years as he studiously avoided Japanese media and literary circles – partly, he says now, because he was shunned by his nation's literary critics for producing a bestseller.

Translator Jay Rubin recounts how Nobel laureate Kenzaburo Oe lambasted Murakami for "failing to appeal to intellectuals with models for Japan's future." With his interspersed references to American popular culture (the Beach Boys, McDonald's, etc.), Murakami was accused of being batakusai, or "stinking of butter": too American to be purely Japanese.

"They hated me," Murakami says of his Japanese critics, "and so I left."

His success, and the attention it brought, propelled him abroad, and his own life might be the subject of a road movie if he weren't so frankly unimpressed by it. He left Kobe for Tokyo at 18, and left Japan for Europe and America as soon as he could, he says, "because I wanted to write something international. And I still do. But I've just been feeling insecure since I was 20, and that's all I've been trying to express. Now the entire world is feeling insecure."

The roots of Murakami's insecurity, his outsider status, are local. When the Tokyo antiwar protests collapsed at the end of the 1960s and the formerly antiauthoritarian peaceniks quickly and obediently joined Japan's large corporations, the young Murakami felt betrayed. To avoid becoming another salaryman, he borrowed money and opened a jazz bar with his wife.

"Those were hard years," Murakami says, rubbing his chin. "But I learned discipline in those years, how to save money, and how to use time wisely."

Japan's current predicament feels eerily anticipated by Murakami's latest novel, "1Q84," in which twin protagonists, a male writer and female assassin, are reunited through the power of a novel and the seduction of a cult while the world they inhabit – "1984," or "1Q84" (the "q" being both a homonym for the Japanese word for '9' and also denoting a question) – melts into a very uncertain reality.

"The world is very chaotic today," Murakami says. "You have to think about so many things – your stock options, the IT industry, which computer you should buy, junk bonds. You have 54 channels on DTV. You can know anything you want from the Internet. It's so complicated, and you feel lost. But if you enter a small, closed circuit, you don't have to think about anything. The guru or dictator will tell you what to do and think. It's simple. So people like to enter those small, closed systems – just like the very intelligent people who gather in Aum Shinrikyo [the Japanese terrorist cult that poisoned Tokyo subways in 1995]. But once you enter that system, you cannot escape. The door is closed."

Murakami's world is about seeking the openings amid closed-circuit systems, a way out of the oppressive structures that civilizations build around their individuals. His world increasingly feels like a stand-in for ours – whether his readers are Japanese, Americans, Europeans, or other Asians – where globalization has made borders more porous but also less reliable. Surely that is part of his immense global appeal. While other novelists strive to keep pace with the headlines, Murakami has always seemed both below and ahead of them, writing from a source beneath our immediate perceptions and crafting narratives that force us to confront our secret selves.

Fiction, he told his audience in Israel in 2009 when he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize, the nation's highest literary award, garners its power "by telling skillful lies – which is to say, by making up fictions that appear to be true. The novelist can bring a truth out to a new location and shine a new light on it. In most cases, it is virtually impossible to grasp a truth in its original form and depict it accurately. This is why we try to grab its tail by luring the truth from its hiding place, transferring it to a fictional location, and replacing it with a fictional form. In order to accomplish this, however, we first have to clarify where the truth lies within us. This is an important qualification for making up good lies."

"1Q84" is a novel that weaves good lies into a simple truth: We reside in a world of uncertainty, and we better learn quickly how to live and love in it.