Why World of Warcraft won't let fans play their own game

Loading...

A dispute between fans and creators of one of the world's most popular video games raises questions about legacy, destiny, and intellectual property ownership.

Fans of the original World of Warcraft are calling for Blizzard Entertainment to set up new servers for the game's older version, known as "vanilla," after a popular fan server still offering it was shut down, the BBC reported. The company says it is not unwilling to indulge fans' interest in the simpler version, but cannot let the fan server, Nostalrius, go unchallenged without jeopardizing its own legal rights.

"The honest answer is, failure to protect against intellectual property infringement would damage Blizzard's rights," community manager J. Allen Brack wrote on the World of Warcraft website. "This applies to anything that uses WoW's IP, including unofficial servers. And while we’ve looked into the possibility – there is not a clear legal path to protect Blizzard's IP and grant an operating license to a pirate server."

Intellectual property law generally requires copyright holders to show that they are taking steps to protect their property. If someone with more nefarious intentions than these World of Warcraft enthusiasts were exploiting Blizzard's work, the company would be hard-pressed to claim it had defended its work while permitting legions of fans to pirate the classic game version on Nostalrius.

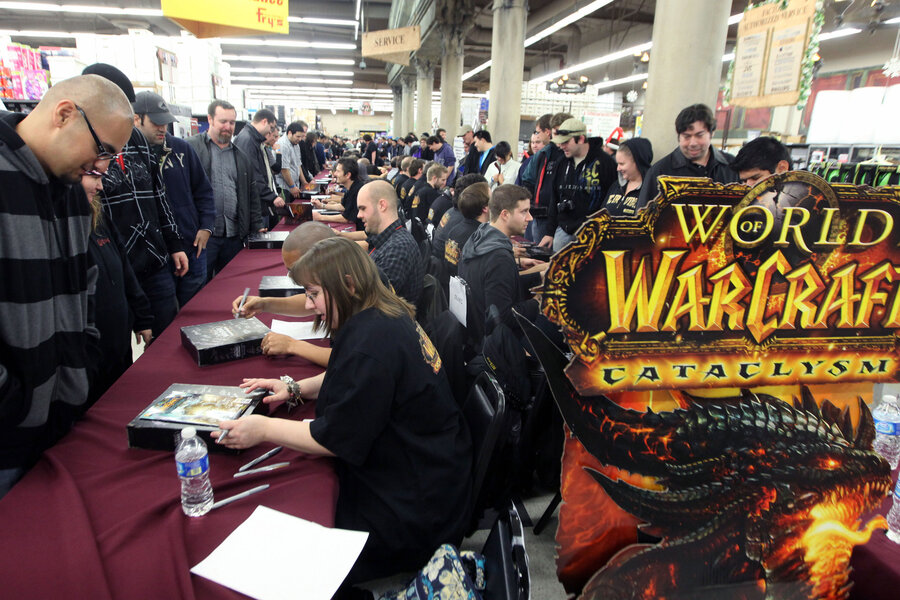

World of Warcraft, which is set for its sixth expansion release in August, debuted in 2004 and is one of the world's most popular video games, Engadget reported. As a massive multiplayer online game, World of Warcraft built an online community that hit 12 million subscribers in 2010, though it has since declined to 5.5 million.

Former World of Warcraft team leader Mark Kern has tried to forge a path through the copyright maze by playing the role of go-between. In an open letter to Blizzard Entertainment on YouTube, Mr. Kern said the developers of Nostalrius are "good people" motivated by "love for the game." They offered, he said, to provide programs and help to Blizzard if the company would develop an official legacy version.

"WoW is also an important game, it's part of gaming history, but there is no legal way for people to enjoy its earlier versions or to see where it all came from," Kern said. "Unlike the old days, they can't just boot up a floppy disk or slip in a CD-Rom. The original game is gone from the world forever, and legacy servers are the only way to preserve this vital part of gaming culture."

The debate has not come without dramatic moments – including a Distributed Denial of Service cyberattack immediately following the Nostalrius shutdown – but Blizzard said developers are working out the technical issues involved in creating a "pristine realm" without certain updates, Forbes reported.

Some players pointed to a "Project 99" for EverQuest, a private server project officially acknowledged by Sony Online Entertainment in April 2015, as a possible path through the legal issues.