Error 451: How to tell when websites have been censored

Loading...

If you’ve ever tried to visit a webpage that’s no longer available, you’ve seen the “404 Not Found” error alerting you that the sever can’t find that page. The “404” part of that message is an HTTP status code, one of a collection of standard codes that provide information about data transfers to your web browser.

As of last week, there’s a new status code indicating that a site can’t be accessed – not because of a broken link, but because the content is being blocked by a government.

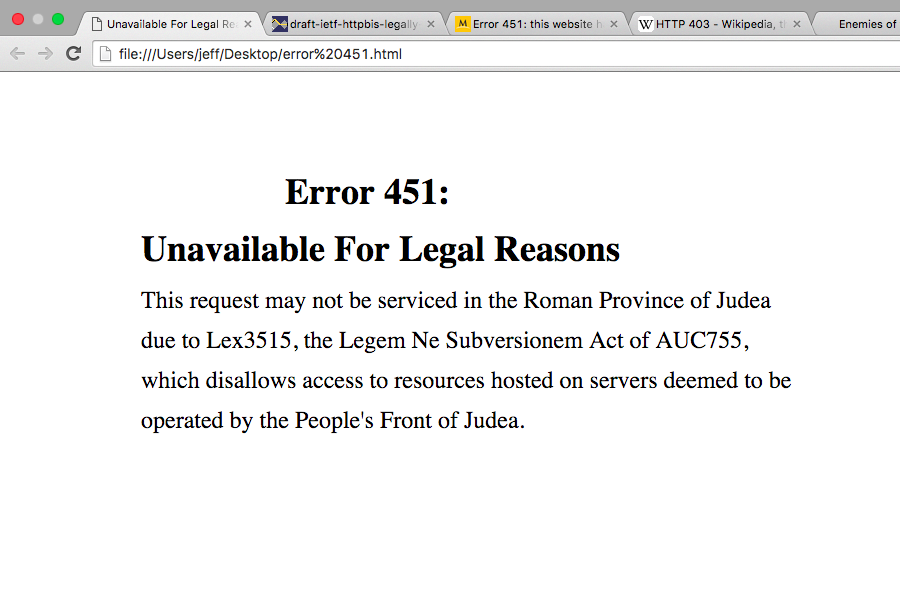

The code, Error 451, is a nod to Ray Bradbury’s 1953 dystopian novel “Fahrenheit 451” about book burning and the suppression of ideas. It tells the user that the site he or she is trying to access is working and reachable, but that they’re being prevented from accessing it for legal reasons.

Websites are governed by a patchwork of national and international legal systems, and it’s not always clear why a particular site is being blocked. The author of the specification, XML co-inventor Tim Bray, argues that Error 451 should also return some text about what authority is blocking the site, and under what law.

The idea for the code came about back in 2012, following a UK High Court ruling that directed British Internet providers to block The Pirate Bay, a popular file-sharing website. In order to comply with the ruling, some providers showed error code 403 (“Resource Forbidden”) to users trying to access The Pirate Bay, which gave Mr. Bray the idea of creating a separate error code to indicate censorship.

Error 451, which was approved last week by the Internet Engineering Steering Group (IESG) and can now be implemented by developers, is meant to “provide transparency in circumstances where issues of law or public policy affect server operations.”

The new code is optional – governments won’t be bound to disclose why, or if, they’re censoring particular sites.

“Certain legal authorities might wish to avoid transparency, and not only demand the restriction of access to certain resources, but also avoid disclosing that the demand was made,” Bray writes in the specification. But the code can also be implemented by sites themselves, giving frequently-censored companies such as Google, Github, Facebook, and Twitter a way to let the user know they're being blocked.

The most famous example of Internet censorship is China’s so-called “Great Firewall,” which blocks users within the country from accessing websites the Chinese government finds politically objectionable. Each year, Reporters Without Borders, a freedom of information nonprofit, publishes an “Enemies of the Internet” list in which it identifies governments and agencies that censor the Internet most heavily; last year’s list included Pakistan’s Telecommunications Authority, China’s State Internet Information Office, and the US’s National Security Agency, which the group criticized for its extensive online surveillance.