With ad blocking on the rise, publishers eye a new approach: asking nicely

Loading...

It’s no great secret that most commercial online content, including this newspaper, is sustained by advertising. Newspapers and websites generally offer paid digital subscriptions (which usually remove ads and offer other benefits), but circulation rates have been on the decline for years. In order to keep producing content, sites need to make up the shortfall by showing ads to their visitors.

The problem is that even though digital advertising revenues are on the rise, everyone hates online ads.

Many people get creeped out by how much personal data, including browsing and shopping habits, gets shared with advertisers. And there are legitimate privacy concerns about whether online visits can be linked to personally identifiable information such as a home address or a Social Security number.

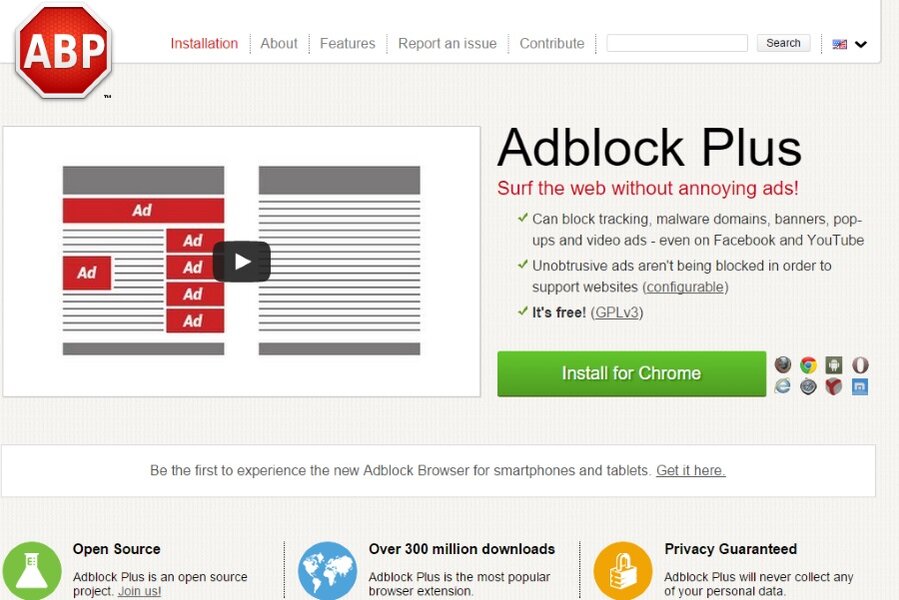

For many users, the solution is to install an ad-blocker. The software has been around for years, but lately its use has exploded – more than 15 percent of users in the United States use some kind of ad-blocking software, compared with just 8 percent in July 2013, according to Dublin-based media firm PageFair. Ad-blockers prevent digital ads from loading in the headers or sidebars of websites you visit, making Web surfing more speedy and arguably more secure.

Here’s the catch: in many cases, ad-blockers also starve sites of the revenue they need to survive. PageFair estimates that ad-blocking will cost publishers $22 billion in lost revenue in 2015, hitting technology sites and social networks especially hard. Publishers have pushed back in various ways, including disallowing users from viewing their pages altogether if they’re running ad-blockers. But now they’re trying something new: asking politely.

For a while, if you visited Wired.com you’d see a message asking you to “Please do us a solid and disable your ad-blocker.” Visit the Guardian’s website and you’ll be greeted with a banner reading, “We notice you’ve got an ad-blocker switched on. Perhaps you’d like to support the Guardian another way?” and a link to donate to the paper. If you browse Reddit with your ad-blocker disabled, you’ll occasionally see a drawing of a moose in the space where an ad would normally be, with the caption, “Thanks for not using Adblock Plus [the most popular ad-blocking software]. Have a silly moose.”

It’s too early to tell whether publishers’ appeals to users’ mercy will be successful. PageFair says they’re not likely to have an effect, citing a study it performed in which only 0.33 percent of ad-blocking users allowed ads to be shown on sites that asked that ad-blockers be disabled. On the other hand, the New York Times’s Farhad Manjoo argues that “if blocking becomes widespread, the ad industry will be pushed to produce ads that are simpler, less invasive and far more transparent about the way they’re handling our data.” Users say they don’t mind ads that don’t track them, distract them with animations, or cover up the content they’re trying to view.