How Bartolomeo Cristofori, who invented the piano, changed music

Loading...

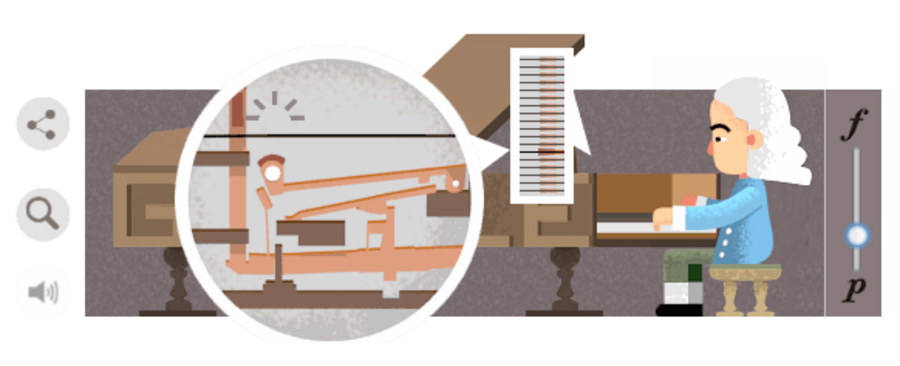

Monday's Google doodle honors the 360th birthday of Bartolomeo Cristofori, inventor of the piano. Despite the fact that Mr. Cristofori’s name is largely unknown, his greatest invention has been a hugely influential instrument in both music and society.

Cristofori was a famed musical instrument maker in Italy, who moved from Padua to Florence in 1690 to work for the powerful Medici family. It was in Florence that he invented his masterpiece. The first piano is thought to have been designed by the year 1700, although it took Cristofori an additional 17 years to create a version that had all the elements of the modern piano.

The most important challenge Cristofori had to overcome in creating the piano was designing a hammer mechanism that struck the strings within the piano’s body. This allowed the volume to be altered depending on how hard or light a player pressed the keys and proved to be a major breakthrough in music.

The doodle features Cristofori seated at a piano playing Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring,” a piece that was composed during Cristofori's lifetime. The piano in the doodle includes a window through which the curious Google searcher can see the internal hammer mechanism, as well as a slider that adjusts the volume between ‘piano,’ meaning quiet, and ‘forte,' meaning loud.

Prior to the invention of the piano, most music was composed on either the harpsichord, which was used for loud pieces, or the clavichord, which was used for quieter pieces. Although both were similar to pianos, they were not as versatile.

Pianos are now a universal instrument for composing music, largely because nearly every note a composer would ever need is present on its keyboard. The average piano has 7 octaves, therefore, composing music for instruments as low as the contrabassoon or as high as the piccolo can both be done on the piano.

“The piano has been extraordinarily influential,” Stuart Isacoff, who wrote “A Natural History of the Piano,” told the Monitor. “There was a time when almost every household had to own one, first in England and then in America. Nearly everyone in the West was learning and playing music. That contributed to the development of classical music ... and increased awareness of great music.”

The instrument is also frequently used to teach music theory and music classes to young children.

“It is accessible from a playing standpoint in that you don't have to hold it or blow it, so it is easy for young children to play,” Dominick Ferrara, an associate professor of music education at Berklee College of Music, says in an interview with the Monitor. “It also combines visual and spatial learning, so it is a great foray into music.”

Interest in learning the piano and piano sales have been falling for the last century, causing some to question whether the instrument has a future. However, Mr. Isacoff believes that it does, and Google hopes its doodle will draw attention to Cristofori’s work.

“We're always trying to find topics that are educational, fun, and surprising – Cristofori is an ideal topic,” says doodle designer Leon Hong in a question and answer with Google. “Hopefully after the doodle, people will think of Cristofori everytime they see a piano.”