Buzzworthy space rocks: Asteroid hunters prep for near miss

Loading...

| Cambridge, Mass.

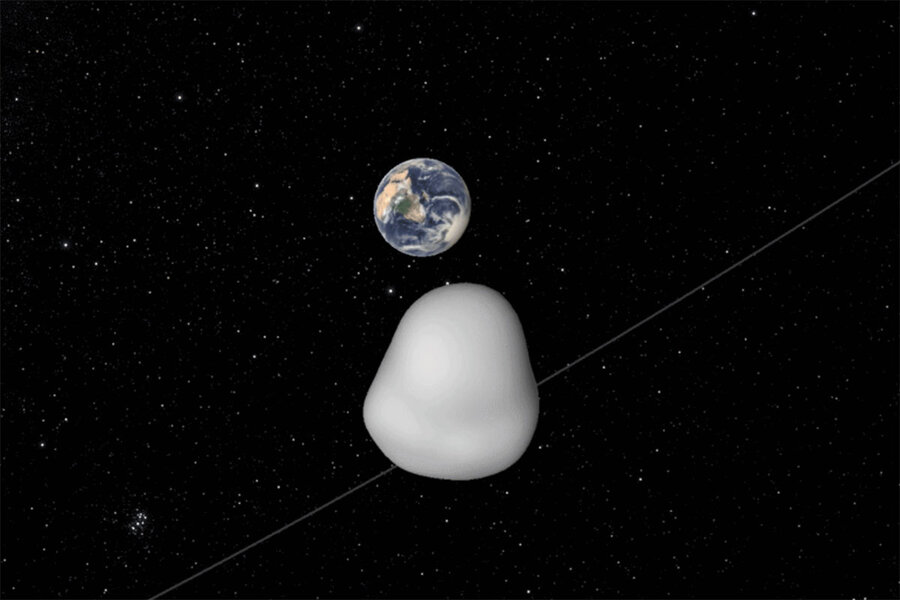

Dark, leisurely rotating, and traveling at about 30,000 miles per hour, asteroid 2012 TC4 is set for an Oct. 12 rendezvous with Earth.

The roughly 65-foot-wide space rock won’t hit us; astronomers calculate it will zip just 27,000 miles – one-eighth the distance to the moon – above our planet’s surface.

But the encounter highlights the threat meteors pose as well as astronomers’ urgent yet painstaking work to identify, track, and potentially deflect incoming space rocks.

“Things do hit other things, and we’re not special in that regard,” says Gareth Williams, associate director of the International Astronomical Union’s Minor Planet Center in Cambridge, Mass. “Just look up in the night sky and you can see things burning up in the atmosphere. Those are grains of sand.... Something the size of a car hits every few years.”

Astronomers have spotted most of the big ones. At the direction of Congress, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration launched a program in 1998 focused on finding 90 percent of all near-Earth objects (NEOs) larger than 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) wide. The asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 65 million years ago measured about 10 kilometers wide, but any impactor larger than 1 kilometer wide could trigger catastrophic climate change.

About 95 percent of those largest asteroids are now known, but in 2005 Congress directed NASA to expand its cataloging efforts to include NEOs larger than 140 meters (about 450 feet) wide. Scientists believe they have detected about a third of those so far. An impactor this size could cause local damage on land, and worse if it struck the ocean and triggered a tsunami.

“Impacts of large asteroids are extremely rare and therefore highly unlikely,” says Paul Chodas, project manager for NASA’s Center for Near Earth Object Studies in Pasadena, Calif. The odds of an asteroid 1 kilometer wide hitting Earth in any given year are 1 in about 500,000, and even an object 140 meters wide has just a 1-in-30,000 chance, he says. The larger the asteroid, the less chance of impact.

Asteroids do hit Earth frequently, but they’re small ones. About once every year, an asteroid 3 meters wide will strike our atmosphere, causing a spectacular fireball. Some particularly metallic rocks might make it to the ground, but they rarely cause damage.

But larger asteroids do pose a risk. The 2013 Chelyabinsk meteor, which injured nearly 1,500 people in the Russian city, was about the size of 2012 TC4. It had gone undetected before it slammed into Earth’s atmosphere, triggering a window-shattering shock wave.

What scientists need most to protect humanity from impact is time. The sooner astronomers find asteroids headed toward Earth, the better, Dr. Chodas says. “If the dinosaurs had a space program, they could have protected themselves, given enough warning,” he says.

Scientists are already working on ways to deflect potential impactors. A joint project between NASA and the European Space Agency called the Asteroid Impact & Deflection Assessment mission seeks to crash an unmanned spacecraft into the smaller body of a binary asteroid system in an effort to alter its course.

For now, astronomers are focused on finding as many asteroids as possible.

Dr. Williams says that more work needs to be done in spotting rocks like the Chelyabinsk meteor, which have struck Earth at least two or three times in the past century.

“On a human timescale, 50 years sounds like a long time,” he says. “But for mankind, 50 years hopefully is not a long projection to the future. So we really should be finding these things now so that we can ... reassure future generations that they don’t have to worry.”

“You probably want to ask me how I sleep at night,” he says. “I sleep very well, when the cats don’t disturb me.”