Schiaparelli's crash: What happened to the Mars lander?

Loading...

Schiaparelli left its mark on Mars – literally, it turns out.

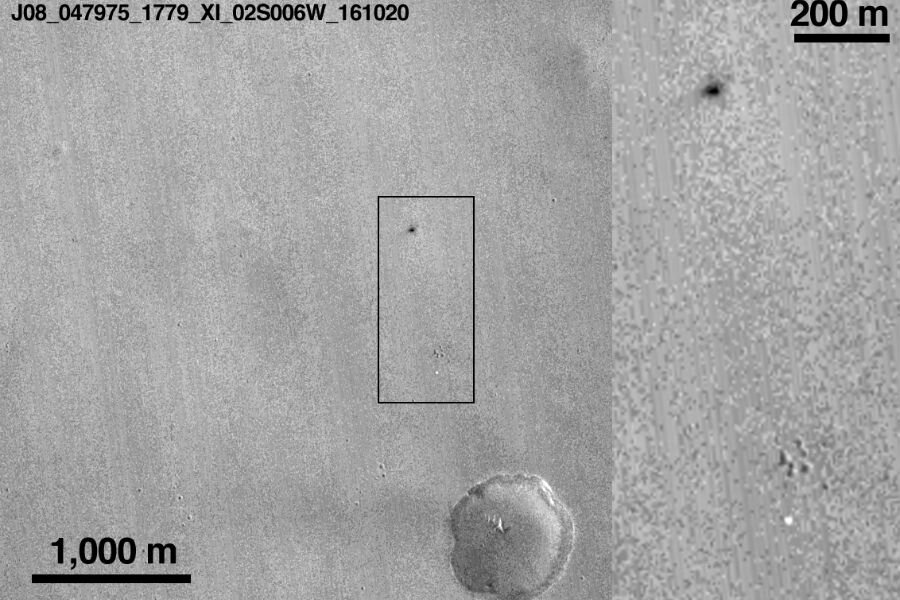

Close-up photos reveal that the Mars lander, a joint project between Europe and Russia, left a small crater on the planet’s surface. The images, taken by a NASA Mars orbiter and released by the European Space Agency on Thursday, support scientists’ theory that Schiaparelli hurtled toward the ground and then crashed at high speed.

For the European Space Agency, the photos are part of a full investigation that aims to figure out what went wrong with the probe’s Mars landing.

As the probe was too far away for its descent to be manually controlled from Earth, its engineers had programmed it to slow down during its six-minute descent to the planet’s surface.

Instead, it plowed into the ground at about 200 miles per hour, said ESA scientists, based on images suggesting that the crater is about 20 inches deep and almost 8 feet across.

To Mark McCaughrean, a senior science adviser at ESA, that suggests that Schiaparelli was confused when it landed, having assumed too soon that it was on the ground.

“Fundamentally there’s a software issue here between the radar and the on-board computer system,” he told the Associated Press. “The radar was giving inconsistent info on where it was.”

That may help explain other evidence spotted by NASA’s cameras. Half a mile south of the probe's crater, a white feature was observed. The object has now been identified as the parachute meant to slow Schiaparelli down after entering the atmosphere of Mars. It was still attached to the rear heat shield, and both were apparently ejected from the lander earlier in the descent than they should have been.

The photos also found an object almost a mile east of the impact site, consistent with the front heat shield being ejected as planned around 4 minutes into the descent.

Scientists are still trying to decode asymmetric marks around the crash site. If the crater had been made by a meteoroid with a low incoming angle, the ESA said, everything would make sense.

But Schiaparelli should have been descending vertically, so what could have created the marks? It’s possible that the propellant tanks exploded in one direction, throwing up debris from Mars’s surface, but scientists say they need to do more analysis to know for sure.

A full investigation is underway, said the ESA, to “avoid reaching overly simple or wrong conclusions.” Part of that investigation: gathering more data from Mars to interpret the features shown in these images.

Schiaparelli was the second European attempt to land on Mars, following the British "Beagle 2" mission that ended in failure back in 2003. The new probe was part of the ExoMars project, looking for life on Mars and designed as a trial run for the technology before the ESA puts a rover on Mars. That step is currently scheduled for 2020.