What spiral 'arms' around a star tell us about planet formation

Loading...

Spirals can be found throughout nature, from the smallest sea shells to the largest galaxies. As stars from from clouds of gas, the gravitational pull of a star will collapse the gases into a disk around it, often forming spirals in a manner similar to the galactic-scale disk of our own Milky Way.

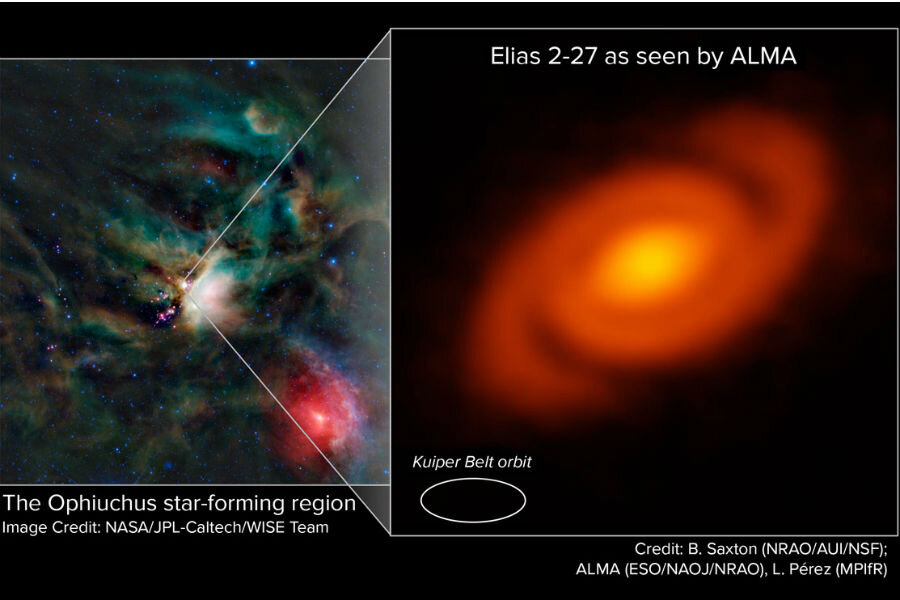

Scientists have observed these stellar spirals before. But the spiral around Elias 2-27 is a little different.

Elias 2-27 is a young star, at least a million years old and about half the size of our own sun. Yet the protoplanetary disk of gas spiraling around the star is unusually massive, and may hold clues about planetary formation, a subject that scientists still know little about.

"The standard theory of planet formation is called 'core accretion,' where a planet core grows out of smaller particles and planetesimals," study lead author Laura Pérez, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn, Germany, told Space.com. "Once the core is large enough, it quickly accretes gas from the disk and forms a planet with an atmosphere – think of Jupiter, with its massive inner core and then its massive atmosphere. However, this standard picture fails at large distances from the star. There are not enough dust particles and gas for core accretion to be proceed."

Scientists have observed spirals around stars like this before, but never with a star as young as Elias 2-27. Previous observations showed hazy spirals, often after planets had already formed, leaving scientists guessing about the early stages of the process.

The data for the phenomenon was gathered by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, and published in the journal Science. Among the data is the first ever high-resolution photo of the spiral disk around a star's mid-plane.

"When the project started, we wanted to see how the dust grain in these disks evolve with time," study co-author Adrea Isella said in a statement. "Planets start to form from micro-sized particles that stick together, and Laura and I thought we might be able to measure the size of the dust particles based on their distance from the star. If you look at two or three different wavelengths of light from the disk, then you can measure grain sizes as a function of radius. But when we got the data, we got this beautiful spiral."

The spiral structure is likely caused by the clumping of materials in a phenomenon known as density waves. Faster-moving matter gets caught behind slower-moving manner, causing "arms" in the disc to separate from each other. As the disk turns around the star, these arms curve, forming a distinctive spiral. This areas of density in the arms may help provide material for planetary formation farther away from the star than earlier models would indicate.

There's still a great deal of work to be done in order to understand what exactly is going on at Elias 2-27.

"Fortunately, the power of ALMA will be used in the future to answer this puzzle," Pérez told the National Radio Astronomy Observatory. "ALMA will further dissect this and other similar disks in an upcoming large program, helping astronomers understand the seemingly chaotic forces that eventually give rise to stable planetary systems like our own."