Smithsonian finds extinct river dolphin skull in its collection

Loading...

Sometimes, the most fascinating scientific discoveries happen not out in the field, but in dusty archives and museum boxes.

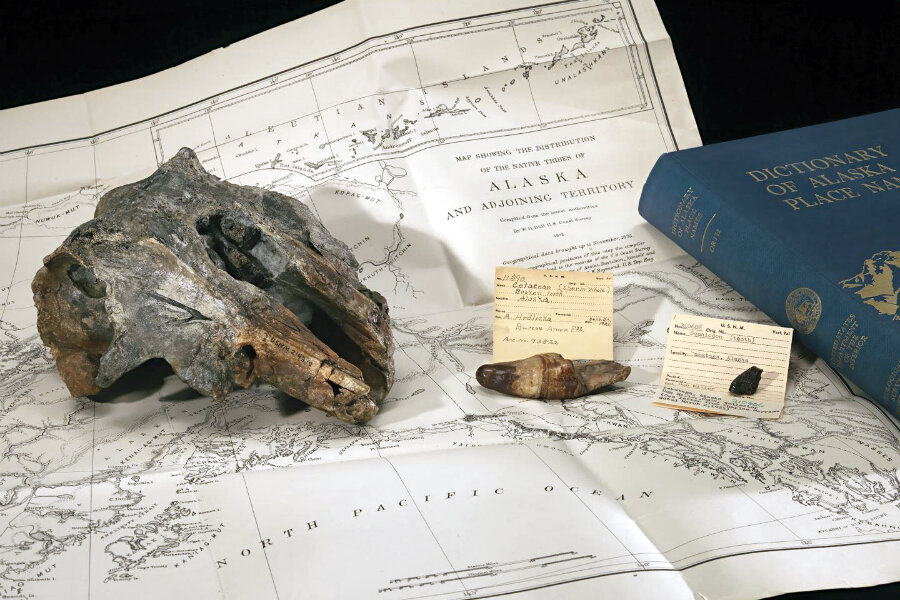

Smithsonian paleontologists have identified a cetacean skull, which had been left to the museum more than half a century ago, as belonging to an undiscovered species of prehistoric dolphin. The new species, described Tuesday in the journal PeerJ, may be a distant relative of modern South Asian river dolphins.

"All the time, we find new things in the collections that answer old questions," said lead author Alexandra Boersma in a statement.

A little more than 60 years ago, United States Geological Survey geologist Donald Miller was mapping Alaska's Yakutat borough when he came upon a damaged prehistoric skull. He shipped the specimen to the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, where it would remain for the rest of the 20th century. That is, until Dr. Boersma and fellow Smithsonian paleontologist Nicholas Pyenson found it in the museum archives.

Despite its broken snout, it was clear that the skull belonged to some type of ancient dolphin. The remarkably old fossil, researchers hoped, would answer questions about whale evolution in the Oligocene time period. The skull's place of discovery also enticed researchers: The fossil record of marine mammals is extremely limited at high-latitude areas such as Alaska, so this was a rare find.

And, as it turns out, a totally new one.

Boersma and Dr. Pyenson say the animal was likely related to platanistoids, the ocean-dwelling descendants of modern river dolphins. They named the new species Arktocara yakataga: Arktocara combines the Greek and Latin words for "north" and "face," and yakataga is the Tlingit name for the region where the fossil was discovered. Boersma and Pyenson dated the skull to 24 million to 29 million years old, and also made the specimen available as a 3-D model.

This isn't the first time a major discovery was made from an old fossil collection. In 2015, researchers from Imperial College London were able to extract intact blood cells from dinosaur bone fragments. The bones had been housed in the Natural History Museum of London for more than a century.

An unusual looking beaked whale that washed up on Alaskan shores in 2014 was identified as belonging to a new whale species. Further investigation revealed that skeletons of the previously misidentified whale already hung in Alaskan high school and another at the Smithsonian.

The dolphin fossil archival discovery is not the first for Boersma and Pyenson. In 2015, they announced a previously unknown species of ancient sperm whale from fossils found in Smithsonian storage. The animal’s massive jaws and teeth, discovered near Santa Barbara in 1925, had originally been identified as belonging to a walrus.