Did Pluto once have nitrogen lakes and rivers?

Loading...

New images from Pluto taken by NASA's New Horizons probe suggest that the dwarf planet's surface may once have had flowing rivers and lakes – of nitrogen, not water.

According to NASA, the nitrogen lake points to a time millions or billions of years ago when conditions on Pluto were far different from today. A thicker atmosphere would have raised the surface air pressure and temperature, creating an environment in which "liquids might have flowed across and pooled on the surface of the distant world," according to the space agency.

"In addition to this possible former lake, we also see evidence of channels that may also have carried liquids in Pluto’s past," said Alan Stern, a Southwest Research Institute scientist and principal investigator for the New Horizons mission.

Launched in 2006 with the mission of studying Pluto and other bodies in the Kuiper Belt – the vast disk of asteroids, dwarf planets, and comets that circle our star beyond Neptune's orbit – NASA’s New Horizons finally reached Pluto in July, when it began collecting detailed images and data on the icy body.

The spacecraft's tiny transmitter sent a few juicy tidbits back right away, but planetary researchers have had to wait for the vast majority of the images and measurements taken by New Horizons.

Over the past months, New Horizons has transmitted images of mountains coated in methane snow, "varied and complex" landscapes, and more, sending data through several billion miles of space to NASA scientists on Earth.

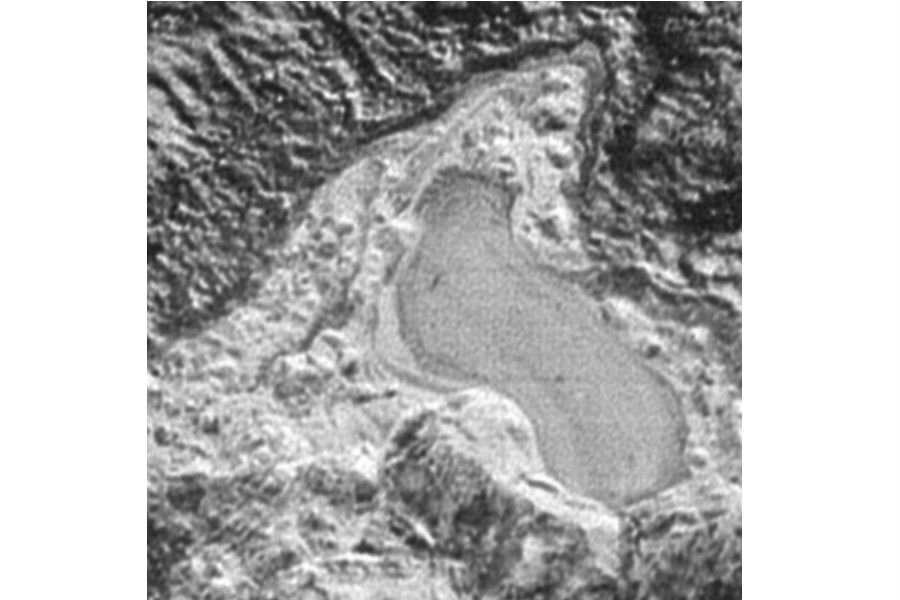

Now, scientists have found evidence of what appears to be a frozen lake of nitrogen. The Long Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI) on New Horizons snapped a picture last summer of the potential nitrogen basin. It is located north of the Plutonian region known as Sputnik Planum, a flat, icy plain bordered by mountain ranges where the lake was found, thought to be made up of nitrogen-based ice.

The craft’s imaging suggests that, at its widest, the lake stretched across 20 miles of Pluto’s surface. Its classification as a nitrogen lake has yet to be confirmed, Dr. Stern told New Scientist, but “it's hard to come up with an alternate model that would explain that morphology.”

The era of free-flowing nitrogen on Pluto appears to be over, thanks to the dwarf planet's environmental and physical evolution over time. Pluto, which takes 248 years to circle the sun, is "now in an intermediate phase between its climate extremes, with the last peak occurring less than 1 million years ago," reports Discovery.com. Today, surface temperatures dip to nearly 400 degrees Fahrenheit below zero.

But the New Horizons team believes that frozen nitrogen on the planetoid’s surface may be pressurizing lower layers enough to “have a liquid state at the base,” Orkan Umurhan of NASA’s Ames Research Center told New Scientist.

Dr. Umurhan estimates that liquid nitrogen on Pluto would have to be more than a half mile deep, although tests to confirm that possibility “haven’t been done yet in the laboratory.”

New Horizons is still sending back data from Pluto, while traveling on to the next phase of its mission. The probe will continue to analyze objects in the outer reaches of the solar system for years to come, and it is set to arrive at its next objective – Kuiper Belt Object 2014 MU69 – in 2019.

"We flew nine-and-a-half years and 3 billion miles to get to our target – the Kuiper Belt. Not just Pluto. The Kuiper Belt," Stern said, reported Spaceflight Insider. "New Horizons will be busy each and every year making multiple [Kuiper Belt Object] observations so that we really develop this fantastic data set by the end of the process.”