Scott Kelly: What happens after a year in space?

Loading...

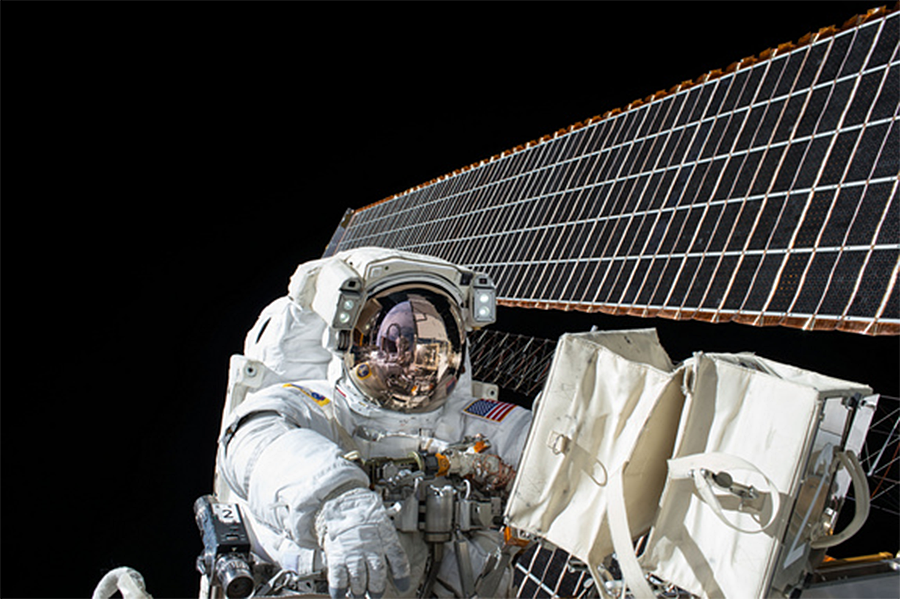

On March 1, American astronaut Scott Kelly and Russian cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko will return to Earth after spending a year aboard the International Space Station, in orbit 240 miles above Earth.

Mr. Kelly is the first American to stay in space for so long. Kelly and Mr. Kornienko are the first humans to do so since 1999, when Russian cosmonaut Sergei Avdeyev last spent a year in microgravity aboard the Russian space station Mir, according to NASA. The all-time record belongs to cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov, who spent 437 days on Mir from 1994-1995.

Though Kelly has been firing off tweets about the things he’ll miss most about space (sensational views of Earth, for one), he will probably be happy to plant his feet firmly on Earth and experience the grounding effects of gravity for a change.

He told CNN's Dr. Sanjay Gupta, it feels like he's spent his whole life on the station and that leaving it is going to be tough.

"I'll probably never see it again," Kelly told Gupta. "I've flown in space four times now, so it's going to be hard in that respect, but I certainly look forward to going back to Earth. I've been up here for a really long time and sometimes, when I think about it, I feel like I've lived my whole life up here."

But some aspects of his return may not be easy, his predecessors have pointed out.

"You've got this little bit of paranoia that you won't to be able to stand up when you walk home," Doug Wheelock, a NASA astronaut who spent 178 days in space over the course of two missions, told ABC News in June 2015.

"You feel the physiological changes when you get to space, and you are beginning to feel that your body and brain think you don't need your legs anymore," he said.

When Mr. Avdeyev returned to Earth from Mir in 1999, he was brought out from the spacecraft on a stretcher, The Guardian reported, as he was too weak to walk or even to sit up in a chair. It took a year for his body to readjust to full Earth gravity.

NASA expects Kelly to have a recovery period, but his recovery is precisely what scientists want to study.

After spending so much time in so little gravity, and in high radiation, researchers suspect that Kelly’s bones could be weaker, and his motor skills and vision impaired. But Kelly, like all ISS astronauts, exercises daily and has strategies for dealing with the effects of microgravity.

“We would be happy to see no difference in a six-month mission versus a year-long mission,” said John Charles, chief scientist of the NASA Human Research Program. “But we do anticipate changes."

Understanding how the body changes after one-year mission to space is instrumental to future human space missions, particularly long ones to Mars. By comparing Kelly’s condition post-space with that of his Earth-based, identical twin brother – retired astronaut Mark Kelly – scientists will for the first time be able to more clearly see the effects that space has on physical and psychological well-being.

“The mission will continue even after Scott returns,” said Dr. Charles. “The post-flight data are as important as the inflight data to help us learn how to send humans safely to Mars and return them safely to Earth,” he said.

But there is more to Kelly’s homecoming than physical adjustment and scientific experiments.

He will have also missed the simple pleasures of life that the ISS doesn’t offer. Kelly might crave his favorite food, or at least something that doesn’t come out of a plastic baggie. And fresh air is another luxury that doesn't exist aboard the ISS.

"Your sense of smell and taste are dulled in space,” Mr. Wheelock told ABC. “I craved the aroma of leaves and grass and flowers and trees … When you get back to Earth they are literally intoxicating," he said.

Despite some of the drawbacks of space travel, there will be at least one benefit to Kelly: he will return a fraction of a second younger than his identical twin, thanks to the effects of time dilation, a principle of Einstein’s theory of special relativity which stipulates that under conditions of great speed time moves more slowly.

According to Universe Today, after six months on the ISS, an astronaut has aged less than people on Earth by about 0.007 seconds.