Who ruled Earth before the dinosaurs? The 'ugliest fossil reptiles'

Loading...

Before the dinosaurs succeeded to the throne, a group of prehistoric reptiles reigned over the Earth.

Pareiasaurs, stocky herbivores that have been called the "ugliest fossil reptiles," are less well-known than their successors. But "they represent the pinnacle of the evolution of vertebrates on land before the dinosaurs," Michael Benton, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Bristol, tells The Christian Science Monitor in an interview.

And understanding more about these animals could provide insight into the world leading up to one of the largest extinctions ever to rock the Earth: the end-Permian mass extinction.

Pareiasaurs roamed the planet for some 10 million years leading up to the extinction event some 252 million years ago. That extinction is thought to have wiped out 90 percent of species living at the time, creating the void that the dinosaurs and many other animals would occupy. Its causes remain a matter of debate. Any insight into pareiasaurs could help scientists better understand that enormous event.

Prehistoric cousins

Fossils of the animal have been unearthed in various regions across the globe including Russia, South Africa, and China. But little has been known about how these different specimens relate to each other.

They're all closely related, Dr. Benton says after further investigating the trove of fossils in China.

"People had thought that maybe the Chinese ones were a special little side branch of evolution. In fact, they're not," Benton says.

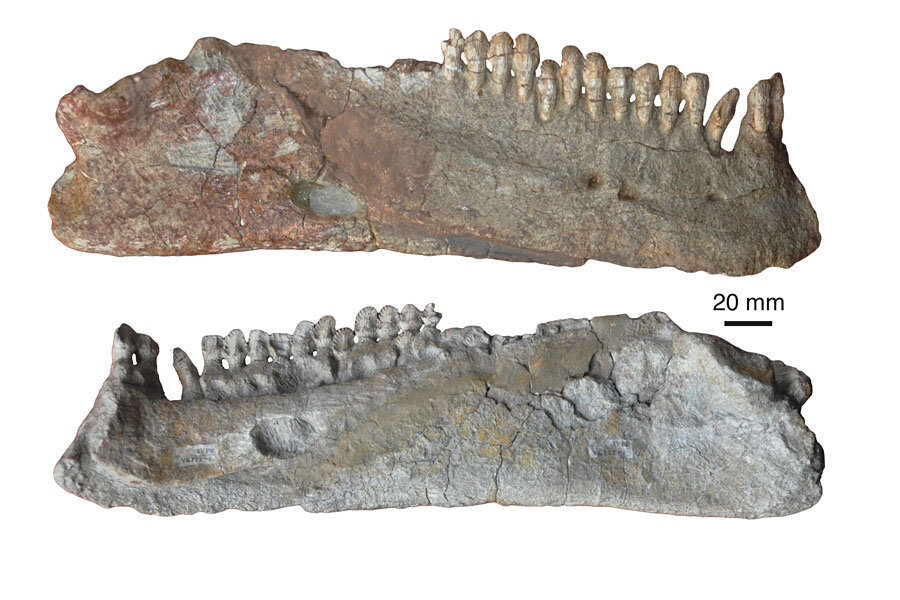

Furthermore, the Chinese specimens were thought to represent six disparate species of pareiasaurs, but Benton's research finds that there were actually just three, according to a paper published Friday in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

"We can use this information as a basis for understanding how pareiasaurs migrated and colonized different parts of the world," Linda Tsuji, curator of natural history at the Royal Ontario Museum who was not part of the study, tells the Monitor in an email.

At the time, the Earth had one single supercontinent: Pangea. So it's not all that surprising that pareiasaur fossils found in present-day China, Russia, and South Africa were close cousins. "Even these large, lumbering creatures, which I'm sure couldn't have moved very fast, were able to stomp around the world," Benton says.

Life in the late Permian

"Despite being important, distinctive (I would be unwilling to call them ugly) members of land ecosystems before the age of dinosaurs, pareiasaurs are relatively poorly understood," Dr. Tsuji says. "This study is critical to our understanding of the evolution of this group."

So what do we know about pareiasaurs?

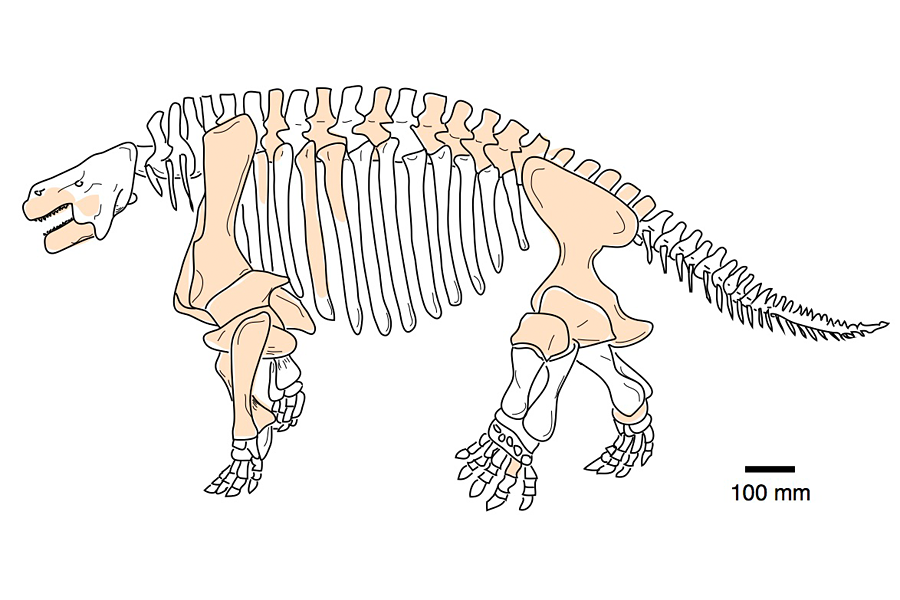

Pareiasaurs were chunky animals, with a thick torso on top of stumpy legs. Their heads were particularly tiny in proportion to their hefty bodies.

Scientists have also described the animals as having strange bumps all over their body, with armored plates in their skin to protect them from falling prey to hungry predators.

Benton likened a pareiasaur to a hippopotamus in size. But the prehistoric animals would have grown up to about 10 feet long. Adult hippos range in length from about 11 to 17 feet.

And, like hippos, pareiasaurs munched on plants.

These herbivorous reptiles likely lived in a similar environment to the modern mammals too. Tropical, wet areas with lots of vegetation would have made for a comfortable life for these top herbivores. And their range was likely quite vast, as most of the Earth would have had such a climate at the time. There were no ice caps in the late Permian.

Death in the late Permian

Pareiasaurs' tenure on this planet was cut short. Ten million years is not a very long time for a species to live in the scheme of life on Earth. "Had the mass extinction at the end of the Permian not happened, they would have very likely carried on lumbering around as perfectly satisfactory, well-armored large herbivores," Benton says.

But all is not lost by such a short reign. Because the animals were dominant in their ecosystems, understanding their success could help scientists determine what caused so many terrestrial and marine animals to disappear.

Was life going along smoothly and then all of a sudden some event happened to wipe everyone out? Or, was the environment deteriorating over a long period of time, slowly driving these animals to extinction?

"The evidence suggests it was a rather sudden event," Benton says. But, "this cleared the world for the dinosaurs."

This massive extinction was a key piece of the evolution of life on Earth. In the time after it, the ancestors of today's animals emerged. The first mammals appeared about 200 million years ago, and dinosaurs ultimately gave rise to birds.