Stellar eclipse plunges distant star system into 3-1/2 years of darkness

Loading...

Think this winter feels long and dreary? In a distant star system nearly 10,000 light years away, every 69 years, the sun disappears in an eclipse that lasts for three and a half years, researchers at Vanderbilt University have discovered.

The newly discovered binary star system, currently known only by the astronomical catalog number TYC 2505-672-1, marks a new record for both the longest stellar eclipse in terms of duration and the longest period between eclipses in a binary system.

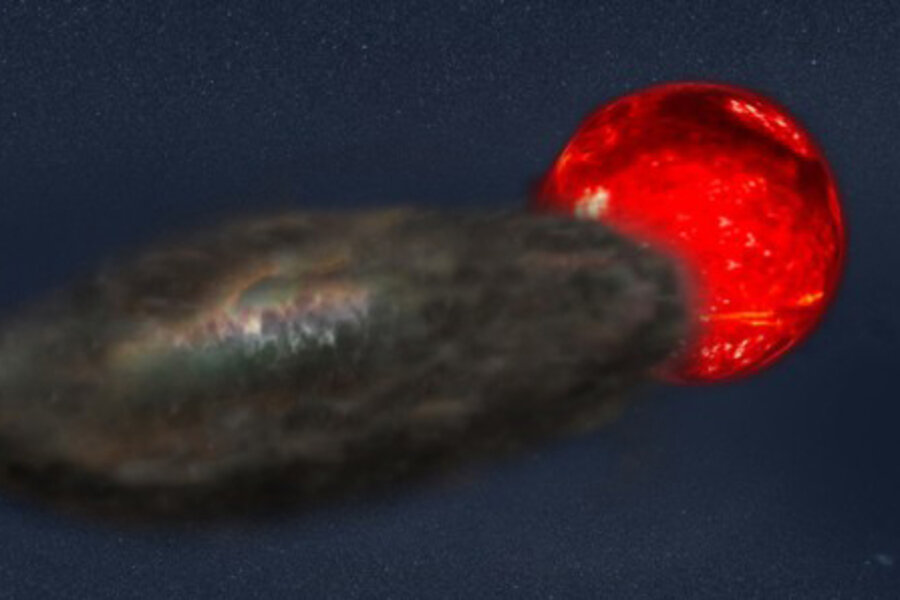

The researchers have found that the system appears to consist of a pair of giant red stars, with one that has been stripped down to a relatively small core and surrounded by a large disk of material that they believe produces the extended eclipse.

“It’s the longest duration stellar eclipse and the longest orbit for an eclipsing binary ever found…by far,” says Joey Rodriguez, a doctoral candidate at Vanderbilt University who led the research, in a news release.

The new discovery, which involved collaboration with astronomers at Harvard University as well as researchers at Las Cumbres Observatory Global Telescope network, a private non-profit, Lehigh, Ohio State, and Pennsylvania State universities, was recently accepted for publication in the Astronomical Journal.

The newly discovered system passes the previous milestone, set by Epsilon Aurigae, a giant star located much closer to Earth, that is eclipsed by its companion star every 27 years for periods that last between 640 and 730 days, or up to two years.

“Epsilon Aurigae is much closer – about 2,200 light years from Earth – and brighter, which has allowed astronomers to study it extensively,” he adds.

The leading explanation for Epsilon Aurigae’s behavior is that the system is made up of a yellow giant star orbited by a normal star slightly bigger than the sun that is embedded in a thick disk of dust and gas oriented nearly edge on when it is viewed on Earth.

The researchers say TYC 2505-672-1, could present a unusual chance to study how planets form over longer astronomical timescales that can outlast a human’s normal lifespan.

“Here we have a rare opportunity to study a phenomenon that plays out over many decades and provides a window into the types of environments around stars that could represent planetary building blocks at the very end of a star system’s life,” said Keivan Stassun, a professor of physics and astronomy at Vanderbilt who co-authored the paper, in the statement.

The researchers were able to learn more about the system by combining observations from two separate networks that drew from nearly a century of photographic plates. Observations by the American Association of Variable Star Observers, a non-profit organization of professional and amateurs who focus on variable stars – or those that change brightness – provided a few hundred observations of the new system’s most recent eclipse.

They then combined this with photographic plates from the long-running Digital Access to a Sky Century @ Harvard (DASCH) program, which includes plates taken by astronomers at the university surveying the northern sky between 1890 and 1989.

Mr. Rodriguez collaborated with Sumin Tang of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics to combine the observations with additional images from the low-cost Kilodegree Extremely Little Telescope, a pair of robotic telescopes that is intended to find exoplanets located around bright stars. KELT’s wide field of view of 26 by 26 degrees led Rodriguez to wonder if its database might also contain recent images of the distant binary system.

The researchers found that while the new system is similar to that of Epsilon Aurigae, the extended disk made of opaque is likely causing the longer eclipse. The new system’s distant location meant that the amount of data they were able to gather from the images is limited, but they estimated that the companion star is about 2,000 degrees Celsius hotter than the sun.

The observation that the star is less than half the diameter of the sun led them to suggest that it may be a red giant with its outer layers stripped away, proposing that the stripped material is what creates the obscuring disk that causes the long eclipse, though they are not fully certain.

But the 69-year duration between eclipses, led the astronomers to calculate that the stars must be orbiting at about 20 astronomical units, a very large distance approximately the distance between our Earth’s sun and Uranus.

But they’re hoping that future technological developments could help confirm their findings.

“Right now even our most powerful telescopes can’t independently resolve the two objects,” Rodriguez says. “Hopefully, technological advances will make that possible by 2080 when the next eclipse occurs.”